Human trafficking is a complicated issue, addressed via international treaty as well as national or state law. Despite differing national identities and values, U.S. and Austrian law enforcement both seek to address this public health issue and transnational crime with victim-centric approaches and evolving law enforcement methods. A comparative analysis of the prevalence, legal aspects, approaches, and methods used in both countries can help expand the successful approaches and methods while refining the less than advantageous processes and procedures.

Anti-Trafficking Laws in Austria

The most important Austrian criminal law provision concerning human trafficking is the offense of § 104a of the Austrian Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch, StGB), which is entitled “Menschenhandel” (meaning “human trafficking”).1 This provision was created in 2004 in implementation of Austria’s international obligations and has changed little since then.2

According to § 104a StGB, any person who recruits, accommodates, or otherwise receives transports, transfers, or offers to another an adult person by illegitimate means with the intention of exploitation is liable to imprisonment for six months to five years. These illegitimate means include the use of force or dangerous threats, deception about material facts, abuse of a position of power or of a situation of duress, mental impairment or vulnerability, intimidation, or the giving or receiving of benefits for transferring the control over the person. The exploitation that has to be intended includes sexual exploitation, exploitation by removal of organs, labor exploitation, and exploitation for the purpose of begging or for the purpose of committing offenses. In addition, § 104a(4) StGB provides for a higher penalty (i.e., imprisonment for one to ten years) for any person who commits the offense in connection with a criminal association, by use of serious violence, in a way which intentionally or grossly negligently places the life of the other person at risk, or by causing a particularly serious detriment for the victim. This very same penalty also applies if the victim of the human trafficking is a person under the age of 18 (§ 104a(5) StGB); in these cases, however, criminal liability does not require the use of illegal means as defined above.3

Under Austrian law, however, a number of other offenses may also be applicable in cases of human trafficking. The first offense to think of is the so-called Grenzueberschreitender Prostitutionshandel (cross-border prostitution trade). According to § 217 StGB, any person who procures or recruits another for prostitution in a country different either from the country of which the other person is a national or the country of which the other person is a habitual resident, is liable to imprisonment for six months to five years (or for one to ten years if the offense is committed commercially). This even applies if the other person already engages in prostitution. In contrast to § 104a StGB (concerning adults), criminal liability under § 217 StGB requires neither illegitimate means nor an intent to exploit. § 217 StGB therefore results in a quite extensive criminal liability and is repeatedly subject to criticism.4 However, § 217(2) StGB, which provides for a higher penalty, refers to means that are similar to the ones described as illegitimate in § 104a StGB. In cases where these illegitimate means and intent to exploit overlap, § 217 even absorbs the basic offense under § 104a(1) for adults.

In addition, crimes such as the exploitation of an alien (Ausbeutung eines Fremden, § 116 of the Austrian Aliens’ Police Act (Fremdenpolizeigesetz, FPG) or human smuggling (Schlepperei, § 114 FPG) may also cause criminal liability under Austrian laws in cases of human trafficking—apart from various “ordinary” offenses such as dangerous threats, (aggravated) assault, sexual abuse, rape, or coercion.

“The United States appears to be somewhat ahead, having already implemented measures that are still in planning or early implementation stages in Austria”

According to § 12 StGB, however, the crimes described above are also committed by anyone who either intentionally incites another person to commit such crimes, facilitates these crimes, or contributes to the commission of such crimes by another. Furthermore, it is also punishable under Austrian criminal law if these crimes are merely attempted but not completed successfully (§ 15 StGB).

Regarding survivors of human trafficking, it is important to mention they are often subjected to violence, serious threats, violations of their sexual integrity and self-determination, or the exploitation of their personal dependency. Therefore, Austrian law entitles such survivors to psychosocial and legal support throughout the legal process, as well as extended victims’ rights in criminal proceedings, such as being interviewed by a person of the same gender and more considerate questioning modalities (taking into account, e.g., the possible traumatization of the survivors), as well as exclusion of the public during the main trial. There are also special regulations for granting foreign survivors a special residence permit for protection (§ 57 Asylum Act [Asylgesetz]).5

Furthermore, the non-punishment principle, which derives from international and European legal frameworks, also applies to the Austrian criminal procedure.6 In Austria, it is currently assumed that the non-punishment principle is covered by the provisions on Entschuldigender Notstand (Emergency; § 10 StGB). This allows for case-by-case assessments to excuse offenses committed by survivors, rendering them non-punishable.

