On January 1, 2016, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began collecting information about crimes involving animal cruelty from law enforcement agencies that participate in the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). NIBRS is the United States’ primary database for collecting and archiving crime data. Animal cruelty is defined by the FBI as “intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly taking an action that mistreats or kills any animal without just cause, such as torturing, tormenting, mutilation, maiming, poisoning, or abandonment.” It is classified as a “crime against society” with four different types of animal cruelty being distinguished: (1) simple/gross neglect, (2) intentional abuse and torture, (3) organized abuse/animal fighting, and (4) animal sexual abuse.1 Previously, these crimes either went unreported or were lumped into an “all other offenses” category, which made it difficult for law enforcement agencies to develop an understanding of who was committing the crimes and whether there were any connections between the crimes perpetrated against animals and those involving human victims. Animal abuse has been linked to certain types of violence against humans; therefore, it is important for authorities to realize that there is a relationship between offenders who are involved in animal cruelty and other forms of violence.

In August 2014, there was a short interview of Dr. Randall Lockwood for the monthly podcast series The Beat, from the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office) about the link between animal cruelty and domestic violence, a topic now well-known among police officers and social workers.2 More recently, John Thompson, the former deputy executive director and chief operating officer of the National Sheriffs’ Association, who is now the executive director of the National Animal Care and Control Association (NACA), explained why law enforcement officers should pay close attention to animal cruelty investigations:

If you pay attention to animal cruelty, you may be able to identify—or even avert—other crimes more quickly…. Paying attention to animal cruelty not only protects animals, but the families and communities in which they live.

Thompson cited the value of these data for “effective targeting of resources” and to “determine where interventions are needed or are working and track how animal cruelty is related to other crimes.”3

For the first time, actual data exist in NIBRS that can lead to a better understanding of how animal cruelty is linked to other crimes. By knowing about the other crimes that have happened concurrently with animal cruelty and through close partnerships between animal control professionals and law enforcement officers, both groups can learn to recognize the types of incidents and types of offenders involved in them. It might even be possible to prevent a crime from happening simply by paying attention to offenders who are already known to animal control officers.

Background

Domestic violence perpetrated against family members is common in society and is a large public health concern.4 In addition, it is well known that child abuse and neglect often co-occur in households where animals are abused or neglected. Acts of domestic violence, also known as intimate partner violence (IPV), involving a family pet show the darker side of what is known as the “human-animal bond.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have highlighted the significant public health and economic consequences of IPV. They cite information from U.S. crime data indicating that a staggering 16 percent of homicide victims are killed by a domestic or intimate partner and that many IPV victims suffer both physical and mental trauma. In a 2018 study, it was concluded that there is an increased risk to victims (both human and animal) of suffering “severe or fatal injuries” when the IPV suspect has a history of abusing pets in the household.5 The costs to society are also enormous, with an estimated $3.6 trillion in medical expenses, lost productivity, criminal justice expenses, and other costs.6 Previous research also indicates that those who perpetrate IPV and who are known to harm animals are also more likely to have committed other crimes in the community (e.g., property crimes, drug offenses, and other crimes against persons) both before and after their crimes involving animals.7

The use of data from collections, such as NIBRS, can aid data-driven law enforcement, known as intelligence-led policing.8 In a 2018 Police Chief article, technology subject matter expert Rich LeCates gave an example of how intelligence-led policing was applied to domestic violence offenders in North Carolina. In the example, he says that it was learned that domestic violence offenders were often found to be “connected with other criminal activity such as drugs, assault, and robbery.” LeCates concluded,

knowing that perpetrators of one type of crime are likely to commit other types of crime makes it easier for law enforcement to track and identify these individuals, if they are picked up for other crimes.

