In August 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Civil Rights Division, issued a report on their investigation into the Baltimore, Maryland, Police Department (BPD). The report focused on several areas of the police department, and the DOJ summarized the investigation by indicating that the BPD engaged in a

pattern or practice … driven by systemic deficiencies in BPD’s policies, training, supervision, and accountability structures that fail to equip officers with the tools they need to police effectively and within the bounds of the federal law.1

Within the DOJ’s report, the Civil Rights Division’s investigators indicated that BPD’s early intervention program was not effective and attributed the ineffective early intervention system as a factor that may have contributed to police officers’ misconduct and BPD’s failure to identify when officers needed additional training. Also of concern, the report indicated

Related to BPD’s failure to supervise its officers and collect data on their activities, the Department lacks an adequate early intervention system, or EIS, to identify officers based on patterns in their enforcement activities, complaints, and other criteria…

Rather, BPD has an early intervention system in name only; indeed, BPD commanders admitted to us that the Department’s early intervention system is effectively nonfunctional.2

The report went on to two key deficiencies of BPD’s EIS at the time:

- high thresholds of activity for trigger “alerts,” thus delaying notice to supervisors until after egregious misconduct, and

- neglect by BPD supervisors to take appropriate action to correct an officer’s behavior in cases when an alert was triggered.3

The BPD is the eighth largest police department in the United States, and, like many large law enforcement agencies, the BPD has faced challenges with regard to police misconduct. The in-custody death of Freddie Gray in April 2015 was the catalyst for civil unrest in Baltimore, which resulted in dozens of police officers being injured and numerous businesses being damaged and destroyed as a result of the violence. Six Baltimore police officers were arrested but exonerated for the in-custody death of Freddie Gray.4 After an after-action report with regard to the civil unrest was released by the Baltimore City’s Fraternal Order of Police lodge, Baltimore’s police commissioner, Anthony Batts, was fired by Mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.5

Establishing a New Process

The newly-appointed police commissioner, Kevin Davis, had identified the deficiencies within the BPD’s early intervention system long before the DOJ’s report was finalized. He appointed the first director of the Early Intervention Unit and requested the current early intervention process be completely overhauled. Police Commissioner Davis wanted early intervention to be transformed to an effective tool to improve the performance of officers through appropriate training and discipline. Furthermore, the police commissioner wanted to ensure that officers’ supervisors were involved in the initial stages of the process and played a critical role in providing guidance to their subordinates.

One of the first changes was reducing the alert trigger threshold from six complaints to three. Reducing the number of complaints—comprising citizen complaints, incidents of misconduct, excessive force complaints, supervisor complaints, and other incidents—to three allows managers to identify negative behavior patterns early and, subsequently, develop strategies to ensure police officers conduct themselves in alignment with BPD’s policies and procedures.

In addition to appointing a director of the Early Intervention Unit, Police Commissioner Davis also increased the number of personnel assigned to the Early Intervention Unit by adding three experienced police officers, who now directly report to the sergeant of the unit. Also, all of Baltimore Police Department’s command staff received presentations and training on the new process and application of the early intervention system.

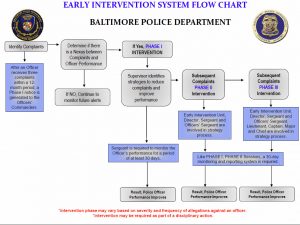

Today, the early intervention system has been transformed to an effective tool, and strict adherence to the following steps are mandated by policy:

- After a police officer receives three complaints within a 12-month period, a Phase One notice is generated to the officer’s commanders. Commanders ensure the officer’s sergeant meets with the officer, examines the alerts, and develops strategies to help the officer improve his or her performance. Furthermore, the sergeant is required to monitor the officer’s performance for a period of at least 30 days following the alert and submit a written report to the Early Intervention Unit, as soon as the monitoring period is completed. If the required report has not been submitted to the Early Intervention Unit, a notice is disseminated to the officer’s commander requiring the commander to have the report submitted immediately.

- Subsequent alerts (trigged by a single complaint after a Phase One intervention) for the same officer would require a Phase Two intervention, which includes not only the officer’s sergeant, but also the director and sergeant of the Early Intervention Unit. During this session, written strategies are discussed and agreed upon by all participants. These strategies could range from recommendations that the officer receive anger management training, referrals to an alcohol treatment program, referrals to domestic counseling for the officer and other family members, training, policy review, or reassignment to another district. The officer’s sergeant is required to further monitor the activities of the officer, determine if the strategies applied are effective, and provide a written report to the Early Intervention Unit.

- A Phase Three intervention includes not only the officer’s sergeant, but also his or her lieutenant, captain, major, and chief. Phase 3 is the final intervention and takes place after an officer has received a Phase One and Phase Two intervention and recommended strategies either failed or were not adhered to. In Phase Three, the intervention involves the officer’s entire command structure, and the officer clearly understands that if improvement is not observed, he or she may face termination. A separate set of strategies are discussed and agreed upon, but in this phase, the officer’s senior supervisors are intimately involved in the process. Phase 3 strategies may be more aggressive than those applied in Phases One or Two. For instance, a supervisor may be required to shadow the officer on all of his calls for service and or review his body-worn camera footage daily. If the complaints are alcohol-related, the officer will have to enter a sobriety program and agree to abstain from consuming alcoholic beverages for one year or face termination. The sergeant is mandated to keep the officer’s entire command updated on a regular basis. During this phase, in addition to other strategies, the possibility of detailing the officer to a new assignment is considered. Like the Phase One and Phase Two sessions, a 30-day monitoring and reporting system is required.