New Jersey and U.S. Federal Anti-trafficking Laws

In New Jersey, human trafficking is a crime defined statute (N.J.S.A. 2C:13-8 et al.) making it illegal to force someone to engage in sexual activity or to provide labor or services. The law does not require physical force or threats and considers other forms of coercion such as controlling identity documents or access to controlled dangerous substances (drugs). A person can also be guilty of human trafficking if they receive anything of value for overseeing the human trafficking or if they contribute to a minor engaging in prostitution with or without coercion. For this, the sentence is a minimum of 20 years in prison without parole and can go as high as life without parole.

Someone who facilitates human trafficking but is not a leader or who tries to procure the victim for another to traffic is also guilty of a crime.7 For this, the sentence is a minimum of five years in prison with a period of parole ineligibility. However, humanitarian or charitable aid provided directly to the victims of human trafficking are explicitly exempt, even if it is known the aid will further human trafficking. This way, victims can still receive necessary help even if they are not ready or able to remove themselves from the trafficking situation.

Victims of human trafficking who commit crimes because of being trafficked, including the crime of human trafficking itself, can raise an affirmative defense that their actions were a direct result of being a victim.8 They are also entitled to have their entire criminal history expunged or sealed and have additional civil remedies available to them.9 The idea is to acknowledge how some victims become a part of a human trafficking organization and commit crimes therein in order to survive, and had they not been so victimized by that point, they never would have committed those crimes The victim must raise the defense, and must prove it. The downside is the affirmative defense risks deepening the trauma suffered by the victim, but that is being balanced against the need to protect against true human traffickers who may simply claim victimhood to avoid consequences.

“A human rights-based approach is at the core of the plan, placing affected individuals and their rights at the center of government action”

At the U.S. federal level, provisions against human trafficking gain their impetus from the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude (except as criminal punishment). It is further codified by law, where it is separated into sex trafficking and forced labor. The laws—18 U.S.C. § 1581 et sec.—are very similar to those of New Jersey and require some form of coercion or force to control the victim. The laws address commercial sex acts of adults and minors (under 18), as well as forced labor. At present, victims of human trafficking are eligible to apply for temporary immigration visas, either as victims of trafficking (T-visa) or of violent crime (U-visa).

There are notable differences between U.S. federal and state laws. Under U.S. federal law, the sexual activity must be commercial, requiring something of value being given or received.10 New Jersey law simply requires forced sexual activity, so a trafficker forcing a victim to engage in sexual activity with another individual for “training” purposes, where nothing of value is exchanged, is a state crime in New Jersey, but it does not meet the prerequisite of a U.S. federal crime. The facilitation of access to drugs is codified as a form of control in New Jersey, which takes into consideration the way some traffickers will use substance abuse issues to manipulate victims without the use of physical force or restraints. Under U.S. Code, the “abuse or threatened abuse of law or legal process” is considered a form of coercion, which encompasses threats of immigration consequences as well as threats of criminal and other charges.11 While such threats could still be considered forms of coercion under New Jersey law, the concept is explicitly codified under federal law.

Human Trafficking Prevalence in the United States and Austria

While human trafficking affects millions of people around the world, reliable prevalence information is still difficult to obtain. A lack of uniform data collection methods, differences in definitions, inconsistent victim identification tools, and victims’ hesitancy to report their experiences to the police makes human trafficking data challenging to collect and analyze. Human trafficking is also a very complex crime with distinct forms of exploitation that require in-depth analysis to get a clear understanding of who becomes a victim and why. These issues lead to great discrepancies in prevalence estimates based on which entity collects the information (for example, criminal justice agencies or service providers) and variations in trafficking legislation and cultural norms across countries.

Prevalence in Austria

Austria is a destination and transit country for men, women, and children trafficked for sexual exploitation, labor exploitation, forced begging, and forced criminality. Data tracking occurs predominantly through the Criminal Intelligence Service Austria and Statistik Austria—Austria’s national statistical system, responsible for the vast majority of European and federal statistics produced within Austria.

