Across the landscape of police wellness, there is a critical missing piece when it comes to supporting those who serve and protect.

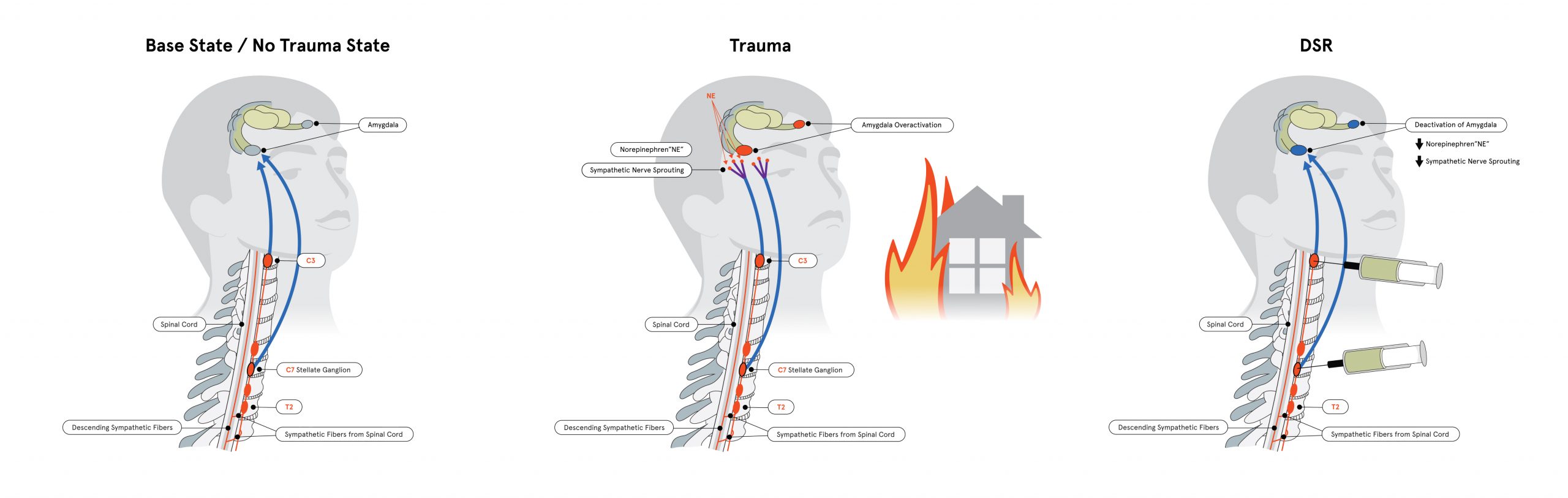

The missing piece is this: Just as multiple head injuries create biological changes associated with post-concussive syndrome, multiple trauma exposures cause biological changes that alter the functioning of the fight or flight system.

As of this publication, New York University (NYU) is conducting a landmark study looking at how trauma changes the brain, using pre-and post-trauma fMRI brain scans. The study aims to show that trauma can not only be seen with the right brain scan, but that trauma-driven brain injuries can also be healed with innovative treatment that is now available.1

Police officers incur multiple traumas across the course of a typical career. In a sample of more than 700 police officers from three major departments, about a quarter had seen a fellow officer be injured or killed in the line of duty, over half had been threatened with a deadly weapon, and nearly all (87 percent) had seen someone die.2

This chronic trauma exposure alters the body’s fight-or-flight system. Specifically, individuals lose their ability to flip the switch back to “calm.” Military veterans and first responders often describe themselves as living in a state of chronic threat response. They say they feel like a muscle car that can’t throttle back to neutral. Many of them identify with the characterization that their fight-or-flight system has become a “hair trigger” nervous system that goes from relatively calm to overdrive in no time at all, even when there is no clear and present threat.

Impacts of Overactive Fight-or-Flight System

There are predictable biological changes associated with this altered state. Those living with chronic trauma can’t sleep. They often say they get only about three to four hours of good sleep per night. They feel continually irritable, even with those they love, like their children and significant others. They can’t concentrate. They may have trouble reading a book, even one they find interesting.

This altered state, this injury to the fight-or-flight system, is associated with several critical components of quality of life, as well as police officer career satisfaction and retention.

Here are four things which are profoundly affected when the fight-or-flight system is in continual overdrive.

1. Interactions with the public.

When somebody is calm in their own body, they approach new situations from a neutral stance. They tend to be open, assessing all information from their environment without a particular slant. The human capacity for curiosity flows from a relaxed and open state of mind.