Law enforcement can then try and “warn them of the consequences of continued violence and, hopefully, deter them from further abuse.”9 It is with these thoughts in mind that the 2018 animal cruelty data from NIBRS were examined to see what other crimes are most commonly associated with animal cruelty and to determine if any of the information available in the database might be helpful to law enforcement officers for identifying perpetrators likely to commit other crimes. The preliminary results presented herein illustrate how animal cruelty data might be used for this purpose and why it is critical for all agencies to participate by gathering the most accurate and complete data possible.

Overview of the 2018 NIBRS Animal Cruelty Data

Data for the analyses were obtained from both the 2018 FBI NIBRS website and from an anonymized data file containing the 2018 animal cruelty incident data obtained directly from the FBI. A number of different factors pertaining to animal cruelty incidents have been examined, including the location, day of the week and month that the crimes were committed, and information about other crimes that occurred in association with the animal cruelty. In addition, information about the offenders such as gender, age, and race and the time

of day that crimes occurred are important factors that were examined in this study. The animal crime analyses discussed may help police officers identify those in the community at risk of committing other crimes.

|

|

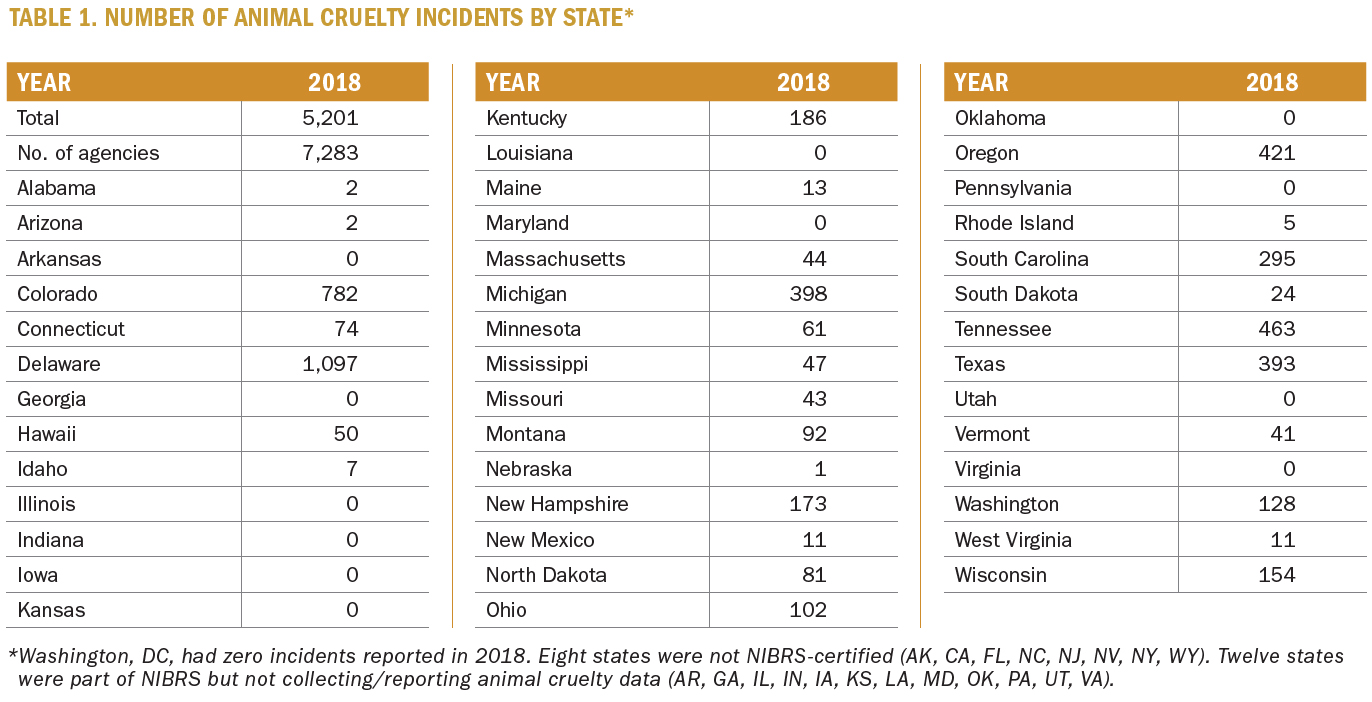

Table 1 contains a summary of all the animal cruelty incidents that occurred in 2018 for the states that were collecting data for that year. As shown in Figures 1a and 1b, the majority of the reported animal cruelty incidents had no other crimes associated with them and involved only a single offender (versus multiple offenders). This is consistent with other crimes, in that “the vast majority of incidents involve only a single offender, single victim, and single offense.”10 The majority (68 percent) of incidents of animal cruelty involved simple/gross neglect, with a smaller fraction (29 percent) involving incidents of intentional cruelty. The remaining 3 percent of all animal cruelty incidents involve the two other types of animal cruelty (animal fighting and sexual abuse) and any combination of up to three types, as defined by NIBRS.

Other Crimes Associated with Animal Cruelty

Of the incidents that are considered intentional cruelty, about 20 percent have other crimes associated with them. This is a larger fraction than the case for crimes of simple/gross neglect, for which only 3 percent of incidents were associated with other crimes. These results are consistent with other research on violence by animal cruelty offenders, which showed that animal cruelty offenders often have other offenses in their criminal history. Working with the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) of the FBI, researchers analyzed the crime histories of 259 offenders arrested for active animal cruelty. Active animal cruelty includes physical harm as opposed to more passive forms of abuse such as neglect. In their study, the team demonstrated that 60 percent of the offenders had engaged in IPV prior to, concurrently with, or after the animal cruelty offense.11 While data on IPV and associated animal cruelty are not yet available, they will be once the 2019 animal cruelty NIBRS data are released. (The FBI started collecting data on domestic and family violence in 2019.)12