The data from Criminal Intelligence Service Austria reflect cases of human trafficking reported to the police, which stand in contrast to many unreported activities. Willingness to cooperate with law enforcement is low, as many of these crimes occur in Austria’s red-light districts or victims choose not to involve police due to their illegal employment and residence status.12

Statistik Austria data, on the other hand, rely on data from three nonprofit organizations that work with different groups of victims of trafficking: LEFOE-IBF (Intervention Centre for Trafficked Women);13 MEN VIA (assistance for male trafficking victims);14 and Drehscheibe Wien (service of the city of Vienna for unaccompanied foreign minors, e.g., refugees, but also victims of trafficking).15 Statistik Austria’s data on Human Trafficking are reported to EuroStat.16

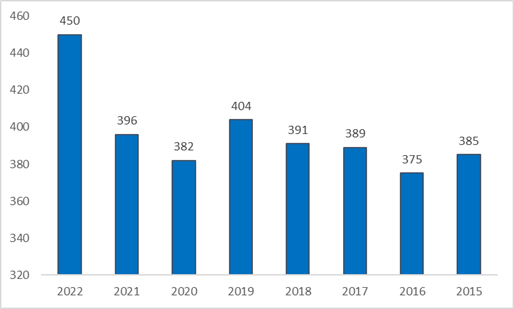

Data collected on law enforcement actions are based on § 104a StGB (Menschenhandel—human trafficking) and § 217 StGB (Grenzüberschreitender Prostitutionshandel—cross-border prostitution trade) and are published annually in the Situation Report Human Smuggling and Human Trafficking (Lagebericht Schlepperei und Menschenhandel).17

Table 1. Completed investigations (moved to prosecution)

|

|

2023 |

2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2017 |

2015 |

2014 |

|

§ 104a StGB |

24 |

41 |

28 |

41 |

42 |

34 |

56 |

61 |

|

§ 217 StGB |

13 |

15 |

20 |

14 |

22 |

23 |

42 |

38 |

Table 2. Investigated suspected traffickers by gender

|

|

2023 |

2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2017 |

2015 |

2014 |

|

Male |

47 |

49 |

38 |

58 |

62 |

66 |

74 |

61 |

|

Female |

13 |

21 |

31 |

32 |

43 |

75 |

58 |

38 |

Table 3. Victims identified by police

|

|

2023 |

2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2017 |

2015 |

2014 |

|

Number of identified victims |

||||||||

|

§ 104a StGB |

42 |

104 |

75 |

66 |

66 |

61 |

62 |

45 |

|

§ 217 StGB |

17 |

26 |

44 |

23 |

53 |

60 |

57 |

29 |

|

Victim origin |

||||||||

|

Austria |

0% |

— |

8% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

1% |

|

EU member states |

47% |

27%** |

79% |

39% |

51% |

50% |

87% |

99% |

|

Other/unknown |

53% |

73% |

13% |

61% |

49% |

50% |

13% |

|

|

Minor victims (§ 104a & 217) |

||||||||

|

Minor victims |

1 |

9 |

6 |

10 |

14 |

6 |

—* |

5 |

*no information available

** includes Austrian citizens (number unreported)

Table 4. Forms of exploitation (by no. of cases)

|

|

2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2017 |

2015 |

|

Sexual |

17 |

13 |

21 |

25 |

24 |

41 |

|

Labor |

20 |

8 |

15 |

8 |

3 |

9 |

|

Forced Begging |

1 |

6 |

1 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

|

Forced Criminality |

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Child trafficking |

3** |

1** |

2* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

42 |

28 |

41 |

42 |

34 |

56 |

* 2 cases of forced marriage

** unknown circumstance

Compared to the official police statistics through the Criminal Intelligence Service, case numbers reported to nonprofit service providers are significantly higher.

It should be noted that nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) do not distinguish between identified or presumed victims, as they offer unconditional assistance. Double counting of victims between police, prosecution, and NGOs cannot be avoided, while double counts between different NGOs are less likely because they generally focus their efforts on different victim groups (men/women/children).

Prevalence in the United States

Human trafficking is known to occur within New Jersey and throughout the other U.S. states and territories. Data tracking of the prevalence is limited for various reasons, some of which were previously mentioned.

One obstacle that exists with reported cases of human trafficking in the United States is the reporting process itself. In some places, such as New Jersey, law enforcement are required to report human trafficking cases to an agency, but there are no publications or databases for the collected data—if the data are in fact properly reported every time, as mandated. At the federal level, there is no requirement to report to any agency or database.

