Concerns regarding racial bias in policing are a persistent and growing issue in communities across the United States , leading to increased scrutiny for police agencies’ policies, practices, and actions. One approach police agencies can employ to address these concerns is proactive self-assessment and auditing. To advance, agencies must focus on sustainable change through implementation (ensuring changes are put into practice effectively), assessment (continuously monitoring effectiveness), review and modification (adjusting processes as needed), and continuation (embedding improvements into the agency’s culture for long-term impact). Such initiatives allow police departments to analyze their policies and practices, identify areas for improvement, and realize reforms that foster community trust.

The Charleston, South Carolina, Police Department (CPD) undertook a voluntary racial bias audit as part of its commitment to transparency and self-improvement. Spanning nine years, three chiefs, and one interim chief, this initiative set a precedent for police agencies aiming to proactively evaluate their practices and improve on all fronts, as well as offering a roadmap and lessons learned.

Background and Context

Overview of the Charleston Police Department and the City

The CPD is the largest municipal police agency in South Carolina, with an authorized complement of 454 officers. Charleston is a historically rich city situated in the state’s coastal region, known as “the Lowcountry.” It boasts a diverse population of approximately 155,000 people and a vibrant tourism sector with millions of yearly visitors and several universities, contributing to the city’s dynamic environment.1 Along with these attributes is a complex past, particularly concerning slavery and the slave trade, in which Charleston played a major role from the 1600s through the 1800s. This history has influenced contemporary discussions on racial relations and how they reverberate through the city’s institutions, including its police department.

Community and Organizational Motivations

The aforementioned discussions were further fueled by a more recent tragedy that occurred within the city. The racially motivated mass shooting at Emanuel AME Church in June 2015 devastated the Charleston community. The attack, carried out during a Bible study session, resulted in the deaths of nine African American congregants. This tragedy intensified discussions about race relations in Charleston and the role of the police in fostering community trust and safety. In response to community concerns, the CPD and several community representatives launched the Illumination Project, a collaborative series of meetings that aimed at improving police-community relationships.2 Through listening sessions and research, the initiative shaped the CPD’s 2017–2020 Strategic Plan, with a focus on five key areas: culture, relationships, training, policies, and community policing.

Recognizing the need and calls from some community groups for an independent assessment, CPD initiated a voluntary racial bias audit to be performed by an independent research partner. It was voluntary because the department was not compelled by a consent decree or response to a high-profile use-of-force incident. Given this, the CPD had greater autonomy in guiding the process, resulting in a collaborative atmosphere that differed significantly from one that might have been imposed externally.

Methodology of the Audit and Assessments

Conducting the Audit

The CPD received approval from the Charleston City Council in December 2018 to hire an external research team to examine policies and procedures in five key areas: traffic stops, use of force, complaints, community engagement, and personnel practices. The audit team employed a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating interviews, document reviews, community focus groups, and statistical analyses using CPD’s administrative data.3 Key findings revealed disparities in policing outcomes, though they could not be definitively attributed to bias. The audit team offered 72 recommendations for the CPD, including a final recommendation to engage an external assessor to evaluate the department’s implementation of the proposed changes.

Implementation and External Review

Following the audit, the CPD committed to implementing the recommendations. Over the next three years, the agency developed a structured plan, including assigning responsible parties, creating timelines, tracking activities on an internal spreadsheet, and maintaining transparency by constructing and updating a public-facing audit tracking dashboard and progress reports.4

With the city government’s support, following implementation, the CPD achieved the final recommendation by engaging a multidisciplinary team of researchers to conduct an assessment of the implementation of the audit recommendations. The assessment team used similar methods to those used by the audit team, including in-depth interviews with key CPD project leaders and community stakeholders; a document review; quantitative disparity analysis using CPD data on motor vehicle stops, use of force, and complaints; and a community engagement component that included publicly advertised focus groups. Concurrently, the CPD created a community perceptions survey that was fielded in collaboration with its Citizen Police Advisory Council (CPAC). The second assessment report was issued in November 2023.