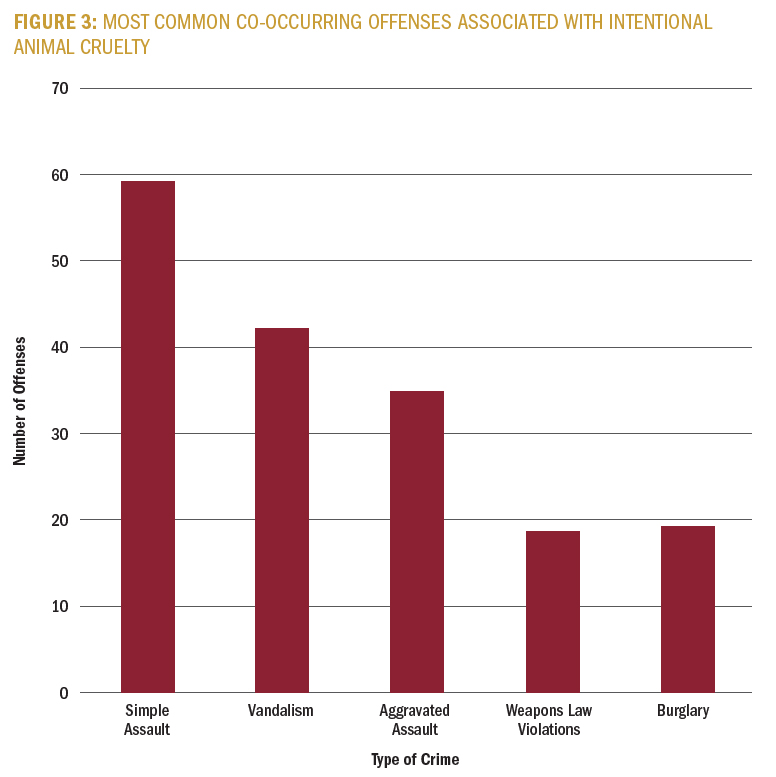

The data also show that certain crimes most frequently occur at the same time as incidents of intentional animal cruelty, including simple assault, vandalism, aggravated assault, weapons law violations, and burglary. (See Figure 3.) Interestingly, these are some of the same crimes identified by the FBI BAU study. For this study, the author analyzed different types of crimes found to occur in association with both animal neglect and intentional animal cruelty incidents, and over two-thirds of all incidents (68 percent) occurred at a residence or home location.13 In addition, there were fewer incidents of intimidation and slightly more incidents involving drugs and narcotics associated with animal cruelty involving simple or gross neglect and more vandalism, burglary, and intimidation associated with incidents of intentional cruelty. This is the kind of information that could not only prevent harm to animals but would be helpful for law enforcement to be aware of when deciding whether or not to investigate a domestic incident involving animal cruelty. Also, it might help prevent an incident of family violence.

The data also show that certain crimes most frequently occur at the same time as incidents of intentional animal cruelty, including simple assault, vandalism, aggravated assault, weapons law violations, and burglary. (See Figure 3.) Interestingly, these are some of the same crimes identified by the FBI BAU study. For this study, the author analyzed different types of crimes found to occur in association with both animal neglect and intentional animal cruelty incidents, and over two-thirds of all incidents (68 percent) occurred