|

See the YouTube video related to this article. |

Standing before the jury, the police officer testified, “I’m confident the person who assaulted me was wearing a blue jacket.” Moments later, the defense played a cellphone video showing the defendant in a clearly purple jacket. “Well, I guess this proves my client is innocent,” the lawyer said. The jury shook their heads, and the officer had nothing more to say.

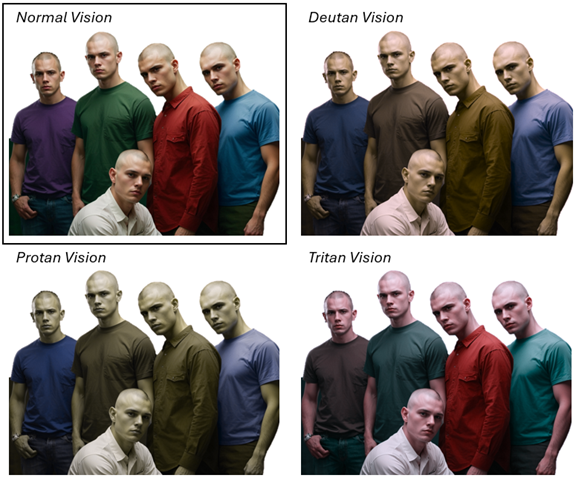

This wasn’t deceit on the officer’s part—it was a color vision deficiency, often called “color blindness.” If a person isn’t aware they have a deficit, even a mild one, their color blindness can lead to missing BOLOs, misidentifying evidence, writing the wrong color into reports, misinterpreting traffic signals, and even contributing to miscarriages of justice. Officers also must consider the color vision ability of others. Eyewitnesses may themselves be color deficient, unknowingly introducing errors into their testimony to officers.

Prevalence: A Growing and Often Unnoticed Problem

The ability to perceive color is often taken for granted, but the data tell a different story. In fact, 30 percent of people with a color deficiency aren’t aware of it.1 There are two primary color deficiency categories:

- Congenital deficiency: About 1 in 12 men (8 percent) and 0.5 percent of women are born with a genetic color vision deficiency.2

- Acquired deficiency: Color blindness acquired by people who were born with normal vision.3 It is estimated that 15 percent of the general population (have an acquired color deficiency.4

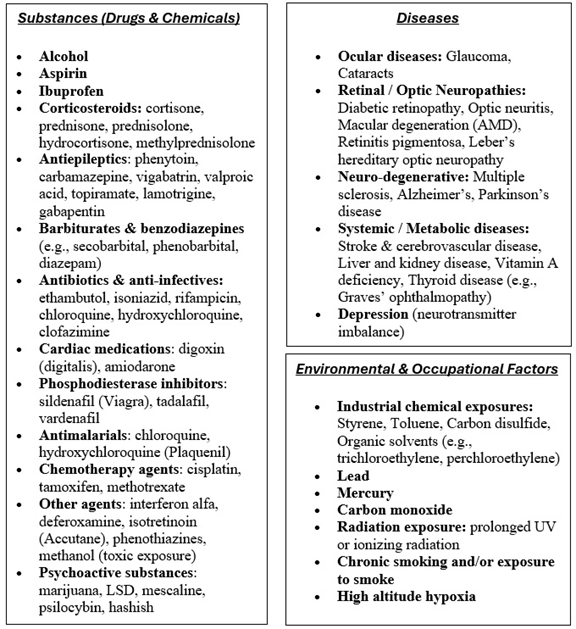

There is a misconception that color vision ability is fixed for life. In reality, perception can change due to age, medical issues, medications, and environmental exposures (see Figure 2). Many people have no idea how their ability to perceive different colors has changed.

Operational Impact in Law Enforcement

Color vision ability is not a minor detail—it is mission critical. In one survey, more than 65 percent of officers stated that intact color vision was crucial for daily duties.5 Deficiencies reduce efficiency, delay responses, and put officers and the public at risk.

Examples of mission-critical tasks include the following:

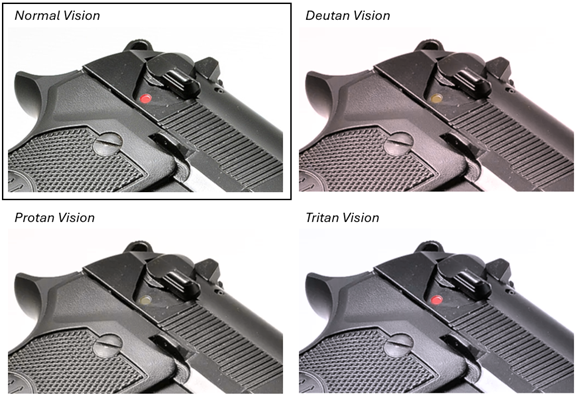

- Recognizing red gun safety setting (ON/OFF)