Conversely, those with an over-activated fight-or-flight system tend to see novel situations and unfamiliar people as a “threat” more quickly. When information is limited, the mind fills in the blanks. The mind does this not only based on past experiences but also based on the immediate physiological state a given individual experiences in the context of a novel situation.

“Techniques and resources can help, the hard truth is that some first responders and military veterans get to a point where they no longer have control of their nervous system”

When the body and mind perceive a state of threat, tunnel vision takes over. In medicine, there is even a term for this. “Foveal vision” involves actively scanning environments from the front part (fovea) of the eye. While tunnel vision can dramatically increase line-of-sight visual acuity, information in the peripheral visual array is lost. The loss of this peripheral feedback may include information that runs counter to the default assumption that an unknown person is a potential threat. In addition, people who feel under threat lose much, if not all, of their capacity for empathy and compassion.

It’s hard enough for two humans to read each other’s unspoken intentions in the best of circumstances. It’s even harder when one person has a dysregulated fight-or-flight system. And when two people in an interaction are in chronic threat response mode, this heightens the chances that things will go sideways. In this hyper-activated state, the interaction can easily become a “you versus me” situation versus a “how can we” situation.

2. Interactions between leaders and teams.

Police officers who are in a continuous state of fight-or-flight overdrive are also more likely to misperceive the intentions of their leaders.

Instead of viewing a given situation from a neutral stance, those who live in a continuous state of heightened nervous system arousal perceive threat more readily and by default. Anytime there is a critical incident, there are mandatory investigations, policies, and procedures that must be initiated. The aftermath of any critical incident is a high-stakes time for all involved. The handling of the incident between leadership and involved officers opens multiple new portals to perceived ruptures in trust between administrative leaders and members of the department.

Following critical incidents, there are layers of complicating factors. For example, does a given leader understand that what they say or don’t say in these critical moments can determine a police officer’s perception of support or betrayal? The silence of leaders, in the context of media misrepresentation, can be felt as the biggest betrayal for police officers.3

Even when there is insight on the part of a police chief, an officer with a dysregulated fight-or-flight system is more likely to perceive betrayal at any number of junctions in the process of being investigated or put on routine administrative leave.

“Engaging in therapy with a culturally competent provider with whom the officer feels a sense a trust can help regulate the fight-or-flight system”

At the IACP 2024 conference in Boston, Massachusetts, a group of police leaders shared that unrelenting—and often contradictory—administrative pressures can impact the nervous system as much as multiple trauma exposures during a patrol shift. One well-respected chief said that he had seen hundreds of traumas over his career, including several baby deaths, and the perpetual dread of knowing that one of his team could be hurt or killed in the line of duty at any time, day or night, has been harder for him than any other trauma. Several emphasized that there is no end of shift or pressure relief for chiefs who care deeply about their people.4

This makes it critical for police chiefs and those they lead to pay attention to the functioning of everyone’s fight-or-flight system, including their own.

3. Relationships at home.

As mentioned, people who have a dysregulated fight-or-flight system can’t sleep. And when one person is tossing and turning, waking up in a cold sweat, getting disrupted sleep, or sleeping in a separate bedroom to protect their partner, this absolutely impacts their significant other.

Being in a state of chronic stress may contribute to rapid mood changes that can leave the person’s family members feeling like they’re walking on eggshells. Spouses of military veterans and first responders can develop secondary post-traumatic stress symptoms from living in this context.5

In a chronic state of threat, individuals often flip between overwhelmingly intense emotions and feeling numb. Emotional numbing stunts the ability to have warm, loving feelings for family members and trusted friends. A decreased capacity for empathy and compassion also impacts the depth of emotional relationships with partners and children. Chronic hypervigilance can lead individuals to “bunker down” and stay home, avoiding large social gatherings, which can impact the entire family’s quality of life. And when family life becomes strained, this adds weight to the invisible rucksack that first responders carry into their day-to-day work

4. Suicide risk.

Finally, a critical, largely unrecognized, connection exists between a dysregulated fight-or-flight system and suicide risk. Protectors and defenders are capable of weathering many storms. They are resilient by nature. However, they also have a unique Achilles heel, a vulnerability that often hides in their blind spot.

This unique vulnerability comes from the fact that first responders (just like military service members) are wired and trained to protect others—and repeatedly reinforced to minimize their own individual needs in support of the greater good. Therefore, when they start to feel like they’re “broken” and helpless to regain control in their own body, they may quickly become at risk for suicide.