at a residence or home location.13 In addition, there were fewer incidents of intimidation and slightly more incidents involving drugs and narcotics associated with animal cruelty involving simple or gross neglect and more vandalism, burglary, and intimidation associated with incidents of intentional cruelty. This is the kind of information that could not only prevent harm to animals but would be helpful for law enforcement to be aware of when deciding whether or not to investigate a domestic incident involving animal cruelty. Also, it might help prevent an incident of family violence.

Demographics of Animal Cruelty Offenders

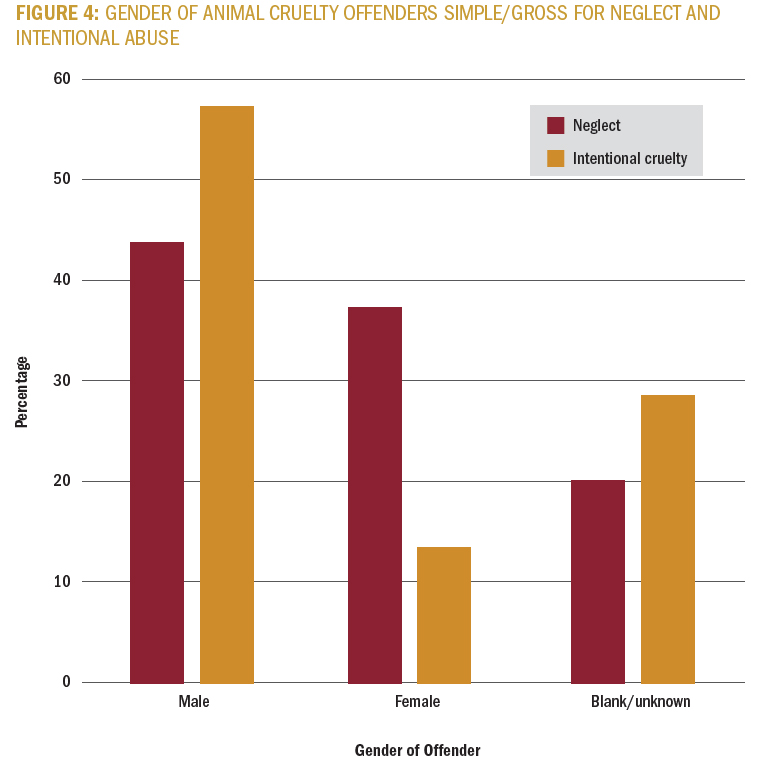

NIBRS collects data on demographics such as sex, race, and age of offenders for all crime types, including animal cruelty. As shown in Figure 4, there is a larger percentage of males engaged in intentional cruelty relative to neglect; conversely, females are more likely to be involved in incidents of neglect instead of intentional cruelty. It should be noted, however, that NIBRS is missing much data for both neglect and intentional cruelty incidents, with a full 20 percent of neglect incidents having no information about the offender’s gender and nearly 30 percent of intentional cruelty offenders being of unknown gender. Given the nearly 4:1 ratio of males to females in cases of intentional cruelty, it is likely that a significant fraction of the unknown offenders are also males. These results are consistent with the FBI BAU study, where a full 97.3 percent of offenders were male, as well as previous studies about the differences between males and females when it comes to cases of intentional animal cruelty.14

