Photos by Tampa Police

All police agencies share common goals: to reduce crime and improve their community’s quality of life. Over the past several decades, agencies have become increasingly effective in applying proven approaches such as intelligence-led policing (ILP), community oriented policing (COP), and hotspot policing to achieve measurable reductions in crime.1 These approaches—when aligned with clear priorities and supported by organizational will—do more than move numbers on a dashboard. They change how a department looks, sounds, and feels to the community it serves.

Among these strategies, COP remains one of the most enduring and successful philosophies. It underscores the importance of community involvement in reducing crime and disorder. Research has credited COP with a 10 percent reduction in violent crime and a 37 percent increase in citizen satisfaction.2 At its core, community policing emphasizes partnerships with the community and collaborative problem-solving—coproducing safety by listening, acting, and staying accountable together.

As society evolves at a rapid pace, so too must community policing. Its future must continue to include compassion, inclusion, and meaningful engagement. When officers work alongside residents to address quality-of-life concerns, they not only build safer neighborhoods but also develop a sense of belonging and pride in the communities they serve. As Sir Robert Peel, the father of modern policing, observed more than a century ago: “The police are the community, and the community are the police.” That principle endures as a guiding light, reminding today’s police and community members that legitimacy and effectiveness can only be achieved together.

True community policing occurs when officers treat the neighborhoods they patrol as if they were their own. In major cities, patrol districts vary in demand and desirability, yet the most compelling examples emerge when senior officers choose to remain in more challenging areas because of the relationships they have built with the community. When that dedication is combined with problem-solving that addresses the root causes of crime, a powerful synergy emerges that reduces crime while strengthening trust.

For problem-solving to be effective, officers must recognize the social, health, and quality-of-life issues that intersect with crime. They must also identify and address hotspots—micro-places where harm concentrates. Unlike traditional reactive models, community policing asks officers to slow down deliberately: spend time at calls, engage with residents, loop in partners, and work proactively to prevent future problems rather than simply moving from incident to incident.

Tampa’s Focus on Four

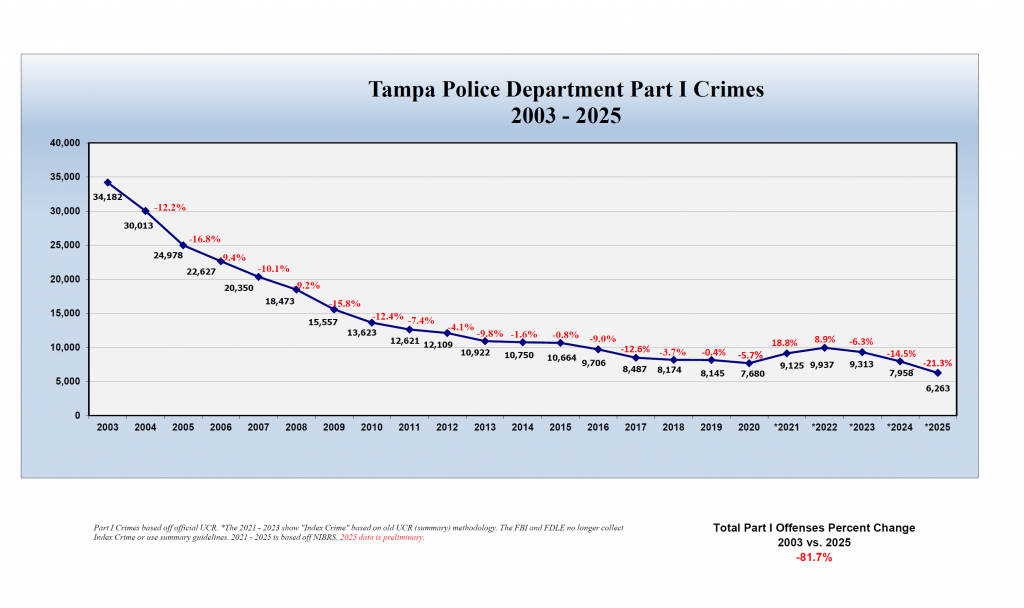

In the early 2000s, Tampa, Florida, faced rising crime and declining trust. The Tampa Police Department (TPD) responded with its Focus on Four plan, targeting auto burglary, auto theft, burglary, and robbery—offenses closely tied to violence and future crimes.3 The logic was straightforward: stolen guns often come from auto burglaries; stolen cars are frequently used to commit more serious offenses; robbery is a strong predictor of future violence; and burglary corrodes neighborhood stability. By concentrating on these crimes, the department aimed to reduce not only incidents but the conditions that incubate more serious harm.