And if they find themselves yelling at their kids or the spouse they love and they see a look of fear on their faces, they are at risk for believing a lie that often drives suicidal behavior among first responders—that they are the problem that needs to be eliminated. Further, because police officers are trained to eliminate threats and defend the defenseless, they may move with purpose on this perceived threat to their family’s future well-being.

There is much more depth to this picture that needs to be better understood within the policing community, but one critical missing piece of this tragic cascade tracks back to a continually over-activated fight-or-flight system. Research backs this up. Researchers who tracked the psychological, psychophysiological, and behavioral features characterizing a suicide attempt as it unfolded in real-time, observed continuously heightened sympathetic nervous system arousal leading up to suicide attempts.6

Strategies to Address a Dysregulated Nervous System

There are a number of strategies that can help.

The lowest level of intervention is daily practices geared toward calming the nervous system. One method that has crossed over from the military to first responder circles is “box breathing.” First developed for use by Navy SEALS, box breathing involves breathing in for a count of four, holding one’s breath for a count of four, breathing out for a count of four, and holding for count of four before taking the next breath. Intentional rhythmic breathing that draws oxygen deep into the body can help slow down and restore stasis to the nervous system.

A second intervention comes from an observation of powerful work done by an organization called Operation Freedom Paws (OFP). The founder of OFP, Mary Cortani, is a brilliant canine handler who served in the U.S Army in this role. She now pairs veterans and first responders with therapy dogs and trains them to work together as a seamless team. She also selects and trains therapy dogs to serve entire departments.7

As part of the canine-handler bonding process, Cortani facilitates a particular exercise that has real potential to help regulate the fight-or-flight system. This requires a dog—any dog that an individual has a bond with, whether the dog is theirs or their department’s canine, will serve.

Here’s the exercise.

The individual sits in a recliner and invites (or lifts) the dog to lay on their chest. They then tune into the dog’s physiological state. They are instructed to focus attention on the dog’s heart rate, breathing, and muscle tone. They then use their body to bring the dog to a calm and relaxed state.

Focusing on getting a dog to relax can be a uniquely helpful exercise for protectors and defenders. It’s much easier (and wiser) than telling anyone to “just relax.” Because police officers are wired to be externally focused, this tendency can be used to good effect with a dog. And when they get the dog’s body calm, their own bodies will most likely be in a calmer state too.

A similar exercise can work wonders with the trusted humans in an individual’s life, but it may be easier for some to first practice with a dog (as long as there is a level of familiarity and comfort with the dog). It can be challenging at first for those in an overactive state to tolerate lengthy, relaxed body contact. But this is precisely what many first responders and their spouses need to hold a close and loving bond. Research backs this up: the touch of a loved one can help regulate the fight-or-flight system.8

A variant of this principle emerged in a personally memorable clinical scenario. Usually, psychologists don’t get to see what’s on the inside, relying instead on external cues and what people say. In this scenario, though, one of my patients was in the operating room about to receive a treatment that sounded like it came straight out of science fiction. A former special forces medic, he was receiving an injection into a cluster of nerves in his neck, a nerve block procedure used for over one hundred years to treat pain and has the potential to effectively treat the symptoms of a dysregulated fight-or-flight system.

As my patient mentally prepared for the procedure, his heart rate suddenly shot up. Because he was hooked up to a heart rate monitor, the change in his fight-or-flight function was audible in the room. The use of voice and the gentle but firm pressure of my hand on his ankle helped him lower his heart rate very quickly in real time. It was a powerful example of how the touch and presence of someone an individual trusts can help regulate the nervous system.9

Engaging in therapy with a culturally competent provider with whom the officer feels a sense a trust can help regulate the fight-or-flight system. Having a totally safe and confidential place to talk about the things that create feelings of threat releases these elements from bouncing around like wrecking balls in the psyche.

While these techniques and resources can help, the hard truth is that some first responders and military veterans get to a point where they no longer have control of their nervous system. They can’t downshift their fight-or-flight system, even with these techniques and exercises. In special forces operators, the same phenomenon is often observed. Special forces operators in this situation can receive a procedure called stellate ganglion block (SGB), as described briefly in the case of the special forces medic, which can help restore calm and control to the fight-or-flight system.

