Photo by Portland Oregon Police Bureau

“A community is like a ship; everyone ought to be prepared to take the helm.”—Henrik Ibsen, playwright

“It’s one thing to be part of an organization. It’s another thing to be part of the community.”—Travis Kelce, professional football player

Rarely do the names of famous 19th-century Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen and longtime National Football League All-Pro tight end Travis Kelce come up in the same conversation. However, despite their wildly different backgrounds, both offer thought-provoking insights about the nature of community.

“Community policing is a philosophy that promotes organizational strategies that support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder, and fear of crime.”1

Similarly, while police agencies across the world practice community policing in different ways, each department—regardless of its size, location, or community—has valuable insights to share and lessons to learn from its unique approach and experiences.

In all facets of policing, translating academic theory into operational practice is easier said than done. This is especially true regarding community policing (CP) and community engagement (CE), which are long-running significant challenges for police departments and executives.

Community and Police in Tandem

For many decades, the Portland, Oregon, Police Bureau (PPB) has developed a diverse community advisory group structure to address safety concerns and collaborate on specific police issues, such as bias-driven crimes, gun violence, crime victims’ rights, and police responses to calls involving individuals experiencing or believed to be experiencing mental health crises.

Over time, Portland community members from diverse backgrounds, including Slavic, African American, Asian Pacific Islander American, Muslim, and Latino communities; faith-based groups; and business enterprises, have volunteered their time, expertise, and passion for justice and safety. They have collaborated with the Chief’s Office to address specific crime issues, police training, and policy development, with a focus on building trust, increasing public confidence in police responses, and enhancing community service. Although PPB considers itself a champion of CP, these CE structures primarily operated in silos until recently, with community member access to PPB personnel essentially limited to police leadership.

In 2020, PPB’s community-led advisory groups came together in an alliance—the Coalition of Advisory Groups (CAG)— to work as a unified body representing different community sectors eager to work with the chief of police on public safety issues.2

Initially, the CAG regularly met with the police executive team and, during noncrisis times, discussed a wide range of policing-related issues, including police staffing shortages, hiring, and recruitment programs.

However, it soon became clear that this approach to CE did little to resolve the persistent question of how to expand community members’ access to the PPB rank-and-file sworn members. The PPB Office of Community Engagement (OCE), established in 2017, quickly recognized the importance of addressing this issue, as strong community support is essential for any police department to carry out its patrol and investigative missions effectively.

As a result, OCE began to incorporate officers from the Training Division, Bias Crime Detective Unit, and Patrol Sector into the CAG structure. These designated officers began attending advisory group meetings, leading safety workshops, and serving as links to the police bureau. For their part, advisory groups began to expand their own outreach to include additional officers.

Community Engagement + Problem-Oriented Policing Model

Modern CE strategies are complex and multidimensional. Therefore, they must be understood at an organizational level and broadly defined to meet the constantly changing needs of police services and the evolving societal expectations of policing.

Officer participation in community events, such as gatherings, coffee with a cop, sports, cultural festivals, youth camps, and similar activities, is a crucial part of many departmental CE strategies. While these interactions are valuable—and often requested by community members—they typically start and end with that single contact.

Police managers should view these events as opportunities—initial steps toward building and sustaining long-term community-police partnerships. In the words of Ben Bradford, director of the Centre for Global City Policing at University College London, “Trust and confidence are about more than visibility—it’s about presence and engagement.”3

An important question for such opportunities is, “What ongoing relationships are being built from any particular CE event?” One-time contacts without ongoing relationships can still support a meaningful overall CE strategy. However, in today’s environment of viral videos, anti-police discussions, and limited staffing, most agencies need to be very intentional with their CE efforts to maximize their impact.

Partnerships with the community are crucial for effective and comprehensive policing, especially because the community and business sectors are key sources of talent and culturally aware individuals. Active engagement and integration of these valuable resources into overall mission plans can only enhance police responses and strategies.