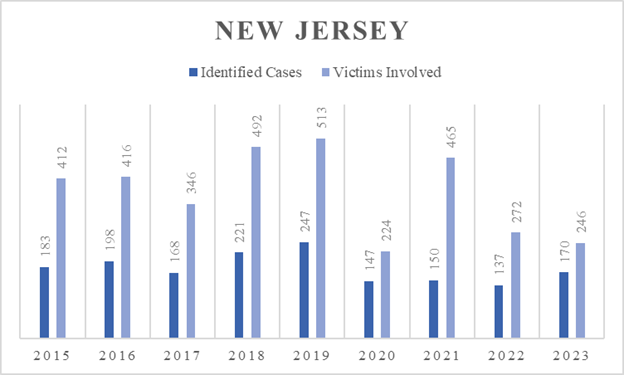

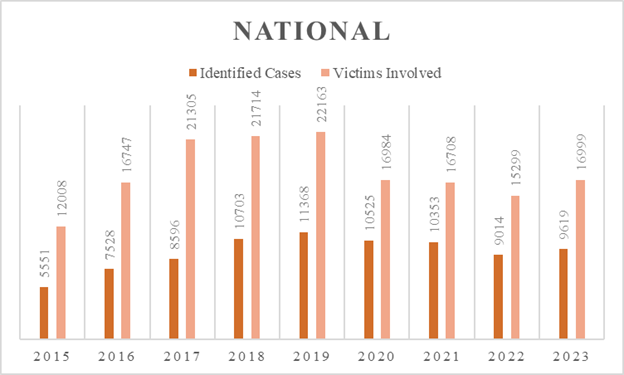

Despite these difficulties with tracking human trafficking cases, there are some data to show the pervasiveness of human trafficking within New Jersey and the United States as a whole. These data come from the National Human Trafficking Hotline, operated by Polaris, a nonprofit focused on ending human trafficking.18 Their information is based on contacts with the hotline–telephone calls, texts, website contacts, etc., and from there, they track the number of cases identified as well as victims involved in the cases. They also collect and share some data for types of trafficking, sex of victims, and whether they were adults or minors. Notably, not all cases are accounted for in the subdivided categories, and the data are clearly incomplete. Additionally, U.S. territories often show no cases of human trafficking over the years, and while it is possible they do not have any instances of trafficking, it is more likely that it simply goes unreported to the hotline. Nevertheless, data from the hotline are the best statistical guide to show the prevalence of human trafficking in different states—such as New Jersey—and the United States as a whole.

Looking at the reported data, New Jersey averaged around 1.5–2.0 percent of the national human trafficking cases, despite having approximately 2.7–2.8 percent of the national population. Of the identified and further distinguished cases from New Jersey over the years, more than 50 percent of the human trafficking involved sex cases, compared to the national data, which lists approximately 85 percent of the known cases involved sex trafficking. Regarding the sex of victims—listed by the Hotline as either male or female—both New Jersey and the United States as a whole have more than 80 percent female victims. Finally, New Jersey has a higher number of minor or underage victims than the national average, with 25–40 percent compared to approximately 30 percent at the national level.

Law Enforcement Approaches in Austria

The Austrian federal government established a task force to combat human trafficking over 20 years ago. Its primary goal is to strengthen and coordinate Austria’s measures. It is composed of representatives from federal ministries and government agencies, the federal provinces, social partners, and specialized NGOs, such as the IBF, the Men’s Health Center, or ECPAT.19

One of the main tasks of this task force is the development of a National Action Plan (NAP), with the seventh National Action Plan currently being implemented. For the first time, this plan covers a four-year period (2024–2027). At the end of each National Action Plan’s term, the task force submits a report to the federal government and parliament. In addition to these final reports, annual interim reports are provided.20 The NAP includes measures for international and national coordination, prevention, victim protection, prosecution, and monitoring. A human rights-based approach is at the core of the plan, placing affected individuals and their rights at the center of government action. Specific requirements related to potential dependencies of children, asylum seekers, and persons with disabilities are also taken into account.21

The currently implemented NAP organizes 103 measures into five chapters, each outlining specific actions, timelines, responsibilities, and indicators for measuring implementation. Chapter 1 includes measures for national and international coordination and cooperation. These encompass annual conferences with federal provinces, working groups with representatives of social partners, and extensive annual meetings at the Ministry of Justice with victim protection organizations, the judiciary, and public prosecutors to develop best practices. Additionally, it aims at strengthening international exchange and supporting relevant international projects.22