SGB involves injecting a numbing medication, a widely used FDA-approved anesthetic, typically ropivacaine or bupivacaine, into the cluster of nerves a few inches above the collarbone. In today’s rapidly evolving treatment landscape, first responders, veterans, and civilians may receive an advanced form of SGB that involves two injections into two clusters of nerves, which has been associated with better outcomes in peer-reviewed published data.10

SGB involves injecting a numbing medication, a widely used FDA-approved anesthetic, typically ropivacaine or bupivacaine, into the cluster of nerves a few inches above the collarbone. In today’s rapidly evolving treatment landscape, first responders, veterans, and civilians may receive an advanced form of SGB that involves two injections into two clusters of nerves, which has been associated with better outcomes in peer-reviewed published data.10

Clusters of nerves in the neck, called “ganglia,” are associated with sending signals to the rest of the body that keep the body in a state of chronic threat or relative calm. By numbing these nerves, SGB soothes and reboots the system. SGB is a go-to treatment in several special forces units and is frequently used at major U.S. military facilities and hospitals, including Tripler Army Medical Center, Walter Reed Medical Center, Womack Army Medical Center, and Landstuhl Regional Medical Center.11

When applied in active-duty military contexts, SGB is used between deployments to restore calm and control as a performance enhancer. Specifically, research shows that SGB actually improves operators’ cognitive performance and response time.12 It follows that the same would be true for police officers.

In other words, SGB does not prevent a protector from responding to a real threat. With the nervous system regulated in a healthy way, an individual can better discern what is actually a threat and then respond even more quickly when a threat is real.

Conclusion

As this article has highlighted, a chronically dysregulated nervous system can change everything in the life of police officers—their interactions with the public, their conversations with colleagues and feelings about department leaders, their relationships with loved ones, and even their level of suicide risk. Yet, because police officers are professionally good at compartmentalizing their suffering, this kind of injury can be invisible, not just to others, but to the officers themselves. This is where changing the frame to a peak performance model becomes critical. In the special operations community, there is no stigma associated with having one’s fight-or-flight system reset between combat deployments. This kind of procedure is a natural extension of the demand for these operators to perform at their highest capacity. So, they are trained to be aware of the indicators of suboptimal nervous system functioning—things like sudden panic attacks, fractured sleep, and unexpected flashes of anger. (And when operators fail to detect these signs, their spouses often send them for treatment!)

The author’s experience as a healer within both communities has made it clear that police officers are equally or more impacted by trauma exposures than those who serve in the special operations community. When self-regulation strategies aren’t able to restore calm and control to the nervous system, it is critical that police officers gain access to the most effective, innovative treatments available to restore them to peak performance, and avert the potential for tragic outcomes.

Notes:

1NYU Langone Health, Effects of Stellate Ganglion Block in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT05391971), updated February 2, 2025.

2Daniel S. Weiss et al., “Frequency and Severity Approaches to Indexing Exposure to Trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for Police Officers,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 23, no. 6 (2010): 734–743.

3Shauna Springer, “Administrative Betrayal: Why the Silence of Leaders Is the Greatest Trauma for Many LEOs,” Police1, February 14, 2024.

4Shauna Springer, “The Unseen Toll of Leadership: Chiefs Speak Out on the Human Cost of Command,” Police1, March 22, 2025.

5Matthew Hill, Jessica Paterson, and Amanda Rebar, “Secondary Traumatic Stress in Partners of Paramedics: A Scoping Review,” Australasian Emergency Care 27, no. 1 (2024): 1–8.

6Daniel Coppersmith et al., “Real-Time Digital Monitoring of a Suicide Attempt by a Hospital Patient,” General Hospital Psychiatry 80 (2023): 35–39.

7Operation Freedom Paws, “About Us.”

8Monika Eckstein et al., “Calming Effects of Touch in Human, Animal, and Robotic Interaction—Scientific State-of-the-Art and Technical Advances,” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (2020).

9Shauna Springer, “Women In Wellness: Shauna Springer of Stella on the Five Lifestyle Tweaks That Will Help Support People’s Journey Towards Better Wellbeing,” interview by Wanda Malhotra, Authority Magazine, November 12, 2023.

10Eugene Lipov et al., “Utility of Cervical Sympathetic Block in Treating Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Multiple Cohorts: A Retrospective Analysis,” Pain Physician 25, no. 1 (2022): 77–85.

11Shauna Springer et al., “Optimizing Clinical Outcomes with Stellate Ganglion Block and Trauma-informed Care: A Review Article,” NeuroRehabilitation 55, no. 3 (2024): 385–396.

12Sean Mulvaney et al., “Neurocognitive Performance Is Not Degraded After Stellate Ganglion Block Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Case Series,” Military Medicine 180, no. 5 (2015): e601–e604.

Please cite as

Shauna Springer, “Fight or Flight in Overdrive,” Police Chief Online, May 14, 2025.