Of the original 72 recommendations from the audit, it was possible for the external team to assess 67 of them. It concluded that the CPD made a “good-faith effort to implement the recommendations.”5 Some suggestions were provided on how to improve the implementation of those recommendations that were not determined to be fully and effectively realized. An additional 24 recommendations were provided by the assessment team for the CPD to consider.

The CPD issued its final implementation report on the audit in June 2024, accompanied by presentations to the City Council and the CPAC.6 This included a full review of all 96 recommendations that the department received from the audit and the implementation assessment. Following the review process, the CPD determined that any remaining work on the recommendations would be incorporated into its forthcoming strategic plan.

Lessons Learned

The CPD learned many valuable lessons throughout the multiyear, multi-component process that may prove useful to other agencies considering or embarking on similar projects.

Comprehensive Planning

Without proper foresight and planning, it is easy to be trapped in a maze. Establishing clear objectives and communication strategies from the start is essential to prevent an indefinite cycle of implementation and assessment. Each department needs to plot the path forward and define what the end looks like in terms that all stakeholders will understand before the effort begins. This includes defining what will be communicated about the project and when. Leaving this open-ended sets departments up for getting lost in a maze without a clear exit strategy. Upon reflection, the CPD could have more effectively communicated all the steps involved in the process and when it would consider the process completed; however, this was not done initially. As a result, this years-long cycle of assessment and implementation on this topic could have continued indefinitely.

Departments embarking upon similar work must also be proactive and carefully consider the title of any requests for proposals, objectives, and goals of the project. The department must assist, as much as permitted, in setting the overall tone, agreeing to the objectives and goals, and understanding which metrics are being used to judge their productivity. These key features set the stage for the entire body of work and how police officers, staff, and the public will perceive it. During this part, it is critical to set appropriate expectations of success, completion, and how to address possible findings. Proper planning ensures that all stakeholders understand the scope and expected outcomes.

Defining and Explaining Key Terminology

One of the most critical lessons from this project is that every word and definition carries significant weight. Precision in language is essential—it shapes perceptions, expectations, and the credibility of the work. It is incredibly important to define the scope in neutral terms. The objective should be to explore and understand patterns—the audit should not begin with assumptions about outcomes. This helps all stakeholders—community, media, and officers—understand that the audit is an exploration, and the findings are not foregone conclusions.

“One of the most important lessons learned for the CPD was the necessity of controlling the agency’s narrative”

In this case, the CPD agreed to an audit labeled as an assessment of “racial bias in policing” without fully recognizing the implications of the term “bias.” By doing so, it inadvertently set expectations that bias could be definitively identified. As a result, the terms “bias” and “disparity” were used interchangeably, both internally and externally, leading to confusion and misinterpretation. Communicating an audit on bias or disparities requires absolute clarity from beginning to end. Using terms like “bias” without careful consideration can imply its existence and set unrealistic expectations.

Disparities in policing outcomes are influenced by numerous complex social factors beyond the control of any police department. Disparities are omnipresent and pervasive throughout society and are seen in health care, education, housing, income, and most other societal outcomes. They have multiple, overlapping, influencing factors, including historical inequalities, unbalanced economic opportunities, and other systemic influences. Identifying that they exist is one thing, but understanding solutions to addressing them is immensely complex, especially within the criminal justice system. Social scientists often cannot adequately account for all of them in administrative data from police departments. This is why causal claims are sparse in this area of study. The CPD’s audit did not conclude that disparities in its data were evidence of bias. Data were inadequate to support that claim. Thus, it is crucial to communicate that disparity does not automatically equate to bias. Oversimplifying disparities as bias is misleading and risks undermining trust with the community. It is the police department’s responsibility to help the community understand these nuances.