Chapter 2 determines public awareness measures, such as school events focused on online safety and the prevention of child trafficking, as well as media sensitization initiatives. It also aims to strengthen the human trafficking hotline of the Federal Criminal Police Office, which operates 24/7 to receive reports from the public.23 Training programs are provided for police officers, refugee support staff, interpreters, officials at the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum involved in international projects (e.g., UNHCR), judges, prosecutors, and health care professionals. Additionally, the plan seeks to raise awareness within particularly affected private-sector industries, such as agriculture, domestic care, and construction. Actions are also being taken to strengthen the legal framework, including projects addressing labor exploitation in supply chains.24

Chapter 3 aims to improve the early identification of victims through various measures, including the development of indicators and informational materials. It also includes initiatives to strengthen victim protection services and improve social reintegration measures, such as qualification programs offered by the Public Employment Service. Additionally, the task force seeks to improve compensation for victims.25 Interestingly, the inclusion of survivors also is being institutionalized in the current NAP—an approach that is relatively new for Austria compared to U.S. approaches.26

Chapter 4 outlines actions to enhance law enforcement measures, including the development of practical guidelines for implementing the non-punishment principle, the review of legal frameworks, and the strengthening of cooperation between law enforcement agencies and NGOs.27

Additionally, in Chapter 5, the task force commits to comprehensive monitoring and the promotion of research and education on current issues related to human trafficking. This includes fostering research coordination and increasing the visibility of research findings.28

With the NAP, the Austrian government commits to a comprehensive approach that actively engages law enforcement agencies, the judiciary, the media, health care agencies, private businesses, and the general public.

Law Enforcement Approaches in the United States

The approach to human trafficking in the United States is collaborative and victim centered. Law enforcement, government, and nongovernmental agencies work together at both the state and federal levels.

In New Jersey, law enforcement personnel learn about human trafficking in the police academy, where they study how to identify human trafficking crimes and practice interactions with potential victims of human trafficking. From there, every county is required to have a designated detective/investigator and assistant prosecutor to serve as human trafficking liaisons and are required to investigate whenever human trafficking is suspected. The liaisons must then report the trafficking case to the state’s Division of Criminal Justice, and all legally significant events—charging, arrests, case disposition, etc.—must be reported as well.

New Jersey laws require certain staff of hotels and health care facilities to attend a one-time training on human trafficking.29 There is no requirement for ongoing training, but the course content must be reviewed at least every two years and always be available. Judges and judicial personnel have access to a course on human trafficking that covers the needs to respect and restore the rights of victims, but attendance is not mandated by law.

A hotline exists for anyone to report suspected human trafficking, but there is no mandate or requirement for anyone to do so. While law enforcement is required to investigate if they suspect human trafficking, this is the same obligation they face with any other crime. However, child abuse in any form must be reported to the state department for child protective services if suspected by certain caretakers, such as teachers. This does encompass suspected human trafficking of a minor (under 18) but also includes suspected neglect or other forms of child abuse.

On a U.S. federal level, according to the FBI, “victim recovery is the primary goal of trafficking investigations.”30 It is only after that they will look to arrest and prosecute the traffickers themselves. Like New Jersey, they take a multidisciplinary approach and law enforcement collaborates with other community organizations to aid and support victims and has a hotline where anyone can report suspected human trafficking. Unlike New Jersey, the initial focus is solely on the victim and not on helping the victim and investigating the trafficker at the same time.

Like New Jersey, there is no legal requirement for anyone to report suspected human trafficking. Health care providers are required to report suspected child abuse for any minors (under 18) if encountered while working as a federal employee or in a federal facility. However, there are no laws requiring health care workers or others to report suspected human trafficking of anyone over the age of 18.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both the United States and Austria seek to address human trafficking despite its particularly challenging characteristics. Although their general approaches to crime may differ, which is reflected in substantial disparities in statutory sentencing ranges, both countries acknowledge the necessity of victim-centered approaches to combat human trafficking. These approaches take into account the complex realities of survivors’ lives, in which individuals may simultaneously or subsequently become perpetrators of crimes. This recognition is reflected, for instance, in provisions that allow for exemptions from punishment under certain circumstances, as well as in special immigration measures, such as the granting of temporary visas.

In terms of law enforcement, the United States appears to be somewhat ahead, having already implemented measures that are still in planning or early implementation stages in Austria, such as the active involvement of survivors in anti-human trafficking efforts or mandatory training within the health care and tourism sectors. during proceedings, which they are entitled to by law.

Regarding prevalence data, clearly data collection poses significant challenges in both countries, which have yet to be properly resolved.

