Congratulations to the many educators who have begun the shift from the traditional instructor-centered teaching style to a proven practice that acknowledges the experiential and cognitive worth of students, individually and collectively. For instructors and leaders to effect change, they must begin with the outcome-based goal of teaching—to transfer knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs)—which is best accomplished by utilizing the science of how people learn. The instructional concept of the “85 Percent Rule” offers one method for achieving that goal. Simply put, the 85 Percent Rule suggests that an effective facilitator is able to extract 85 percent of the course content directly from the students by asking questions that stimulate deep critical thinking and foster dynamic discussion and reasoning.1

Well-known self-help author Stephen Covey argued that highly effective people “begin with an end in mind.”2 The importance of applying this principle multiplies exponentially as teachers endeavor to shape the masses through their instruction. Therefore, to achieve the true goal of teaching, the transfer of KSAs to the students, instructors would be wise to start at the “end” by first identifying which specific KSAs are to be learned and then applying objectively proven techniques to teach them.

Inexperienced instructors are often caught in the trap of first trying to be entertaining or “covering” a great deal of material in a short time. While both of these goals are valid, and, in fact, desired, the effective teacher focuses primarily on a long-term behavioral shift stemming from the transfer of the KSAs. All other priorities must then be subordinate to this ultimate goal of instruction. This focus on a “mission” is an epiphany for many instructors who may be very entertaining or likable, but are failing to effectively transfer KSAs in a way that allows for the sought-after long-term behavioral shift.

Outcome-Focused Delivery Strategies

It is imperative during the lesson design process to include delivery strategies that are proven to transfer the KSAs through objective testing, even when they may not always be the most entertaining or enjoyable method. Consider the contrast of two search warrant writing instructors: one teaches by telling interesting war stories, reading from his PowerPoint slides, and showing occasional comical video clips. He provides longer breaks and ends class early “to beat traffic.” The second instructor provides students with the tools to “figure it out.” He directs students to write a search warrant and allows student collaboration. The warrants are then evaluated by an attorney who provides feedback. Using this new knowledge, the students complete a second search warrant to engrain the desired behavior. The first instructor is clearly more fun and accommodates passive learners. The second instructor makes the class feel a lot like work, but he was true to the goal—KSAs were transferred and verified.

The mission-centered teaching concept is strictly results oriented, requiring an understanding of how the human brain stores and accesses information. Simply put, the brain stores information away like a file in a cabinet, but each file can be cross-referenced under multiple headings so it can be accessed for diverse reasons. Neural pathways are used to access the memory file. The more pathways there are, and the more they are used (the more often information is accessed), the stronger the memory. These pathways are made even stronger when cognitive reasoning is used to create the new memory file (i.e., self-creating the memory as opposed to hearing someone dictate the information).3 Educators often help students build these stronger pathways via problem-based learning or critical thinking woven into the course curriculum. In the search warrant example, the second class will have created memory files from their behavioral application lesson, so their KSAs will be better retained and can be used with confidence.

The key is to use varied delivery strategies focused on student-created memories to strengthen neural pathways, which allows for higher cognitive functioning. This can be achieved by having the students figure out the course content instead of spoon-feeding them the information. The idea of the “85 Percent Rule” is offered as a guideline to help instructors successfully design a course and teach by facilitation.

Achieving the 85 Percent

An accomplished facilitator should be able to extract 85 percent of the course content directly from the students. Utilizing the collective cognitive resources of students demonstrates the ultimate shift from traditional teacher-centered instruction to learner-centered facilitation, which requires that students demonstrate their knowledge and ability to reason things out. This empowers the students to contribute about 85 percent of the course content. The percentage may vary depending on the complexity of the topic, but 85 percent properly frames the concept. Alan Caddell, an expert in instruction design, explains the facilitative method by simply suggesting that instructors ask the students instead of telling them.4Drawing on existing student expertise is the beginning level of the 85 Percent Rule and is generally achieved by a feigned ignorance by the facilitator to help students engage in focused dialogue, which develops the fullest possible knowledge about the subject. A higher level of learning (transfer of KSA) is present when students think; discuss; debate; evaluate; analyze; and, ultimately, create content through their own thinking and the thinking of those around them. The challenge for instructors is to steer the students to a discovery of course content (the intended KSAs) using well-thought-out and carefully crafted questions.

For basic or refresher course material, students can simply provide the answers collectively. For example, instead of instructors telling students the steps of CPR, they could ask the class to collectively walk them through the steps. This should reveal at least 85 percent of the material, and instructors can augment missing material by using questions to lead the students to develop the answers themselves. For technical topics that go beyond the experience level of the class, additional tactics such as student research and use of “facilitated question mapping” can fill the gap. However it is achieved, it remains incumbent upon the students to solve the questions posed by the instructors. When students generate course content they remember it longer.

Some material is very complex, and the students may not have significant prior knowledge upon which to draw. Therefore, to achieve a deep level of facilitated discussion, the instructor must use carefully crafted questions created during the design process, to stimulate critical thinking and discovery by the students. This process is called “facilitated question mapping,” and, like a map, these questions are designed to take students down a road of discovery that they would not have otherwise found. The questions posed to the class are pre-designed by the instructor to stimulate critical thinking and discussion; in essence, the teacher switches roles with the students. This allows instructors to tap into the deep cognitive reasoning power of the students. Instead of just involving them to get course content, like the CPR example, the students can be guided to actually figure out the solutions. This will more permanently affix the knowledge, skills, and attitudes the course is meant to transfer. A great trick to help one map questions is to place the students in the role of the definitive power (e.g., U.S. Supreme Court justices, when teaching law; chief of police, when teaching policy; creator, when teaching medical topics) and have them reason out the solution. If the instructor can stand back and act as the “pot stirrer” by remaining objectively knowledgeable, he or she can pose questions as a devil’s advocate and serve as a factual source to stimulate deep thought and reasoning.