Benchmarking

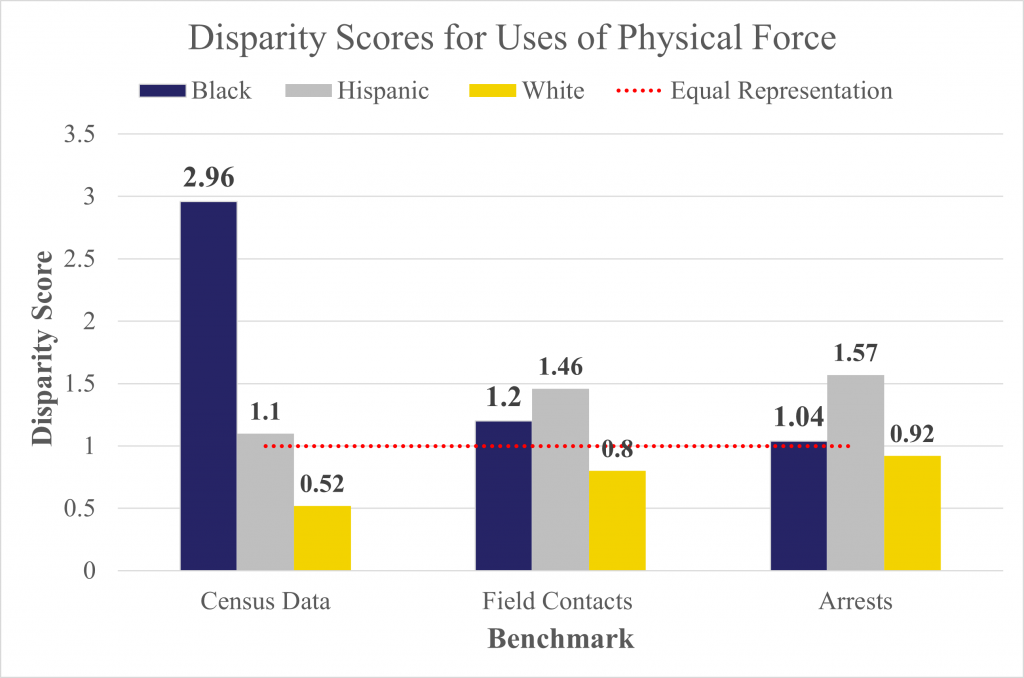

Disparity analyses often employ simple, descriptive calculations that do not require sophisticated methods. In policing, they are used to examine differences in outcomes for similarly situated individuals (e.g., the rate of arrests for Black individuals). Outcomes are then compared to a reference group (e.g., the rate of arrests for White individuals) to quantify the differences. A common method in these analyses uses the most recent U.S. Census population to approximate the population at risk for any outcome of interest. For example, such a population-based calculation is appropriate in examining the prevalence of COVID-19 among different racial groups within the community.

But, even though this method is relatively easy to perform—because Census data are inexpensive and easy to obtain—it is problematic in policing studies. This is because police respond to calls for service, and since crime is not evenly distributed in space and time, neither are the police. Consequently, community members do not all have an equal likelihood of interacting with police. Many studies have confirmed this and subsequently wrestled with the issue of finding a more accurate benchmark.7 These studies commonly conclude that it is difficult to arrive at a reliable and valid benchmark in this discipline and that all benchmarks have weaknesses. However, some are clearly superior to others. Activity-based benchmarks that provide a better estimation of community activity and likelihood of encountering police (such as suspect descriptions and those arrested) are often preferred.

As a demonstration of how these benchmarking decisions can affect a disparity analysis of police activity, refer to Figure 1, which shows the resulting disparity scores from CPD officers’ uses of physical force. Disparity scores vary dramatically based on the selected benchmark. The U.S. Census data benchmark (on the lefthand side) shows a disparity for Black community members almost three times the size of the other two benchmarks of field contacts and arrestees, which provide arguably more realistic estimates of the population at risk for uses of police force. These decisions have dramatic impacts on the conclusions and implications of these studies and how they are interpreted by the police and the communities they serve. When at all possible, police departments must carefully consider which metrics are most appropriate based on the type of analysis and available data.