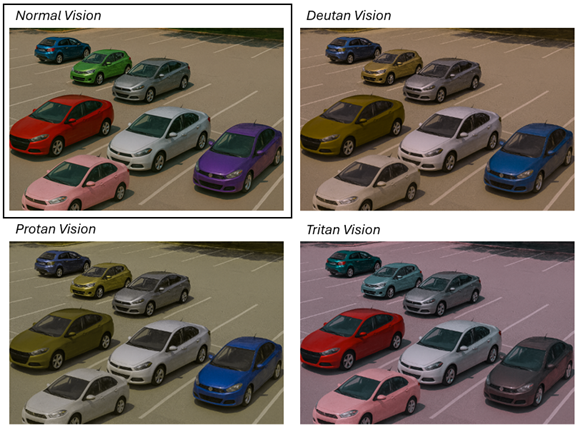

- Scene and suspect descriptions: clothing, hair, tattoos, vehicle colors

- Surveillance and video review: identifying suspects (clothing, hair, eyes, etc.) or vehicles by color

- Forensics: spotting blood on grass, leaves, or dark surfaces; identifying trace evidence

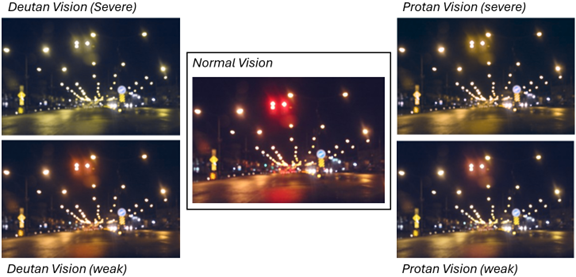

- Reading traffic light colors during a high-speed pursuit

- Using reflex sights or red-dot lasers on firearms

- Interpreting HAZMAT smoke colors

- Distinguishing explosive device wires (EOD roles)

Even an officer has perfect color vision, their colleagues and eyewitnesses may not. Up to 20 percent of reports could contain unintentional, color-based errors.

Why Traditional Tests Fail

Many police agencies still rely on outdated color vision tests developed nearly a century ago. While they may be familiar, these tests fail to detect the very deficiencies that put officers and the public at risk.

Ishihara Plates (created in 1917):

- Does not detect tritan (blue) deficiencies—the most commonly acquired color blindness

- Requires a specialized 6500K light source, which is rarely used in practice

- Ink fades over time, making older books unreliable

- Easily memorized

- Prone to test administration and timing errors

Farnsworth D-15 (created in the 1930s):

- Depending on how errors are scored, 25–50 percent of color-deficient candidates pass6

- Results vary by test administrator, lighting, and timing

- Susceptible to gaming by candidates who have practiced

The problem is not theoretical. A $1.4M U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) study in 2025 demonstrated that even tritan (blue) deficiencies—invisible to Ishihara testing—had a statistically significant, negative effect on police officers’ job task performance. Yet these very deficiencies continue to go undetected by the tests most commonly used today.

The FAA’s Precedent: A Modern Model

After years of debate and research, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) came to the same conclusion: traditional color vision tests were inadequate for ensuring safety in high-stakes professions.

The FAA eliminated the Ishihara and Farnsworth D-15 as acceptable measures and, as of January 2025, recognizes only three high-precision, computer-based tests:7

- CAD (Colour Assessment & Diagnosis)

- Rabin Cone Contrast Test

- Waggoner CCVT (WCCVT)

Why? Because these tests are

- Accurate: nearly 99 percent accurate, with 98 percent sensitivity

- Standardized: computer-based and randomized, thus eliminating administrator error and memorization

- Quantitative: provide an, automatically calculated, precise score, not just pass/fail

- Defensible: policies tied to validated scores rather than outdated tools

If the FAA concluded that such measures are essential for pilots, whose work requires color-dependent safety decisions, then policing—where officers face split-second, life-and-death judgments—should adopt the same standard.

The Solution: High-Precision Testing & Annual Screening

Police agencies need to follow the FAA’s lead and modernize their approach to color vision evaluation. Importantly, the FAA grandfathered in existing pilots and will only be using the new screening for new job applicants.8 This will steadily increase mission readiness while ensuring current operations are not impacted.

Step 1: Implement validated, high-precision computer-based testing. Use the CAD, Rabin Cone Contrast Test, or Waggoner CCVT (WCCVT) for pre-employment screening.

Step 2: Re-test officers on a regular basis. Conduct annual screenings to identify acquired deficiencies that develop with age, disease, or exposure. Early detection matters not only for job performance but also for officer health—acquired deficiencies can signal glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, or other serious medical conditions.