Often, despite the best intentions, CE programs fail to answer a crucial question: Are these efforts enhancing the department’s overall strategy to prevent and reduce crime and the fear of crime?

CP alone is unlikely to prevent crime or build public trust in law enforcement. However, when combined with a targeted problem-oriented policing plan, CP strategies can help identify key community stakeholders to involve in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary effort to address crime and the fear of crime. This approach can improve confidence in the police, increase engagement with the justice system, and foster greater involvement and ownership among victims and witnesses as they navigate the complex criminal justice process.4

Community Policing Case Study

The following community engagement strategy presents a more effective model of CE and problem-oriented policing, focusing on enhancing the overall organizational mission of PPB:

“Transforming the dynamic between the police and the people we serve”

“Reducing crime and the fear of crime”5

It’s common to see elderly community members fishing on the Willamette River in downtown Portland. In April 2024, an older immigrant man who lived in a downtown apartment building that housed many other elderly immigrants was fishing when he fell victim to a violent, unprovoked attack perpetrated by an unknown suspect.6

The victim’s family and the broader Portland immigrant community were deeply shocked by the assault, and many elderly community members were afraid to leave their homes. PPB Bias Crime detectives opened an investigation and worked with the public to identify the assailant(s). Eventually, the suspect was identified and arrested.

This tragic incident highlights how “fear of crime” significantly affects the community, distorting their sense of safety and complicating daily routines, such as walking to the park; shopping for groceries; and, in this case, fishing at the river.

In response to the attack, the Chief’s Office held a series of community listening sessions, met with the victim’s family and leaders of the immigrant community, and acknowledged the profound impact of bias crime incidents. Such engagement inspired many community members to work with police investigators to identify the perpetrator, demonstrating a willingness to take responsibility for community safety and serve as valuable partners to the police.

In addition to the listening sessions, the PPB Bias Crime command developed a community safety workshop and engaged with numerous immigrant groups, many of which to that point had experienced little or no positive interactions with the police.

Despite the tragic nature of the incident, it nonetheless served as a catalyst that resulted in an ongoing partnership with a community sector that had not previously worked with the police. Such partnerships are the natural outcome of PPB’s intentional strategy to build trust and minimize cultural and linguistic challenges. Due to this strategy, the Bias Crime Unit can now conduct investigations more effectively and draw on support from the community.

While bias crimes occur less frequently than traffic crashes, crimes involving guns, and many other incidents resulting in police responses, the impact—both psychological and emotional—of bias crimes on the community’s identity, perception of being targeted, and fear is such that it requires a strategic engagement approach. Additionally, the chief and his executive team have reinforced community connections and enhanced the community’s trust in policing, which is essential in crisis communication and navigating and addressing critical incidents that can tear the fabric of community-police dynamics.

Leveraging Technology to Standardize Community Engagement

Prior to 2017, the PPB collected reports on CE activities from each police precinct and bureau division without established guidelines or datasets to ensure consistent collection efforts.

Similarly, no safeguards were in place to prevent duplicate reports or officers misclassifying or inconsistently classifying their actions as CE activities. Although officers dedicate time and resources to hundreds of events each year, the long-term effects of these interactions cannot be accurately measured or quantified.

In 2017, following a settlement agreement between the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the PPB, resulting from US v. City of Portland, PPB started submitting annual CE activity data to the DOJ.7

The following year, PPB’s Office of Community Engagement (OCE) and Strategic Services Division (SSD) collaborated with the City of Portland’s information technology manager to develop a more comprehensive and accurate CE data collection platform.

This collective effort was partly driven by the realization that PPB data analysts routinely collected and analyzed datasets across a wide range of policing activities, including arrests, traffic stops, persons stopped, and open and closed investigations but did not focus on CE events and interactions.