Results of EIS Reform

In 2015, prior to the appointment of Police Commissioner Davis, there were more than 1,000 alerts triggered for complaints received on Baltimore’s police officers. One officer, who amassed more than 100 complaints during his career, received six alerts in 2015, but had only one Phase Two intervention session for the entire year. The Phase Two session did not include the officer’s commander, only his sergeant. In fact, the officer in question had so many complaints that a local news reporter highlighted the officer in a special news report. (This officer was subsequently terminated by Police Commissioner Davis.)

Under the new system, from the beginning of 2016 through October 2016, there were 136 early intervention alerts in the BPD, and 20 Phase Two sessions have been conducted and 2 Phase Three sessions. Phase Two and Phase Three intervention sessions are the most critical because it is an indicator that the initial strategies recommended to the officer in Phase One are not working. It should also be noted that officers are required to participate in Phase Two or Phase Three intervention sessions consistently had a propensity to generate both internal and citizens’ complaints throughout their careers as police officers.

As a result of the new approach to the Baltimore Police Department’s early intervention process, not one officer who has gone through Phase Two or Phase Three, of the intervention process has generated additional complaints. In fact, an officer who was notorious for his accumulation of citizens’ complaints was one of the first police officers to be outfitted with a body-worn camera. During a recent audit of body-worn camera footage, this officer’s footage was reviewed, and it was discovered that this officer’s conduct was not only completely in compliance when he was approached by an irate citizen, but, based on his admirable conduct, the footage will be used in training on how to use de-escalation techniques.

The goal of early intervention is to have officers’ first-line supervisors identify and correct inappropriate conduct when it first occurs. However, in those cases where the BPD’s Early Intervention Unit is involved, the current intervention process has proven to be an effective tool in not only moving the BPD forward, but enhancing the relationship between the community and the police. Although the BPD originally adopted an early intervention system in 2010, the majority of the officers either did not understand what it was or felt that it was a “paper tiger” that had no impact on modifying officers’ behaviors.

Today, the early intervention process is assisting Baltimore’s police supervisors in recognizing problematic behavior early and developing problem-solving solutions to assist police officers in improving their performance. The Early Intervention Unit is housed in the Office of Professional Responsibility, which allows the unit to implement an intervention session as soon as serious complaints, such as those involving use of force, alcohol-related violations, and domestic violence allegations, are reported. The unit has access to several outside professional agencies that the officer can be referred to for immediate assistance, if applicable to the situation. The referral process is confidential and voluntary, and, to date, all officers referred to outside support agencies have participated, which include mental health, anger management, and alcohol treatment programs that specialize in treating police officers, state troopers, and federal agents.

The success of the unit can be attributed to the hard work of the officers assigned to the unit. The sergeant and three detectives assigned to the unit spend countless hours querying BlueTeam (a database where complaints against police officers are maintained) for new complaints that are received on officers. Additionally, the detectives currently assigned to the Early Intervention Unit have worked with or, on many occasions, are familiar with the officers who are selected to participate in the early intervention process. Many times, these detectives can provide a historic perspective on the officers that is not always captured in BlueTeam. For instance, several of the officers who have been identified for interventions have been involved in traumatic events during their careers, such as police-involved shootings, serious injuries in the line of duty, or sustaining injuries during the civil unrest. Some of these officers have not received post-trauma counseling as a result of these events, so the detective’s “inside knowledge” may lead the intervention process to include referral to an outside professional agency.

In conclusion, it should be noted that as a result of the enhanced early intervention system instituted by Police Commissioner Davis, more commanders are referring their officers to the unit for sessions, prior to a complaint being lodged. Additionally, several officers have requested counseling sessions without being directed to do so by their supervisors. Ultimately, the goal is not only to enhance the performance of police officers, but also to provide officers with the necessary support, training, and tools to be successful in their careers. The new approach to early intervention adopted by the BPD is a critical component that will enable the police commissioner to not only comply with the DOJ’s Consent Decree, but enhance the image and productivity of the Baltimore Police Department. ♦

|

Notes:

1 U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department (2016), 134, https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/883366/download.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Kevin Rector, “Charges Dropped, Freddie Gray Case Concludes with Zero Convictions against Officers,” Baltimore Sun, July 27, 2016, http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/freddie-gray/bs-md-ci-miller-pretrial-motions-20160727-story.html.

5 Baltimore City Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge #3, After Action Review: A Review of the Management of the 2015 Baltimore Riots, 2015, http://www.fop3.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/AAR-Final.pdf; Yvonne Wenger, “Baltimore Mayor Rawlings-Blake Fires Police Commissioner Anthony W. Batts,” Baltimore Sun, July 10, 2014, http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/bs-md-ci-batts-fired-20150708-story.html.