Academic collaborations, such as the one that led to this paper between the University of Graz (Austria), Montclair State University (New Jersey), and the Atlantic County Prosecutor’s Office (New Jersey), which brings together professionals and survivors and is characterized by the exchange of students and faculty, can offer valuable contributions to addressing this global issue by fostering mutual learning and the development of best practices. d

Notes:

1For an English translation of the whole Austrian Strafgesetzbuch, see Andreas Schloenhardt, Frank Hoepfel and Johannes Eder, eds., Strafgesetzbuch/Austrian Criminal Code, 2nd ed. (Vienna: NWV, 2021).

2UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, Res. A/RES/55/2, UN Treaty Series 2237 (2000), 319; Doc. A/55/383; Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Res. A/RES/54/23, UN Treaty Series 2171 (2000), 227; Council of the European Union Framework Decision on combating trafficking in human beings (2002/629/JHA), OJEC 2002 L 203/1 (meanwhile replaced by the Directive 2011/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA, OJEU 2011 L 101/1 as in the applicable version); Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, Austrian Federal Law Gazette (Bundesgesetzblatt) III, No. 2008/10.

3For more details see Klaus Schweighofer, “§ 104a StGB,” Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch, 2nd ed. (2016) with further references.

4See Thomas Philipp, “§ 217 StGB,” Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch, 2nd ed. (2020), margin note 6 with further references.

5For an overview on survivor’s rights see, e.g., Barbara Steiner et al., Gemeinsam Gegen Menschenhandel Kompaktwissen Für Die Praxis: Strafverfahren, Entschädigung, 29; Sebastian Gölly, “Die Stellung des Opfers im Strafverfahren,” in Gewaltschutzrecht samt Cybermobbing, Strafrecht und Familienrecht, eds. Astrid Deixler-Hübner/Mariella Mayrhofer (2023), 229.

6 Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings, Article 26; and EU Directive 2011/36/EU on Combating Human Trafficking, Article 8.

7New Jersey Revised Statutes Title 2C – The New Jersey Code of Criminal Justice, § 2C:13-9—Second Degree Crime; penalties (2024).

8New Jersey Revised Statutes Title 2C – The New Jersey Code of Criminal Justice, § 2C:13-8—Human Trafficking (2024).

9New Jersey Revised Statutes Title 2C – The New Jersey Code of Criminal Justice, § 2C C:44-1.1—Certain Convictions Vacated, Expunged (2024); New Jersey Revised Statutes Title 2C – The New Jersey Code of Criminal Justice, § 2C:13-8.1—Civil Action Permitted by Injured Person (2024).

10Sex Trafficking of Children of by Force, Fraud, or Coercion, 18 U.S. Code § 1591(a).

11Sex Trafficking of Children of by Force, Fraud, or Coercion, 18 U.S. Code § 1591(e).

12Criminal Intelligence Service Austria, Types of Crime and Investigations: Trafficking in Human Beings (2025).

13 LEFÖ, IBF – Intervention Center for Trafficked Women.

14MEN Via – Opferschutz für Männer, die von Menschenhandel Betroffen Sind, 2024; MEN Männergesundheitszentrum, 2024.

15“Ueberblick ueber Angebote fuer Kinder, Jugendliche Und Familien in Wien,” Stadt Wien.

16Riegler Romana, email message to Daniela Peterka-Benton, January 27, 2025.

17“Lageberichte,” Bundeskriminalamt, updated August 1, 2024.

18“National,” U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline by Polaris.

19Support for men as victims of human trafficking, see https://men-center.at/englisch; National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking (2024), 6; ECPAT Austria, Working Group for the Protection of Children’s Rights against Sexual Exploitation.

20Federal Ministry of European and International Affairs, Austria, “Combating Trafficking in Human Beings.”

21National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 6.

22National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 13–18.

23Federal Ministry of the Interior, Criminal Intelligence Service Austria. In the year 2022, 750 reports were registered through the hotline, see Federal Ministry of the Interior, Annual Report Trafficking in Human Beings 2022 (2023), 30.

24National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 24.

25National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 25-34.

26National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 29.

27National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 34.

28National Action Plan on Combating Human Trafficking, 35–39.

29NJ Admin. Code § 5:10-29.1

30Federal Bureau of Investigation, “FBI Newark Raises Awareness about the Threat of Human Trafficking,” news release, 2024.

Please cite as

Kieran Barrett et al., “Transatlantic Approaches to Human Trafficking: A Comparative Study of Austria and the United States,” Police Chief Online, September 17, 2025.