NIBRS collects data on demographics such as sex, race, and age of offenders for all crime types, including animal cruelty. As shown in Figure 4, there is a larger percentage of males engaged in intentional cruelty relative to neglect; conversely, females are more likely to be involved in incidents of neglect instead of intentional cruelty. It should be noted, however, that NIBRS is missing much data for both neglect and intentional cruelty incidents, with a full 20 percent of neglect incidents having no information about the offender’s gender and nearly 30 percent of intentional cruelty offenders being of unknown gender. Given the nearly 4:1 ratio of males to females in cases of intentional cruelty, it is likely that a significant fraction of the unknown offenders are also males. These results are consistent with the FBI BAU study, where a full 97.3 percent of offenders were male, as well as previous studies about the differences between males and females when it comes to cases of intentional animal cruelty.14

There is also information in the 2018 animal cruelty data about both the race and the age of animal cruelty offenders (both male and female). Care must be taken in drawing too many conclusions about these data, given that race will depend on the demographics of the jurisdictions from which the data were collected. However, if one looks at the entire database of animal cruelty incidents (n=5324), the data show that 55.5 percent of offenders were white, 16.3 percent were black/African American, 0.8 percent were Asian, 0.6 percent were American Indian/Alaskan Native, 0.3 percent were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 10.2 percent were of unknown race, and 16.4 percent were left blank. These numbers align to a certain extent with data from the 2019 Census Test Report for the population as a whole.15 Given that almost 27 percent of the race information for offenders is unknown or was left blank, it is hard to draw too many conclusions about these data. Future analyses should include ethnicity data, and hopefully, in future years, the data collected will be more comprehensive, with fewer missing or unknown data points.

Finally, in the aforementioned FBI study, the mean age of active animal cruelty offenders was 34 years. In the 2018 NIBRS animal cruelty data, the mean age of the 1,525 intentional animal cruelty offenders is 36 years.

Spatio-temporal Association of Animal Cruelty and Other Types of Crime

In 2015, the journal Crime Science produced a special thematic issue on the spatio-temporal patterns of crime in order to “demonstrate the value of this approach for advancing knowledge in the field.” According to the editors of this special issue, there has been a “paucity of research into the patterns and manifestations of crime events in both space and time.” They noted that, whereas many studies have looked at the location where crimes occur that these studies, for the most part, have been “atemporal.”16 Former British officer and criminal justice professor Jerry Ratcliffe reviewed the monthly and seasonal trends of various types of crimes and noted that even the “hour-by-hour” variations all have “potential policy implications…. [and] have real possibilities in better understanding and preventing crime and criminality.” He showed how temporal signature charts showing the hourly volume of calls for different types of crime incidents can be helpful in illustrating the times of day and night when different crimes occur and can help inform law enforcement about patterns of repeat victimization and repeat phenomena that may have value for uncovering associations between different types of crimes throughout the day.17

“Those who perpetrate IPV and who are known to harm animals are more likely to have committed other crimes in the community.”

