Every day, police officers around the world encounter individuals in crisis. Unfortunately, some of these individuals are military veterans suffering from unique challenges associated with their service to their nation. The Military Veterans Wellness Program (MVWP), a groundbreaking initiative developed by the Toronto Police Service, has revolutionized how police personnel interact with and support this vulnerable population to whom so much is owed. This program is not just a toolkit; it’s a lifeline that saves lives, restores dignity, and sets an international standard for veteran support. The MVWP aligns with the ideals of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) by fostering global collaboration and sharing best practices for de-escalation and improving public safety. The MVWP is also free for any law enforcement agency, and the Toronto Police Services MVWP has partnered with the IACP to make this valuable training to all IACP members through the IACP Learn platform, courtesy of Toronto Chief of Police Myron Demkiw, board member and vice chair of the IACP Global Policing Division, reinforcing the critical mission of protecting the protectors. Veterans should not fall through the cracks of society, and the police, in their unique position, are ideally situated to help support those who serve our nations during their time of need.

Armed forces members from around the globe endure demanding training and can be called upon to undertake some of the most challenging and perilous operations anywhere in the world. This commitment requires courage and sacrifice to answer a nation’s call, whether that call is for combat operations, disaster relief, or any other task of national importance. These warriors safeguard national security, promote global stability, and ensure the well-being of those in need. This type of service can come at a profound cost to individuals and families. The rigorous training and intense, sometimes traumatic experiences can leave lasting impacts on those who serve. Armed forces members are released from the military and enter civilian life, becoming veterans for a variety of reasons, at times not by their choosing. This transition period can be accompanied by significant losses to the individual in areas such as camaraderie, life structure, job security, steady income, skill appreciation, excitement, travel, sense of purpose, and fitness. Beyond the feelings of loss, many veterans and their families can experience multifaceted challenges as they navigate a new career, find health support, adjust to a new identity, make financial adjustments, deal with relationship stress, and adapt to civilian life. Of those veterans who have experienced combat, 75–80 percent transition very successfully to civilian life, even though they experience these losses. To successfully transition, veterans need to be supported in many ways.

In Canada, veterans can receive significant support from Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC), the Royal Canadian Legion (RCL), and Operational Stress Injury Social Support (OSISS). These three veteran social services, when they work together, are not perfect, but many consider them the most generous in Canada.

Although these social services continue to improve, Canadian veterans can encounter significant challenges that make their transition difficult, many of which also apply to veterans of other countries.

- Logistical Challenges: Many veteran benefits require lengthy paperwork from limited public health care providers who lack knowledge of veteran services. This often causes significant delays, prevents care, or even provokes a veteran to stop trying to receive support due to administration fatigue.

- Cultural Incompetence: Because of a lack of education, public health care providers often lack insight into the unique needs of veterans. Conditions like military-related post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and chronic musculoskeletal injuries are frequently mismanaged or overlooked.

- Gender-Specific Issues: Female veterans face distinct challenges, including higher rates of military sexual trauma and a more difficult time reintegrating into civilian life.

- Social Stigma Challenges: It is complicated for a veteran to transition from being the “helper” to the “helped,” especially when military training reinforces the ideals of being a protector, never quitting, and pushing through the pain.

These systemic shortcomings and challenges, although improving, leave some veterans in Canada vulnerable to experiencing untreated physical and mental health conditions, which can result in further social problems.

The Consequences of Inaction

Accepting the current status quo has profound implications for veterans struggling to transition to civilian life. Insufficient access to culturally competent health care and a lack of integration across sectors—such as police, health care, and social services—can lead to these problematic outcomes, among others:

- Canadian veterans are at higher risk of suicide and homelessness when compared to the general population.

- Veterans’ interactions with police tend to be more violent and dangerous, which may be prevented with earlier intervention.

- Veterans contribute to higher societal costs, including emergency department visits, incarceration, and strained resources across multiple sectors.

The Desmond Fatality Inquiry in Nova Scotia highlighted the tragic consequences of systemic failures. In 2017, Lionel Desmond—a veteran of the war in Afghanistan—took his own life after killing his mother, wife, and 10-year-old daughter. The inquiry revealed the devastating impact of insufficient access to culturally competent care and inadequate interagency collaboration. For public safety, the message is clear: When veterans fall through the cracks, the consequences can be catastrophic. However, police officers are perfectly positioned to be the conduit for de-escalating and influencing a veteran to accept help and not fall through the gaps.