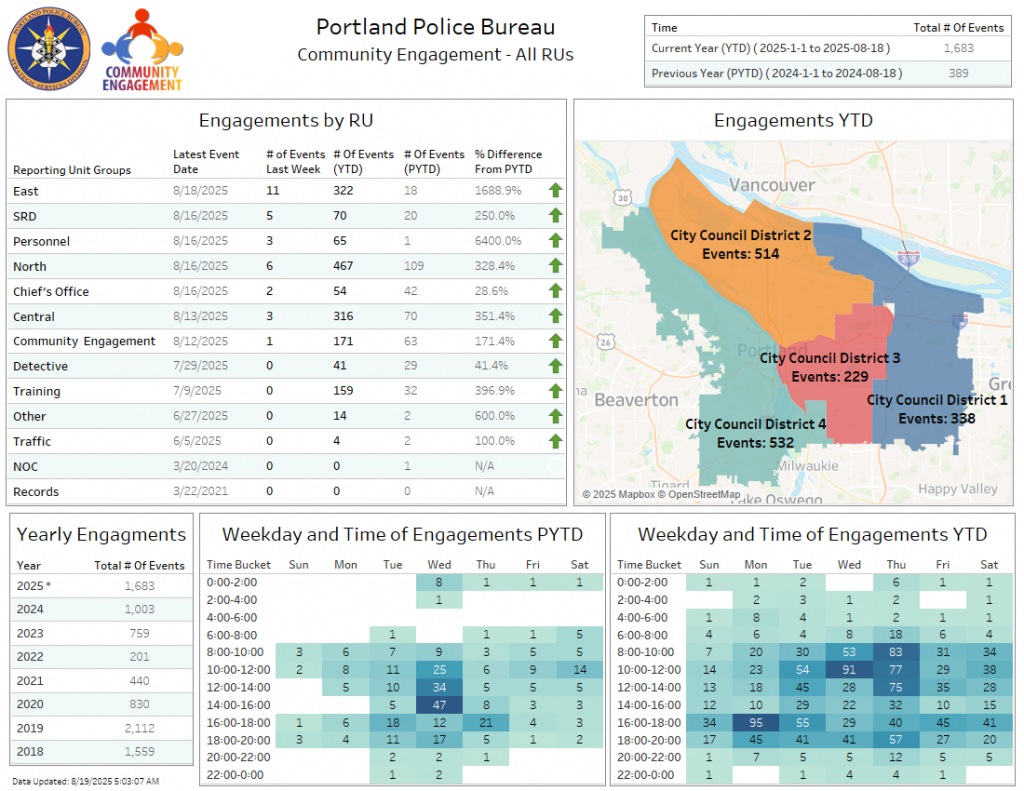

After a year of teamwork and research, including piloting the data program with internal stakeholders, the phone/desktop OCE app was designed and deployed across the bureau. In practice, each member engaging with community sectors voluntarily documents events by filling out specific categories such as location, type of event, demographic data, and a snapshot of the event, along with pending follow-up tasks (see Image 1) This data entry is linked to each member’s ID number and stored under their police profile.

PPB’s Use of Data Analysis and Academic Research As Guideposts to Enhance Its CP/CE Efforts

As noted, PPB—partly prompted by a settlement agreement with the DOJ—decided in 2018 to develop and implement a better CE data collection platform. Like many other police agencies, PPB had for years failed to include CE activities among the various police actions that data analysts spent significant time and effort on.

A robust CE data collection and analysis platform serves several purposes:

- Provides timely information to police leaders, municipal officials, and communities about evolving crime trends.

- Reflects key and emerging public safety concerns as identified by and reported to officers.

- Supports police managers in setting operational priorities and distributing resources.

This approach appears to be working; in 2024 the PPB submitted 1,003 engagements by a hundred and ninety-one personnel. In 2025, the number of submissions went up 136.8% to 2,375 submissions, while the number of PPB personnel submitting engagements went up to 284. The growth in not only the volume of entries, but the number of people in the bureau engaging speaks to the efforts and focus from the Chief’s office.