Guided by the Focus on Four principles of ILP, data-driven resource allocation, proactive and preventive policing, and community policing, the city achieved nearly an 80 percent reduction in crime over two decades. This success helped restore confidence both inside the department and across communities. The Focus on Four became the foundation for a healthier public safety ecosystem where officers, analysts, residents, and local partners worked from the same playbook.

ILP drives the daily tempo of Focus on Four. Analysts translate raw data into actionable patterns; supervisors shape deployments based on those patterns; and officers pair visibility with engagement at places where harm clusters. Tactical reallocation allows the department to move resources at the speed of the problem—surging patrol, street crime, or specialized units to emerging hotspots and then tapering as conditions change. Proactive and preventive policing encourages officers to initiate activity—knock on doors, check on juvenile probationers, call apartment managers, walk the lot with business owners—rather than waiting in their patrol cars for the next call. And community partnership ties it all together by ensuring the people who live with a problem help define the solution.

Culture, Mission, and the Power of Clarity

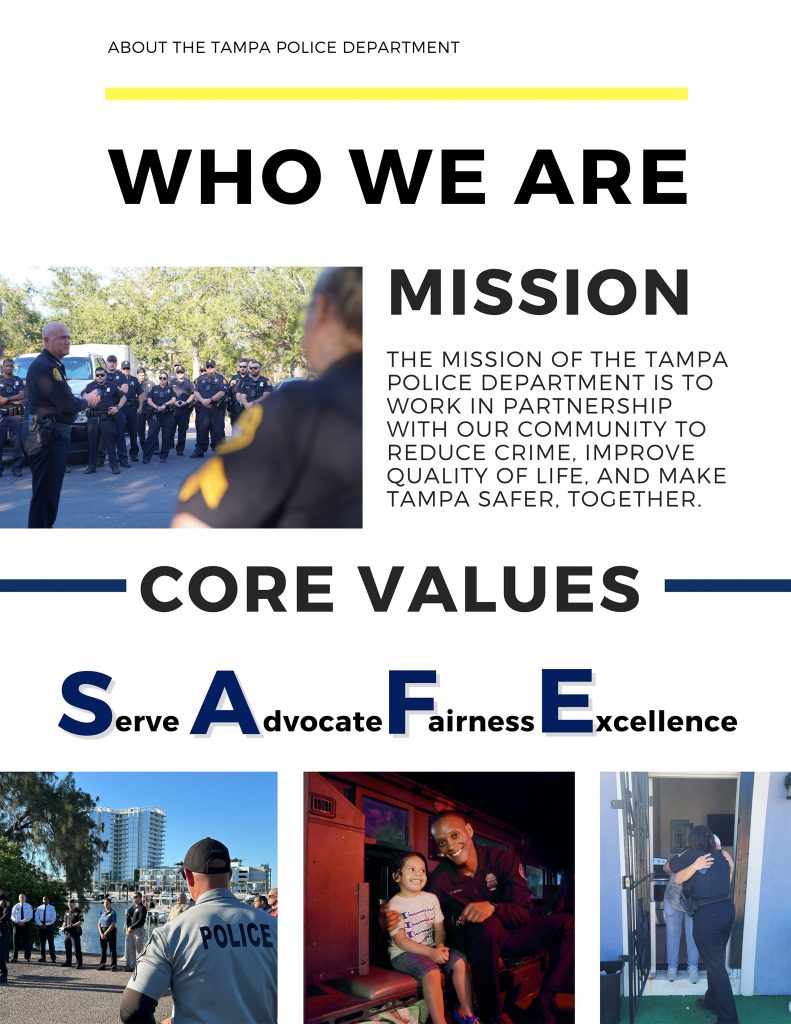

Community policing has to be more than a good idea; it must be embedded in a department’s culture and mission. In 2003, TPD adopted a mission statement that is community-centered, actionable, and succinct:

“The mission of the Tampa Police Department is to work in partnership with our community to reduce crime, improve the quality of life, and make Tampa safer, together.”4

The clarity of this statement matters. By aligning daily decisions with a shared mission—and by reinforcing that mission at roll calls, command meetings, community events, and public briefings—the department underscores that community policing is not merely a program; it is the guiding philosophy behind everything the department does.