Closing the Gaps with Lived Experiences

The Toronto Police Service is the largest municipal police service in Canada, with more than 7,000 employees, serving more than 5 million people across Toronto. Constables Aaron Dale and Jeremy Burns, who were hired in 2018, are military veterans and recognized the gaps veterans fall into firsthand because of their own struggles following military service. Constable Burns, an infanteer with Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, deployed to Afghanistan, where several members of his tour were lost overseas and even more were lost to suicide once back in Canada. Constable Dale, a special forces operator with the Canadian Special Operations Regiment with multiple deployments to Central America, experienced his own personal losses.

The two veterans met for the first time while signing their contracts to be Toronto Police officers. Constable Burns had been released from the military several years before Constable Dale and helped mentor him in overcoming the social stigmas associated with asking for help. Early in their career, the two began to identify military veterans on the streets of Toronto who were in crisis, often suffering from suicidal ideations and homelessness. The two treated this as a public safety emergency that needed to be addressed immediately and began to develop their program mantra, “Nobody Fights Alone.”

Through the lens of their lived experiences, the two identified a gap in service delivery and recognized the need for a change. At the time, the Toronto Police Service lacked a program that equipped officers with an understanding of military veterans, aided in de-escalation, and provided a seamless pathway for police officers to refer a veteran in crisis directly to national support services. Constables Burns and Dale both used these supports, which helped change their lives, and they knew the same could be done for others. The two approached their platoon leadership with the idea of helping military veterans. Over the next few months, they worked on the program between 911 radio calls and on their off time, gaining valuable insight from different leaders within the Toronto Police Service. Eventually, the two pitched a more refined plan to their chief of police, who further empowered them to develop the program full-time, underscoring the importance of valuing diverse perspectives within policing.

Community Policing

Constables Dale and Burns knew they couldn’t implement a program like this on their own; they needed the full involvement of the community. They established strong working partnerships with the upper leadership of VAC, RCL, and OSISS.. Constables Dale and Burns continued to gather key stakeholders, advocates, and experts within the veteran community with the combined goal of decreasing veteran suicide and homelessness. Over the years, the team grew to include military veterans and police officers from across Canada, police agencies, academics, health care professionals, entertainers, advertisers, social media influencers, and many others who were eager to help. “This program embodies the proper foundations of community policing in Canada,” stated the Toronto Police Service’s Community Police and Engagement Unit Commander Anthony Paoletta.1

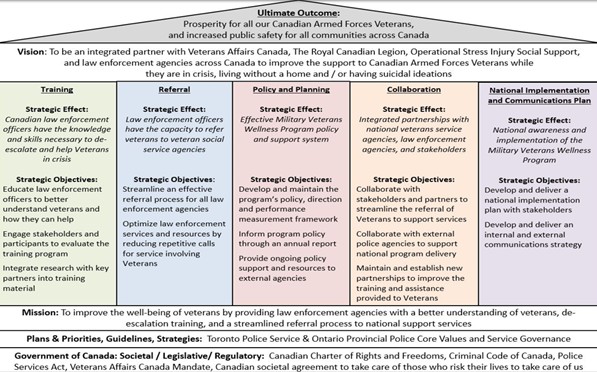

One of the most prominent partnerships for the program early on was the Canadian Department of National Defense, which assisted in developing the structural framework, logic models, and performance measurements. This helped shape the program’s creation by focusing on the five key functional areas: Training, Referral, Policy, Collaboration, Communications, and National Implementation. With a community-based team of experts and a scientific framework to guide the work, the team began to meet regularly to build the program.