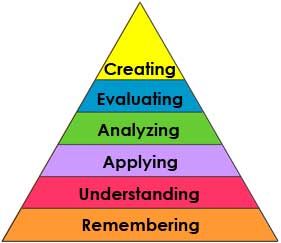

In Bloom’s Taxonomy, a continuum of cognitive learning, one sees a progression of learning or thought that can be mirrored in facilitated questioning. For example, the question “What is the 85 Percent Rule?” asks for a definition for a specific term. To answer that question, the student will simply “define” the rule (Bloom’s Remembering). By contrast, the question, “What are the steps involved in the 85 percent teaching strategy?” asks students to analyze a concept and discuss its component parts (Bloom’s Analysis). An instructor can offer a hypothesized application to help students speculate through questions like “What would happen if you applied the 85 Percent Rule to your own course(s)?” The answers to this would be based on existing knowledge, but would also stimulate critical examination by the students (Bloom’s Evaluating). The next step could be to ask, “How helpful is this strategy, anyway?” This builds on the previous question as the students have thought it through and can now offer a more informed judgment. Finally, students can be guided to “create” (Bloom’s highest level) by answering, “What are other ways to teach instructors to facilitate?”5

Once instructors build the progression of crafted questions (the map) along Bloom’s Taxonomy, they will need to follow up on each thought to bring the students to a deeper understanding. The key is to keep asking questions and not tell students anything that they can discover on their own. If a student asks a question tied to course content, instructors should answer by asking “who can tell me?” or respond by saying “you tell me” or “let’s think that through,” then restating the question or a more elemental foundational question back to the class. The instructor needs to act as a student, in a sense, and be the one to ask questions instead of just giving students the answers. They must approach it as though they don’t know anything about the topic in order to help extract the information from the students. Consider the students as if they were a panel of experts assembled to answer questions, but they are reluctant so everything must be solicited.Facilitated question mapping should be integrated with discovery-filled learning activities. A California police agency demonstrated this in practice when teaching a less-lethal munitions course to police recruits. The mandated topics included agency policy, legality, nomenclature, and deployment tactics. Instead of telling them the course content, the instructor handed out the two types of less-lethal launchers used by the department with inert projectiles and casings to student groups. Each group was asked to examine, dry-fire, break-down, and manipulate each launcher and the munitions. The groups were directed to collaborate and determine how these weapons worked and how they should be carried and deployed in the field. In addition, they were instructed to create a department policy that would govern the use of the launchers. Even though they lacked experience, police recruits were able to cover over 85 percent of the course content completely on their own. Moreover, the students likely had much higher levels of retention and enhanced ability to apply the knowledge because they “figured it out.” In essence, they developed the agency policy, rather than having memorized it. When students became stuck in the process, the instructor used previously created facilitated question mapping to lead the students in self-discovery.6

Although often the preferred method in the past, it has been shown that lecturing may not be the most effective way of transferring KSAs. It is now known that the collective knowledge and reasoning power of the students can be used to generate most, and sometimes all, of the course material. When instructors remain true to the goal of teaching and utilize the science of how people learn, they can extract the course material from the students by integrating activities with well-crafted critical thinking questions in the framework of the 85 Percent Rule. This elevates students into the highest levels of learning and fosters a rewarding feeling of a job well done for instructors.

Instructor development courses offered by the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, as well as courses in many other areas, have been teaching law enforcement instructors critical thinking and classroom facilitation for many years. Those efforts have resulted in better academy and advanced courses that are student-centered and outcome-based. ♦

| Kris Allshouse serves as Executive Director for the Los Angeles County Regional Training Center, a non-profit created to train public agencies. Kris is a retired Police Sergeant and California POST Master Instructor. He has designed and taught over 40 courses for California Law Enforcement including the POST ICI Officer Involved Shooting, Homicide, Burglary, Vehicle Theft, and Identity Theft Courses. Kris was an instructor and curriculum writer for the POST ICI Instructor’s Course, the IDI Leadership Mentoring and Coaching Course, the IDI Advanced Instructor Course, and the Master Instructor Certification Course. |

Notes:

1The 85 Percent (85%) Rule concept was created by and is copyrighted by Kris Allshouse.

2Stephen Covey, 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change, 25th Anniversary Ed., (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2013).

3Gene Van Tassell, “Neural Pathway Development,” Brains.org, 2010, http://www.brains.org/path.htm (accessed March 24, 2015).

4 Alan Caddell, interview by author, January 23, 2013.

5Benjamin S. Bloom, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (New York: Longmans, Green, 1956).

6Richard Paul, “The State of Critical Thinking,” The Critical Thinking Community, 2004, http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/the-state-of-critical-thinking-today/523 (accessed March 24, 2015).

Please cite as

Kris Allshouse, “The 85 Percent Rule: Effective Outcome-Based Instruction,” The Police Chief 82 (April 2015): web only.