Addressing Fear of Crime

Reducing crime is essential. Addressing the fear of crime is equally important. TPD has long emphasized this dual mission by inviting ongoing feedback and making engagement measurable.

Recently, the department introduced an automated survey tool connected to the computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system. People receive real-time text notifications if officers are delayed due to higher-priority calls and, at the conclusion of service, they receive the case information and a brief survey that allows residents to evaluate the officers’ professionalism and communication, their overall experience with the department, and their sense of safety. The early results have been overwhelmingly positive, and just as important, the feedback loop gives TPD a living barometer of trust. The department now has a structured way to hear from people who rarely attend community meetings—voices that traditional outreach can miss.

This same commitment to blending accountability with support is visible in TPD’s juvenile probation checks. Rather than relying solely on the Department of Juvenile Justice for curfew/home detention checks, patrol officers conduct visits for repeat juvenile offenders in their assigned neighborhoods. Officers get to know the youth and their families. Sometimes that means backing up a single parent who needs help with accountability; sometimes it means enforcing a curfew violation as a probation arrest. Either way, the message is consistent: the department cares enough to show up—and follow up. This combination of presence and consequences drove down youth-related auto burglaries and auto thefts, and more importantly, reframed relationships between officers, families, and schools.

Leadership, Evaluation, and Incentives

Community policing will not survive as only a slogan. It must be reinforced through leadership expectations, evaluation systems, and incentives. At TPD, middle and upper management are expected to measure what matters and recognize what works. Supervisors measure outcomes (e.g., problem-solving efforts, community meetings, front porch roll calls, and other community policing efforts). Officers are expected to spend adequate time on each call, identifying root causes rather than addressing only the immediate symptom. Foot and bicycle patrols—especially in hotspots and around community assets like schools, parks, and apartment complexes—are built into deployment plans to increase visibility and familiarity.

Kappeler’s Eight-Step Framework in Practice

Like many agencies, TPD’s community policing efforts were strained by the COVID-19 pandemic and a broader decline in public support for policing. Social distancing discouraged engagement; community meetings were halted; and neighborhood watch groups dissolved. As crime rose, agencies across the United States re-evaluated the best practices.

After the COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread decline of trust in police, TPD revitalized its COP philosophy by applying Kappeler’s eight-step framework from Community Policing: A Contemporary Perspective.5 This framework served as a stabilizing spine during a period of national turbulence and local reassessment.