The Office for Victims of Crime in the U.S. Department of Justice reviewed the 2011 NIBRS data on the timing of sexual victimizations by victim age and time of day. The data showed “distinct time periods when the majority of children and adults are victimized,” with the majority of incidents occurring between 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. for children under 18 years of age, with peaks in frequency occurring around normal meal and snack times and a decline in frequency after 4:00 p.m. For adults over 18 years of age, the frequency of assaults is relatively constant throughout the daytime with a small peak around midday and a noticeable increase in the number of such assaults occurring between the overnight hours of 10:00 p.m. and 3:00 a.m. The analysis highlighted the value of such data to “victim service providers and law enforcement officers” for identifying the timing of different types of crimes and for helping them to “develop effective strategies for responding to and preventing these crimes.”18

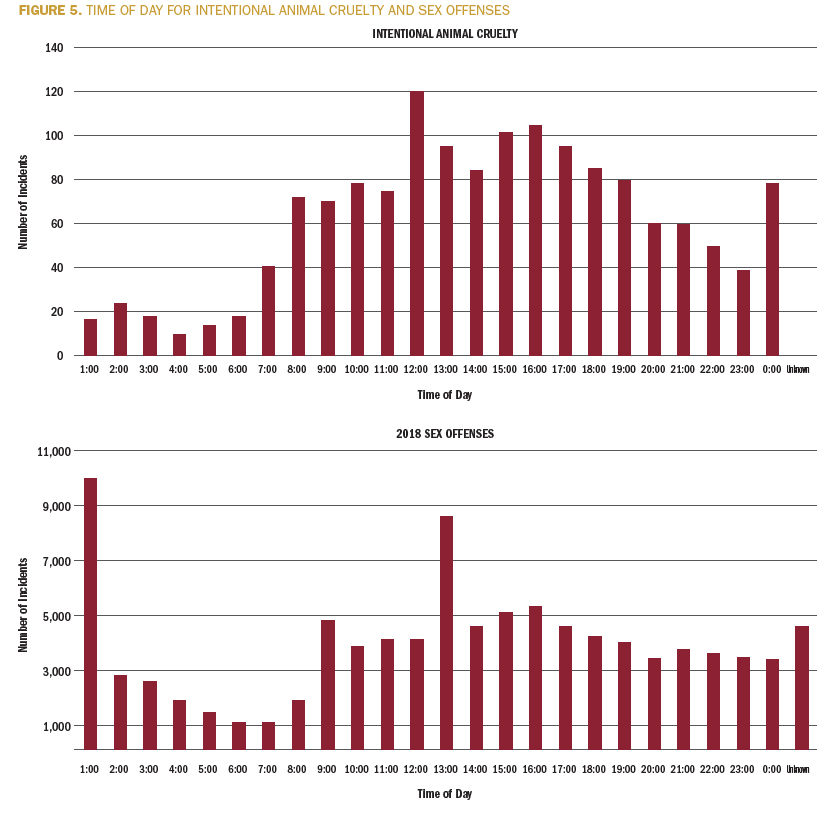

Figure 5 shows temporal signature charts, similar to those discussed by Ratcliffe, for intentional animal cruelty and sex crimes. The data for intentional animal cruelty is from the 2018 database the Animal Welfare Institute obtained from FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services, whereas the data for sex crimes is from the 2018 FBI NIBRS website. The animal cruelty chart illustrates how intentional animal cruelty is low throughout the nighttime and appears to increase in frequency starting around 7:00 a.m.–8:00 a.m. There is a gradual increase throughout the morning with a peak around midday, and then there is a decline throughout the afternoon with another slight increase around 3:00 p.m.–4:00 p.m. in the afternoon.

The chart for sex crimes shows some of the same features as the chart of the intentional animal cruelty, and the pattern appears consistent with the conclusions from the 2011 analysis of sexual victimization data from NIBRS discussed previously. These data are also consistent with an analysis of 2015 NIBRS data that found that more than two-thirds of juvenile sexual assaults occurred during the daytime, from about 8:00 a.m. until about 8:00 p.m.19 These results are consistent with the notion that many intentional animal cruelty incidents and at least some cases of juvenile sexual assaults happen during the day, when few or no other adult guardians are at home to interfere or bear witness.