Training Program

A significant component of the program is the training package designed for police officers. The program is designed to be delivered online, as it was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which offers easy accessibility for all Canadian police officers. The self-guided, one-hour training program is hosted on the Canadian Police Knowledge Network. The training covers the basics of life in the military, challenges transitioning to civilian life, mental and physical health challenges, how a veteran ends up in crisis de-escalation and negotiation strategies, and veteran social services—as well as how a police officer can help a veteran and refer them to support. More than 145 law enforcement agencies in Canada have accessed the training, and more than 22,000 people have registered to start the online course, accounting for approximately 30 percent of all police officers in Canada. One of the things that made the training successful was that officers genuinely enjoyed it. The program effectively translates knowledge from academics and medical professionals to frontline patrol officers, focusing on only what the course participants need to know for de-escalation. It follows many adult learning principles and offers convenience because much of the training done by frontline officers is during the quiet hours when the emergency call volume is low. Some of the more prominent partners voluntarily helped make the training entertaining:

- Retired Navy SEAL Jocko Willink offered his insight as a leadership expert and retired Navy SEAL.

- Acclaimed author and filmmaker Sebastion Junger highlighted the psychological impact of war.

- The David Lynch Foundation provided video resources to support mental health learning.

- The band Five Finger Death Punch compiled a powerful video on resilience and military life.

Policing is the closest civilian population to military veterans. With this training, many police officers have learned something about themselves and received help for their own personal challenges because they, too, have military service or have similar experiences. One of the program managers, Acting Staff Sergeant Brian Smith, described the program as a mental health training program for police officers in disguise.2

De-Escalation

A major component of the training program is the de-escalation component. Frontline police officers, tactical teams, and negotiators require additional training to ensure a crisis situation involving a veteran has the highest potential to end peacefully with zero harm and zero death. Police officers must understand that the military’s primary job is war, and soldiers are fully immersed in the culture, lifestyle, and calling. Soldiers are trained to detect threats, over-train through repetition, cope with unique stressors, and believe complacency results in death. The Global War on Terrorism has placed a heavy focus on urban and close-quarter battle tactics, using suppressive fire and focusing on locating and destroying the enemy through superior fire and movement. According to Crisis Negotiator Instructor Sharon Havill, with the Solicitor General of the Ontario Public Service, this understanding plays a vital role in training crisis negotiators to understand and address the specific needs of veterans.32

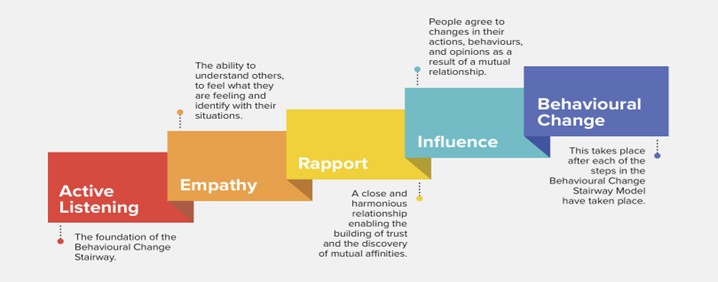

The training teaches the Behavioural Influence Stairway, a commonly accepted de-escalation model, focused on active listening, providing empathy, building rapport, creating influence, and resulting in positive behavioral change.

The best way to provide empathy for a military veteran is to have the same shared lived experiences. However, many officers do not, so they must have the cultural competency training to put themselves in the veteran’s shoes. “Connecting with compassion allows the veteran to feel a sense of safety, recognition, and validation of their struggle, which is the first step on the road to recovery,” stated Toronto Police Officer Constable Scott Bacon.4] The overall program is not only highly effective but also consists of simple techniques and tools to de-escalate crisis situations. As explained by Major James Borer, an international training officer, with the Canadian Armed Forces, the approach also mitigates new potential traumas for both the veterans and frontline officers.5The MVWP recognizes that police cannot provide long-term help, social services can.

Referral to National Supports

Another major component of the MVWP is the referral system. Police officers are perfectly positioned to interact with military veterans in crisis and be the conduit for them to receive help so that another emergency call in the future is avoided. Together with VAC, RCL, and OSISS, the team worked on a procedure that allows any Canadian police officer to refer a veteran roadside from their police car. The referral form navigates individual consent through Person in Crisis legislation, and the preprogrammed button sends it directly to the police-only email inbox for all three agencies. Within 72 hours, the agencies contact the veteran and offer a case manager, advocate, and peer support. This referral process is successful because it is simple and takes a minimum amount of time for an officer to complete, considering they are responsible for several emergency calls waiting in the queue. This referral system can be accomplished only with strong community partnerships that collaborate to achieve the same goals.