Another element of PPB’s CP/CE model involves the creation of weekly CE activity reports by the SSD team, which are distributed to individual reporting officers and units; these reports help command staff assess relevant engagement platforms and support the operational mission by highlighting interactions with specific community groups or members.

Despite its key role in the policing mission, CE activity data collection remains a low priority and often-overlooked aspect of many agencies’ data collection and analysis efforts. Police managers must understand how their officers interact with community members in noncrisis situations; such insights can only enhance the agencies’ overall organizational mission.

However, for that to happen, attention must be paid to current CE activity data collection practices, with a focus on improving the gathering, analysis, and evaluation of such data.

Strategic Integration of CE into Police Training and Education: An Example

In July 2025, PPB held its first three-day training session for the new group of demonstration liaison officers (DLO), a team of volunteer sworn members from various ranks who are key to the bureau’s response and planning for public order events.

As part of the course, PPB OCE conducted a class on community engagement and trust-building efforts related to the mission and purpose of the DLO program—to facilitate peaceful public order events.

During this session, the OCE instructor asked officers to define CE and CP and to give practical examples of how they relate to policing.

DLOs, including patrol sergeants, officers, and detectives, shared various responses, such as attending community festivals, participating in neighborhood meetings, conducting crime prevention workshops, running police youth camps, and engaging with community members during police calls. They provided numerous examples of how these touchpoints with the community became potential engagement opportunities that extended beyond the initial contact.

The DLO class discussion effectively demonstrated how the abstract concepts of CP and CE are applied in real-world situations. Each member, based on their role, has a different understanding of CP and CE and how they align with the specific duties of patrol, investigations, management, or command.

Because of the urgent and routine issues patrol officers regularly handle, they tend to see and interpret CE principles quite differently from police executives. However, each interaction between department members and the community remains a vital data point for tracking and analysis, supporting police efforts, including building trust and addressing livability concerns.

Police Executives Paving the Way for Research-Informed Policing

PPB’s community engagement platform illustrates how strategic CE efforts backed by research, analysis, and integration into police units can improve criminal investigations and enhance crime prevention programs.

Furthermore, PPB’s CE platform has helped increase public trust and confidence in police actions, as well as encourage community stakeholder involvement in police activities and crime prevention initiatives.

Conclusions

PPB’s CE platform demonstrates how strategic CE initiatives, grounded in research and analysis, can help achieve important policing goals, such as reducing crime and the related fear of crime, and enhancing criminal investigation and crime prevention efforts.

The beneficiaries of this CE strategy include both the community and the police. Achieving this social equilibrium is more than an ideal; it is a realistic, actionable goal. It offers hope: police officers can fulfill their responsibilities while staying true to their purpose of serving and protecting effectively, and the community can feel heard, involved, and empowered to participate in community policing—taking the helm and steering that ship together. d

Notes:

1COPS Office, Community Policing Defined (2009), 1.

For more on community policing, see International Association of Chiefs of Police, Navigating the Path to Public Trust: Tools for Building, Maintaining & Enhancing Community Policing.

2Portland.gov, “Coalition of Advisory Groups.”

3Keith Potter, “Prof Ben Bradford: ‘Trust and Confidence Is about More Than Visibility – It’s about Presence and Engagement,’” Policing Insight, July 11, 2025.

4ASU Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, “Step 5: Be True to POP” from Ronald V. Clark and John E. Eck, Crime Analysis for Problem Solvers in 60 Small Steps (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2016).

5Portland.gov, “0024.00 Community Policing Purpose,” Police Directives.

6Alma McCarty, “73-Year-Old Asian Man Attacked Beaten with Stick While Fishing at Portland’s Eastbank Esplanade,” KGW, updated April 6, 2024.

7 Portland.gov, “DOJ Settlement.”

Please cite as

Leo Harris et al., “Steering the Ship: The Portland Police Bureau’s Community Policing Model,” Police Chief Online, January 14, 2026.