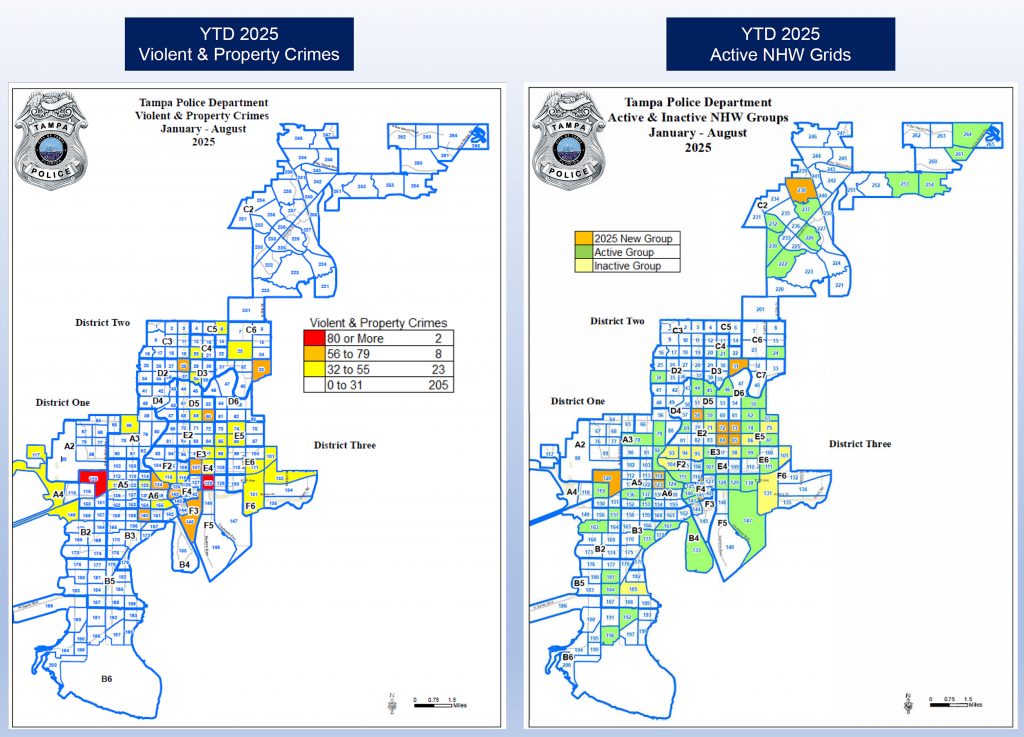

Step 1: Identify performance gaps with transparency. The department took a hard look at where COP had challenges: inactive neighborhood watch groups, fewer officer-led community meetings, and reduced engagement beyond calls for service. Analysts overlaid watch group activity on crime maps to identify areas where participation was weak or had dissolved altogether.

Step 2: Recognize the need for change. As call loads and external pressures mounted, officers had gradually reverted to traditional, less engagement-driven practices. Leadership reset priorities toward engagement and problem-solving, starting with the most impacted neighborhoods.

Step 3: Demonstrate optimism and leadership commitment. Leaders modeled visible belief in COP, reinforced by the chief’s professional and academic background and a clear recommitment. Optimism was not rhetorical; it was operationalized, with time, resources, and accountability attached.

Step 4: Address barriers and educate officers. Training emphasized that COP is central to the mission, not a side project. Command staff highlighted successful case studies at CompStat and roll calls, demystifying what “good” looks like: an officer’s patrol that led to a property manager installing better lighting; a bike patrol that connected teens to late-night recreation; a follow-up on a nuisance call that turned into a mediated agreement among neighbors.

Step 5: Identify alternative strategies. The department retrained supervisors and reintroduced recognition programs—including a Community Policing Officer of the Month award and internal spotlights—so that officers saw their efforts reflected back in tangible ways. Externally, success stories were shared through mainstream media, social media, and community newsletters to normalize partnership-based policing.

Step 6: Select the appropriate strategy. TPD made revitalization department wide. Patrol, investigations, and support units were expected to integrate COP principles rather than outsource community relations to a single unit.

Step 7: Develop a comprehensive implementation plan. The department restructured command responsibilities and at the time created a deputy chief position dedicated to COP. CompStat categories were expanded to include community meetings, foot and bike patrols, front porch roll calls, and de-escalation techniques. Neighborhood watch participation was layered onto crime mapping to show, visually, how social guardianship and crime trends intersect.

Step 8: Evaluate and modify the strategy. COP is iterative, not static. The department used CompStat and CAD survey responses as living metrics, adjusting tactics, sharing what worked across districts, and revisiting problems until durable improvements were achieved.

The department responded by returning to the eight-step framework—not as a checklist, but as a change process. Leadership chose to amplify trusted voices. A retiring union president—an officer with deep community roots—recorded a department-wide video describing her sense of belonging, the neighbors she knew by name, and the tangible improvements she had witnessed over a career spent close to the community. Her testimony sparked others to share their own experiences, and the effect was contagious: story by story, the rank and file helped re-author the department’s identity.