Conclusion

| IACP Resources

■ Domestic Violence Model Policy ■ “Animal Protection and Welfare Training Becomes Essential to Law Enforcement” (article) ■ “The Role of Veterinary Forensics in Animal Cruelty Investigations” (article) |

According to a report in the April 2020 National Link Coalition’s monthly newsletter, “The Kentucky Fraternal Order of Police has endorsed a bill in the Kentucky legislature (HB 216) to include ‘violence against an animal used as coercive conduct.’” If passed, the bill would help to protect family pets from abuse associated with incidents of domestic violence.20 This is definitely a step in the right direction and the need for more legislative and legal remedies for victims of abuse, regardless of species, are sorely needed. The data on animal cruelty reported to FBI NIBRS can help law enforcement officers in their mission to protect the safety of the public and make informed decisions about when and where to look for offenders who might be targeting both animal and human family members.

Notes:

1Daniel De Sousa, NIBRS User Manual for Animal Control Officers and Humane Law Enforcement (National Council on Violence Against Animals), 1.

2Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, “The Link Between Animal Cruelty and Domestic Violence,” The Beat (podcast), August 2014.

3John Thompson, “Why Addressing Animal Cruelty Matters,” Police1, April 17, 2019.

4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Preventing Intimate Partner Violence.”

5Andrew M. Campbell et al., “Intimate Partner Violence and Pet Abuse: Responding Law Enforcement Officers’ Observations and Victim Reports from the Scene,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence (March 2018).

6CDC, “Preventing Intimate Partner Violence.”

7Tia Hoffer et al., Violence in Animal Cruelty Offenders, Springer Briefs in Psychology (New York, NY: Springer International Publishing, 2018).

8Rich LeCates, “Intelligence-Led Policing: Changing the Face of Crime Prevention,” Police Chief Online, October 17, 2018.

9FBI, “2018 National Incident-Based Reporting System”; A. Shaffer (Criminal Justice Information Services), personal communication, 2019.

10David J. Roberts and Paul Wormeli, “Why Participating in NIBRS Is a Good Choice for Law Enforcement,” Technology Talk, Police Chief 81, no. 9 (September 2014): 72–74.

11Hoffer et al., Violence in Animal Cruelty Offenders.

12FBI, UCR Program Quarterly, April 2017.

13Julie M. Palais, “Crunching the Numbers on Cruelty: The National Incident-Based Reporting System Delivers Preliminary Data on Animal Cruelty Investigations,” Sheriff & Deputy (September/October 2020): 70–73.

14Hoffer et al., Violence in Animal Cruelty Offenders; Emma Alleyne and Charlotte Parfitt, “Adult-Perpetrated Animal Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review,” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 20, no. 3 (July 2019): 344–357; Harold A. Herzog, “Gender Differences in Human–Animal Interactions: A Review,” Anthrozoös 20, no. 1 (2007): 7–21.

15U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” 2019.

16Andrew Newton and Marcus Felson, “Editorial: Crime Patterns in Time and Space: The Dynamics of Crime Opportunities in Urban Areas,” Crime Science 4, no. 11 (2015): Article 11.

17Jerry Ratcliffe, “Crime Mapping: Spatial and Temporal Challenges,” in Handbook of Quantitative Criminology, eds. Alex R. Piquero and David Weisburd (New York, NY: Springer, 2010), 5–24.

18Office for Victims of Crime, “National Incident-Based Reporting System: Using NIBRS Data to Understand Victimization.”

19Erica Smith et al., “Leveraging NIBRS to Better Understand Sexual Violence,” Police Chief 85, no. 5 (May 2018): 16–18.

20National Link Coalition, “Fraternal Order of Police Supports Kentucky Link Bill,” The LINK-Letter 13, no. 4 (April 2020): 5.

Please cite as

Julie Palais, “Animal Cruelty Hurts People Too: How Animal Cruelty Crime Data Can Help Police Make Their Communities Safer for All,” Police Chief 87, no. 12 (December 2020): 42–48.