Internal Commitment and Real Change

Large-scale initiatives, such as a department-wide audit, require sustained focus and internal support. Given their emotional toll on personnel, as well as resource demands associated with required output, energy, and time, police departments must ensure that audits lead to tangible improvements rather than serving as public relations exercises. Leaders must speak openly and frequently about the project with staff at all levels, reinforcing the concrete benefits that the department will realize as a result. This strategy acknowledges the internal workforce and its importance in the effort. Officers and staff must understand and engage with the process for meaningful change to occur.

In the CPD’s case, the audit led to substantial improvements in several areas, including its data transparency, recruitment strategies, and the agency’s reputation as an evidence-based policing institution. Policy changes facilitated improved documentation, leading to more comprehensive data on motor vehicle stops. These data can now be linked with outcomes that are tracked at the state level, creating a complete record of each stop to support a wider range of analyses. Additionally, modifications in use-of-force data entry provided a more detailed breakdown of these incidents, differentiating between each officer’s actions and the impact on each individual involved.

“Success depends on having the right systems and personnel working together to achieve shared goals.”

The audit underscored CPD’s uniqueness in recruitment and training, recognizing its program as one of a kind. The audit process also served as an opportunity to demonstrate to candidates that CPD’s operations are guided by evidence, transparency, introspection, and customer service. By aligning recruitment efforts with these principles, the CPD attracted candidates who fit well within its culture. The recruitment unit leveraged the audit findings to develop a strategic plan, using the audit as a catalyst to define and refine the recruitment process.

The CPD’s commitment to evidence-based practices laid the foundation for new opportunities, increased funding, and greater recognition. The agency demonstrated resilience in the face of challenges, transforming obstacles into opportunities for growth. With this foundation and shortly after the completion of the audit, the CPD was awarded a federal Smart Policing grant, emphasizing problem-oriented policing and data-driven improvements. New staff positions, including a research director and a compliance inspector, were added to further institutionalize evidence-based practices. Beyond immediate gains, the audit instilled a culture of organizational introspection—a critical factor in driving meaningful change. CPD’s transformation is not just a temporary shift but a legacy that will shape the agency for years to come.

Effective Messaging

Police departments should be the primary sources of their own information. Any work emerging from the arena of racial disparities in policing can be controversial and divisive. How departments communicate about these efforts is just as important as what departments communicate. As a result, departments must control the narrative, clearly define their actions, and be proactive in addressing questions to truly engage with their communities. This also prevents misinterpretations and distortions from permeating public dialogue.

When the CPD released the audit report through traditional media, there were different interpretations of the same information, leading to misinformation and confusion. This experience led to the creation of the CPD Newsroom, a platform designed to be a direct source for the department’s communications.[8] The goal is to ensure consistent messaging and avoid misinterpretations by external parties. Establishing a primary communication platform ensures that the department retains control over its narrative. The lessons learned from the audit emphasize the need for precision, honesty, and being the primary source to control the narrative and build public trust.

The Structure of Sustainable Change

The audit process was never about checking a box or fulfilling a requirement—it was about achieving practical, lasting change. No successful industry avoids self-evaluation. As stated earlier, agencies seeking to create lasting changes must follow through on implementation, assessment, review, modification, and continuation of any new policy or practice. Given that such an undertaking necessitates the collaboration of personnel across various roles within an organization, careful coordination is essential. Sustainable change requires seamless collaboration of three different levels: strategic, operational, and tactical. The strategic level is composed of chiefs and leaders who set the vision and direction for the agency. The operational level relies on managers and supervisors to translate strategic goals into actionable plans. The tactical level includes officers who execute the plan and drive day-to-day implementation. The following insights are therefore organized by stakeholders’ roles, offering guidance about the key players needed for departments embarking on a similar process.