Step 3: Educate officers. Provide education on how color vision differences may impact them, communication, and eyewitness testimony.

Benefits of validated, regular testing:

- Objective and repeatable: Standardized tests remove examiner bias and ensure consistent results.

- Fairer hiring: Instead of excluding all color-deficient candidates, agencies can set clear thresholds linked to job tasks.

- Job-task benchmarking: Systems like the Waggoner ColorSafe-LEO simulate up to 10 real police tasks, helping agencies determine who is fully qualified for duty and what cut scores to use on other color vision tests.

- Improved health care outcomes: Officers benefit from early detection of medical issues that impact vision. Tritan vision testing is the earliest ways to identify the top four leading causes of blindness (Age-Related Macular Degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and cataracts)., increasing early intervention and literally protecting officers from full blindness (not just color vision deficiencies).

By moving from outdated to modern, validated testing, agencies can raise safety standards and protect officers.

Legal and HR Considerations

Color vision standards are not just a medical issue—they are also a legal one. Hiring and retention decisions must be based on bona fide occupational qualifications, meaning agencies can only exclude candidates if deficiencies directly impair essential job tasks.

To ensure compliance and fairness, agencies should

- Conduct job task analyses: Tools like the U.S. Department of Labor’s O*NET database provide detailed analyses of the knowledge, skills, and abilities required for police and sheriff’s patrol officers (onetonline.org/link/summary/33-3051.00).

- Link deficiencies to specific tasks: For example, certain tasks like responding to red traffic lights during a pursuit, identifying blood evidence outdoors, or properly describing a suspect’s shirt color over the radio can be hindered by color vision deficiencies.

- Use modern test scores: By setting specific cutoff scores tied to validated tasks, agencies can ensure they are evaluating candidates fairly and defensibly.

This approach not only withstands legal scrutiny but also ensures agencies are hiring the best-qualified officers while safeguarding operational effectiveness and public trust.

Call to Action: Time to See the Danger

Color vision is more than distinguishing red from green. It impacts communication; situational awareness; evidence integrity; and ultimately, justice and safety. Outdated testing leaves agencies blind to these risks.

Police leaders must act now.

The stakes are too high to ignore. An officer’s testimony, a witness report, a missed bloodstain, or a misread signal light can mean the difference between justice and injustice—even life and death.

The FAA has already acknowledged this reality for pilots. It is time for more police agencies to improve their standards as well.

|

About Waggoner Diagnostics Waggoner Diagnostics is a leader in modern color vision testing, advancing how color vision deficiencies—commonly called colorblindness—are diagnosed and managed. Its flagship tool, the Waggoner Computerized Color Vision Test (CCVT), is FAA-approved and trusted by NASA, the U.S. military, and the FBI for its accuracy and regulatory compliance. Through TestingColorVision.com (TCV), Waggoner also delivers scalable, cloud-based testing that integrates seamlessly with Learning Management Systems (LMS), enabling organizations in healthcare, aviation, education, and government to test individuals remotely or in person. Founded in 1994 and headquartered in Bentonville, Arkansas, Waggoner continues to push the field forward with accessible, validated solutions that meet the demands of today’s occupational and regulatory environments. |

Notes:

1Barry L. Cole, “Assessment of Inherited Colour Vision Defects in Clinical Practice,” Clinical and Experimental Optometry 90, no. 3 (2007): 157–175.

2Nabeela Hasrod and Alan Rubin, “Defects of Colour Vision: A Review of Congenital and Acquired Colour Vision Deficiencies,” African Vision and Eye Health 75, no. 1 (2016): a365.

3Walter T. Delpero et al., “Aviation-Relevant Epidemiology of Color Vision Deficiency,” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 76, no. 2 (2005): 127–133.

4Douglas Joseph Ivan, “Ophthalmology,” in Rayman’s Clinical Aviation Medicine, 5th ed., Ed. Russell B. Rayman (Castle Connolly Graduate Medical Publishing, LTD, 2013).

5Jennifer Birch and Catharine M. Chisholm, “Occupational Colour Vision Requirements For Police Officers,” Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 28, no. 6 (2008): 524–531.

6Benjamin E. Evans, Marisa Rodriguez‐Carmona, and John L. Barbur, “Color Vision Assessment‐1: Visual Signals that Affect the Results of the Farnsworth D‐15 Test,” Color Research and Application 46, no. 1 (2021): 7–20.

7Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), “Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners: Application Process for Medical Certification – Examination Techniques, Item 52. Color Vision,” updated September 9, 2025.

8FAA, “Guide For Aviation Medical Examiners: Decision Consisders – Aerospace Medical Dispositions, Item 52. Color Vision,” updated August 27, 2025.