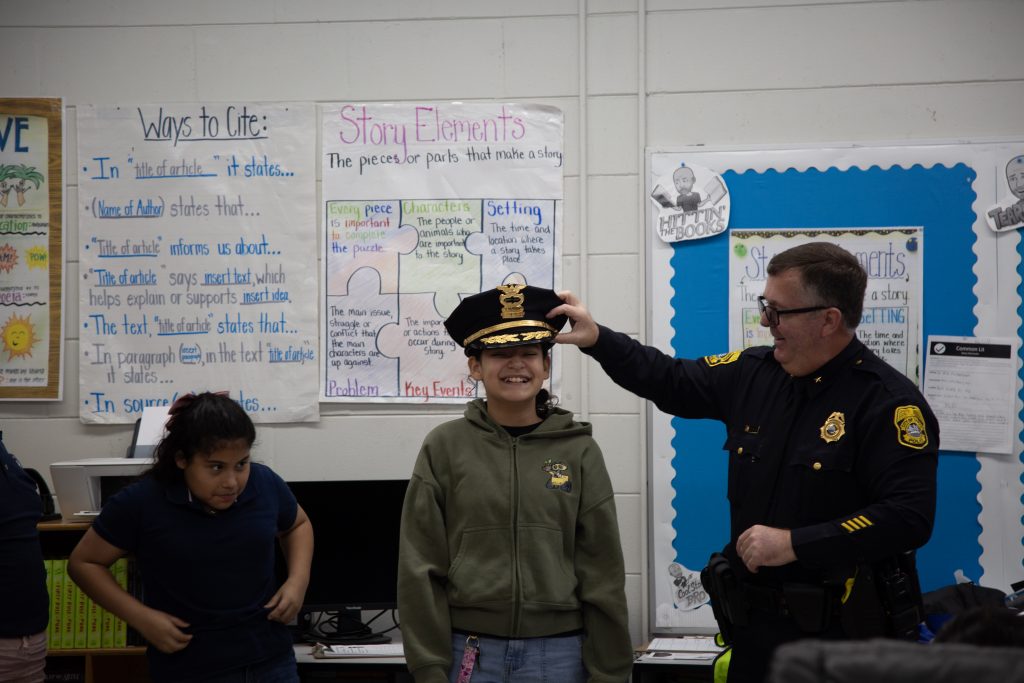

TPD then reintroduced COP with a visible and sustained push. Supervisors and commanders were retrained on COP principles with emphasis on how to coach problem-solving. Officers’ stories of everyday service—showing children how fingerprint powder works, mowing a neglected strip of grass that blocked sightlines at a bus stop, replacing a burglary victim’s porch light, and leaving personal contact information—were shared across platforms. These small acts, repeated daily, changed the thermostat of trust. They also reinforced that COP is every officer’s responsibility, not confined to a specialized unit’s portfolio.

Youth Outreach as a Cornerstone

TPD’s revitalized philosophy leveraged long-standing youth programs and expanded them to meet today’s needs.6

RICH House (Resources in Community Hope). In 2000, TPD converted a former drug house in Sulphur Springs into a safe haven for youth. Officers served as positive role models and tutors, and the house became a daily presence of stability in the neighborhood. In 2013, a second RICH House opened in Robles Park. One particularly powerful story came full circle when a child who once relied on the program later returned as a TPD officer assigned to the very house that helped shape his future.

Bigs in Blue. In 2017, TPD partnered with Big Brothers Big Sisters of America to launch Bigs in Blue, pairing officers with youth for one-on-one mentoring at school. Thirty-five officers volunteered at the start, and the results were immediate: students gained advocates who could navigate both school and neighborhood realities; officers gained a deeper understanding of the children and families they served.7 These relationships became a quiet engine of prevention by helping kids solve problems upstream.

Police Athletic League (PAL). Revitalized in 2023, PAL expanded traditional sports to include boxing, along with extended stay-and-play hours during school breaks. The Friday Night Midnight Basketball program offered structured recreation and mentorship precisely when youth are most at risk for victimization or offending. Coaches and officers worked side by side, turning exercise into pro-social connection.

Shielding Our Teens. In partnership with the state attorney’s office and local businesses, TPD launched Shielding Our Teens, a three-week mentorship and job-readiness program that paired nearly 100 high school students with officers and community partners. Students learned how to prepare for interviews and secure summer employment, which many did. In one case, a patrol officer conducting a 9:00 p.m. curfew check connected a teen to the program, thus leading to their employment and a network of adult supporters.

Together, these programs show that community policing is not a single tactic but an ecosystem of relationships. The unifying lesson: when officers and youth meet long before a crisis, both are changed by the encounter.

Implementation and Accountability

To translate philosophy into performance, TPD aligned structure, metrics, and incentives. The creation at the time of a deputy chief for community policing signaled that COP is core business. CompStat reviews were expanded to capture the work that often goes unseen: foot and bike patrols, front porch roll calls, community meetings, crime prevention through environmental design improvements, de-escalation techniques, and neighborhood watch activity. Analysts overlaid neighborhood watch group status on crime maps so commanders could see instantly where social guardianship was strong, where it was waning, and where outreach was needed.

The automated CAD survey added a second lens: near-real-time feedback from people who had recently interacted with officers. Supervisors now had a tool to coach communications, set expectations, and celebrate excellence. Patterns in survey comments helped identify where information flow needed adjustment (for example, when an arrival delay was unavoidable, how the situation was explained to residents mattered) and where service exceeded expectations.