Chiefs and Leaders (Strategic Level)

No leader can drive change alone. Building the right team is crucial to success. By building a team of diverse talents and capabilities, leaders can ensure that the work moves forward effectively and meaningfully and that progress continues even beyond individual efforts. Essential members of this team are staff with expertise on department operations, policy, data and research, public affairs, and community outreach. Additionally, involving officers and professional staff will ensure that the team is well-rounded and versed in the wide array of perspectives within the organization. Engaging city partners and community stakeholders is also important. If engaging external research partners in the process, vet them by reviewing their qualifications, reading their publications, and inquiring about their previous evaluative partnerships.

First-Line Supervisors and Middle Managers (Operational Level)

Middle managers and first-line supervisors are the linchpins of sustainable change. They translate leadership’s vision into daily practice and ensure that officers align their actions with strategic objectives. Without their engagement, change efforts risk stalling or failing. First-line supervisors bear the responsibility of bridging leadership goals with field execution. They must secure buy-in, guide their teams, and maintain accountability to ensure meaningful results. The entire process of change rests on the balance and accountability of middle management—success hinges on how well they guide, motivate, and align their teams.

Officers (Tactical Level)

Officers, who make up the majority of any police department, are the most visible representatives of the profession. Their inclusion in change initiatives is essential for successful implementation. Officers want a voice in the process—feeling heard and involved fosters commitment to the effort. They also need clarity on the reasons for the project and how it will impact them. Understanding the need for changes and their realistic benefits increases acceptance. Setting and discussing future expectations with officers will help them align with evolving departmental goals. Finally, providing a framework for success ensures a smooth adaptation to new expectations and cultural shifts. Failure to engage officers in this way can result in resistance and poor implementation of reforms.

Public Information Officers (Tactical Level)

Finally, a well-prepared public information officer (PIO) ensures that the agency is ready to respond to scrutiny with accuracy and confidence. The PIO should be the author of the agency’s information. One of the most important lessons learned for the CPD was the necessity of controlling the agency’s narrative. CPD’s PIOs played a crucial role in shifting the agency from a reactive stance to a proactive communication strategy. It is imperative to maintain consistency in messaging, disseminate the message using multiple credible voices, be the first and most reliable information source, and keep detailed records to support transparency and accountability.

Conclusion

The CPD’s audit experience reinforced that the true goal is not merely to meet compliance requirements but to create meaningful, lasting improvements. Agencies that approach audits solely as a procedural necessity will end up with superficial results that fail to create real impact. At the conclusion of this process, the CPD learned that sustainable change requires implementation, evaluation, and modification, not just project completion. Success depends on having the right systems and personnel working together to achieve shared goals. A commitment to evidence-based policing, data transparency, and proactive communication sets agencies apart as leaders in the field. The CPD’s journey provides a model for other police agencies seeking to transform challenging cultural moments into opportunities for lasting success. d

Notes:

1U.S. Census Bureau. “QuickFacts: Charleston City, South Carolina,” modified 2023.

2Charleston Illumination Project, Charleston Illumination Project: Community Engagement, Strategic Planning, and Implementation Report, 2016.

3Denise Rodriguez et al., Final Report: Racial Bias Audit of the Charleston, South Carolina, Police Department (Arlington, VA: CNA, 2019).

4Charleston Police Department, “City of Charleston Police Department Audit Tracking,” last modified February 2, 2023.

5Geoffrey Alpert et al., External Review and Assessment: Charleston Police Department’s Racial Bias Audit Implementation Final Report (2023), 8.

6Charleston Police Department, Charleston Police Department Racial Bias Implementation Final Report (2024).

7Jerry H. Ratcliffe and Shelley S. Hyland, “Police Stops and Naïve Denominators,” Crime Science 14 (2025): article 10; Greg Ridgeway and John MacDonald, “Methods for Assessing Racially Biased Policing,” in Race, Ethnicity, and Policing: New and Essential Readings, eds. Stephen K. Rice and Michael D. White (NYU Press, 2010), 180–204.

8Charleston Police Department, “CPD Newsroom.”

Please cite as

Jillian Eidson et al., “Audit. Action. Change: Insights from a Voluntary Racial Bias Audit and Organizational Transformation,” Police Chief Online, December 3, 2025.