One of the first referrals of the program in Toronto included a veteran who was suicidal and living in his car. The individual didn’t feel he was entitled to benefits because he didn’t deploy to Afghanistan and felt that other people were worse off than he was. Officers apprehended the male under the Mental Health Act and took him to the hospital. Through regular conversation, they identified that he was a military veteran and began encouraging him to accept help from national support services. At the hospital, the officers contacted VAC, RCL, and OSISS, who confirmed his military service, placed him in a hotel, and arranged immediate mental and physical health support. The medical assistance continued regularly, and two weeks later, he was placed in temporary housing accommodations. By the end of the month, the veteran had received a permanent place to live, regular medical treatment, and peer support, and he had received his old job back. Not only was the veteran thankful, but the police officers involved in the situation were also proud of their accomplishments and felt they truly made a difference. To date, Canadian police officers have successfully supported more than 250 veterans with this referral process, enabling them to lead fulfilling lives post-service. These success stories serve as a testament to the program’s effectiveness and the transformative power of dedicated support and increased training.

National Expansion

During the creation of this program, Constable Dale and Burns both continued to lose friends from the military to suicide. The two did not want to prevent suicide and homelessness only in Toronto but across Canada. Canadian policing operates in a tiered and decentralized model, so national expansion requires an assertive advertising campaign to promote the program to police chiefs across the country. To promote implementation, the team presented the program at various conferences; launched an aggressive social media campaign; received several endorsements, notably from the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police; and offered the program to multiple police associations and command teams. Any interested police service was provided with an implementation package that outlines the performance frameworks, curriculum, source material, and communications strategies.

Once a police service approves the program, they are provided with a preprogrammed referral form for their internal systems and free training access. The program is currently implemented or in the process of being implemented in more than 85 police services across Canada, which includes approximately 79 percent of all Canadian police officers. The director of the Nicolete Police College in Quebec, Canada, is conducting a final assessment of the course before implementing it across the province, which will bring the total to 93 percent of all Canadian police officers being included in this program.

The MVWP has proven to be a program not only for police officers in Canada but also for other public service organizations, as all can do their part to improve the lives of veterans. There is a growing need for the cultural competency, de-escalation strategies, and access to veteran social services the MVWP provides. The response model in Toronto often involves Toronto fire, paramedics, and police arriving at major emergencies together. “Educating our staff, some of whom are veterans themselves, will go a long way in ensuring we provide the proper ‘first contact care’ with veterans in crisis,” explained Toronto Fire Services Commander Rob Pennington.6

“Beyond the emergency situation, it is vital that Canadian health care providers develop an understanding of military culture, the challenges during a veteran’s transition to civilian life, and their possible health care needs to provide quality care,” stated Dr. Janet Ellis, a medical psychiatrist at Sunnybrook Health Services Centre and a professor of veteran mental health with the Temerity Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto.7 More effective medical care for veterans who have complex medical conditions will result in a better standard of living for those who have served their nation.

Unfortunately, some veterans become incarcerated, partially due to the struggles they have experienced through service. The MVWP is currently being implemented into the Ontario corrections system to prevent recidivism after release. It is essential to connect military veterans with all available support so they have the best opportunity to lead a successful life and not re-offend. The MVWP is a community policing initiative focused on improving the lives of veterans from every possible avenue and public sector. Together, these partners can make a real and lasting change.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canadas federal police service, when implementing the program, recognized that all federal police officer veterans need to receive the same support as military veterans. They were able to take the MVWP and adapt it to support all federal police veterans and military veterans, ensuring police have the ability to support those who serve.

Recognizing Success

In 2024, after five years of continuous development, implementation, and growth, the MVWP hosted its first awards gala to celebrate its achievements. More than 600 leaders from policing, government, politics, and community organizations attended. Several customized awards were presented to more than 150 individuals who helped build the program over the last five years. Those who went above and beyond received a one-of-a-kind certificate cosigned by the minister of VAC and the minister of Public Safety, highlighting the program’s importance as a cross-ministerial initiative. The MVWP is proudly nonpartisan and has been endorsed by leadership across political lines, including then-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and leader of the Official Opposition Pierre Poilievre. This recognition underscores the program’s ability to unify diverse stakeholders under a shared mission: supporting those who served.