Measurable Results

The outcomes of TPD’s revitalized community policing have been clear and sustained:

- 2023 Annual Report: TPD recorded a 7 percent reduction in total crime, an 8 percent reduction in violent crime, and a 17 percent reduction in violent crime with a firearm. Use of force incidents decreased by 6 percent, while de-escalation increased by 10 percent.8

- 2024 Annual Report: The department reported an additional 15 percent reduction in total crime, an 8 percent reduction in violent crime, and an 18 percent reduction in violent crime with a firearm. Use of force fell another 11 percent, while de-escalation increased by 18 percent.9

- 2025 Outcomes: Crime continues to decline with homicides down over 40 percent and reduced to the lowest levels in over half a century. Moreover, all violent crime and property crime also continues double-digit percentage reductions.

Just as important, the CompStat neighborhood watch overlay demonstrated growing participation across sectors, highlighting neighborhoods where commanders and community leaders strengthened watch groups and expanded guardianship. in addition, the automated CAD surveys consistently showed high marks for officer professionalism, department responsiveness, and perceived safety—giving the city confidence that the numbers on crime reports were matched by improvements in how people feel.

Lessons for Other Agencies

Several principles from TPD’s experience are portable to other jurisdictions:

- Pick the right levers. Focus on offenses that drive violence and disorder downstream. Tampa’s Focus on Four aligned tactics with offenses that set the stage for more serious harm.

- Make engagement measurable. If foot patrols, community meetings, and de-escalation matter, put them on the CompStat report. What is measured grows.

- Use stories to move culture. Data inform; stories inspire. Amplify officers who personify problem-solving and service. Recognition programs, internal videos, and community spotlights turn good work into a shared identity.

- Close the loop. CAD surveys and community meetings are not endpoints; they are engines for continuous improvement. Tell residents what was heard and what was changed as a result.

- Build youth pipelines. Programs like RICH House, Bigs in Blue, PAL, and Shielding Our Teens show that mentorship, structure, and opportunity are the best inoculations against harm.

- Align structure with strategy. A deputy chief dedicated to COP, expanded CompStat metrics, and neighborhood watch map overlays ensured that what the department valued became what it consistently did.

Looking Ahead

Community policing will continue to evolve as cities change, and expectations rise. In Tampa, the next phase includes enhancing partnerships with schools, faith organizations, neighborhood associations, and local businesses; strengthening transparency around survey results and community metrics; and continuing to refine deployment with problem-solving and community policing at the center. The goal is not a short burst of success but a durable capacity to keep listening, adapting, and serving.

Conclusion

Community policing is more than a philosophy—it is at the heart of the department’s identity. It is about building trust, creating lasting connections, and ensuring every resident feels seen and valued. When officers go above and beyond, the result is stronger relationships, safer neighborhoods, and a deeper sense of shared responsibility between police and the public. The evidence is clear: consistent, personal engagement enhances community cohesion and strengthens trust. For TPD, community policing is not just a strategy, it is a philosophy and culture woven into the heartbeat of the organization that has driven measurable crime reductions while reinforcing legitimacy, trust, and pride between officers and the community they proudly serve. d

Notes:

1Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), Reducing Crime through Intelligence-Led Policing (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2012).

2Jeremy G. Carter and Bryanna Fox, “Community Policing and Intelligence-Led Policing: An Examination of Convergent or Discriminant Validity,” Policing: An International Journal 42, no. 1 (2019): 43–58.

3BJA, Reducing Crime through Intelligence-Led Policing.

4Tampa Police Department, Annual Report 2024: A Year of Resiliency (Tampa Police Department, 2024).

5Victor E. Kappeler and Larry K. Gaines, Community Policing: A Contemporary Perspective, 6th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2011).

6Tampa Police Department, “TPD Programs.”

7Big Brothers Big Sisters of Tampa Bay, “Bigs in Blue/Bigs with Badges.”

8Tampa Police Department, 2023 Annual Report (Tampa, FL: Tampa Police Department, 2023).

9Tampa Police Department, Annual Report 2024: A Year of Resiliency.

Please cite as

Lee Bercaw, “Community-Focused Problem-Solving: Lessons from Tampa’s Revitalization and Results,” Police Chief Online, January 21, 2026.