A Global Solution to a Global Problem

The need for programs like the MVWP is not unique to Canada. Around the world, many countries experience challenges with their armed forces personnel transitioning back into civilian life post-service. These veterans continue to carry their traumatic experiences and feel the effects of war. Constables Dale and Burns both worked, deployed, and relied upon allied nations for support overseas when they were in the military, and they believe that it’s important for that same mutual support to continue back at home. The United States, Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain, and many other nations experience challenging social issues around veterans’ mental health, incarceration, suicide, and homelessness. Australian Federal Police Superintendent Matthew Ciantar recognized the need for a program like this and helped develop the program for Australia. This development was very timely, considering the 2024 Royal Commission on Defense and Veteran Suicide stated that the Australian police have suicide-related contact with a military veteran every four hours. In Ukraine, where the entire population is affected by war, the MVWP is being adapted as part of the country’s post-war recovery strategy. These challenges highlight the global imperative for the police to play a role in veteran support. The MVWP is proof that police services can be the bridge between veterans and the help they need. Constables Dale and Burns are deploying to Ukraine in early 2025 as part of the Canadian International Policing and Peacekeeping Operations to implement the program further and do their part to contribute to international stabilization. With the assistance of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the MVWP program was presented at the INTERPOL annual conference at their headquarters in Lyon, France. The presentation received tremendous support, and a partnership is underway to have the entire program harmonized for an international audience and available for all 196 member countries. The two are continually supported by their team of experts while away, showing that strong partnerships and grassroot community policing initiatives can change the world. d

The need for programs like the MVWP is not unique to Canada. Around the world, many countries experience challenges with their armed forces personnel transitioning back into civilian life post-service. These veterans continue to carry their traumatic experiences and feel the effects of war. Constables Dale and Burns both worked, deployed, and relied upon allied nations for support overseas when they were in the military, and they believe that it’s important for that same mutual support to continue back at home. The United States, Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain, and many other nations experience challenging social issues around veterans’ mental health, incarceration, suicide, and homelessness. Australian Federal Police Superintendent Matthew Ciantar recognized the need for a program like this and helped develop the program for Australia. This development was very timely, considering the 2024 Royal Commission on Defense and Veteran Suicide stated that the Australian police have suicide-related contact with a military veteran every four hours. In Ukraine, where the entire population is affected by war, the MVWP is being adapted as part of the country’s post-war recovery strategy. These challenges highlight the global imperative for the police to play a role in veteran support. The MVWP is proof that police services can be the bridge between veterans and the help they need. Constables Dale and Burns are deploying to Ukraine in early 2025 as part of the Canadian International Policing and Peacekeeping Operations to implement the program further and do their part to contribute to international stabilization. With the assistance of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the MVWP program was presented at the INTERPOL annual conference at their headquarters in Lyon, France. The presentation received tremendous support, and a partnership is underway to have the entire program harmonized for an international audience and available for all 196 member countries. The two are continually supported by their team of experts while away, showing that strong partnerships and grassroot community policing initiatives can change the world. d

Notes:

1Anthony Paoletta (Superintendent, Toronto Police Service, Community Police and Engagement Unit Commander), personal communication, December 2024.

2Brian Smith (Acting Staff Sergeant, Toronto Police Service), personal communication, December 2024.

3Sharon Havill (Crisis Negotiator Instructor, Office of the Solicitor General, Ontario Public Service), personal communication, January 6, 2025.

4Scott Bacon. (Constable, Toronto Police Service), personal communication, November 10, 2024.

5James Borer (Major, Canadian Armed Forces), personal communication, December 2024.

6Rob Pennington (Division Commander, Toronto Fire Services), personal communication, January 2, 2025.

7Janet Ellis (medical psychiatrist, Sunnybrook Health Services Centre), personal communication, December 2024.

Please cite as

Myron Demkiw, and Aaron Dale, “Nobody Fights Alone: A Global Standard for Supporting Military Veterans,” Police Chief Online, August 13, 2025.