“Reducing violence against women and girls isn’t just about who we arrest. It’s about what we tolerate, what we prioritize, and what we dare to reimagine.”

Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) is among the most persistent, devastating, and complex forms of harm in society. It crosses every demographic boundary—class, race, geography—and manifests in homes, workplaces, streets, and increasingly in digital spaces. The World Health Organization estimates that one in three women globally will experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime.¹ That figure represents millions of fractured lives, countless children raised in the shadow of harm, and the enduring reality that gender-based violence is deeply entrenched in cultural and institutional landscapes.

For policing, this creates a profound challenge. The police’s work is often positioned at the sharp end of this spectrum: responding to crisis, investigating offences, and seeking justice after the fact. However, the policing role must go much further than reactive responses. Policing alone cannot end violence against women and girls, but it has a unique power to convene stakeholders, influence policies and practices, lead whole-system responses, and catalyze transformational change.

Northern Ireland Context: Why It Matters

To understand VAWG in Northern Ireland, one must first acknowledge its specific context. This is a society still shaped by the legacy of conflict, where violence has been normalized for generations and paramilitary control continues to exert influence in certain communities.2 In these environments, women are often subject to a “double bind”: intimate partner abuse is compounded by coercion or intimidation from community structures designed to enforce silence.

Rural isolation adds another layer of complexity. Victims in sparsely populated areas may face significant logistical barriers to disclosure—lack of transport, limited anonymity, and reduced access to specialist services. These barriers are reflected in reporting patterns where, too often, women simply cannot reach police in time or do not believe their voices will be heard.

Institutional mistrust further compounds these challenges. Research conducted by the Northern Ireland Executive Office found that only one-third of women who experienced abuse felt safe reporting to authorities.³ The many complex reasons for this hesitancy include intergenerational skepticism toward policing, fear of reprisal, and a lack of confidence in the justice system.

This is not an abstract policy challenge. It has human consequences. In one of the most sobering findings from recent consultations in Northern Ireland, 98 percent of the women surveyed reported experiencing some form of abuse in their lifetime.4 These figures are a wake-up call: VAWG is a public health crisis, a societal crisis, and a policing crisis, all at the same time.

The Presentation of Violence: Seen and Unseen

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a global epidemic rooted in systemic inequality, power imbalances, unequal gender dynamics, and cultural acceptance of societal norms. In policing, the lens must shift toward understanding VAWG as a pervasive issue. Often misrepresented as isolated acts of physical harm, in reality, the violence operates along a spectrum from overt acts of assault and rape to subtle, insidious behaviors that undermine agency, autonomy, and safety. Coercive control, economic abuse, gaslighting, stalking, and digital harassment are all forms of violence that often remain unreported, unrecognized, and under-policed.

The United Nations’ 2023 Women Count Annual Report highlights that progress in reducing GBV remains slow, and disproportionately impacts marginalized women—such as women with disabilities, migrant women, and those from ethnic minority communities.5 Policing alone cannot dismantle the roots of GBV—but the police’s actions can either reinforce or challenge those roots. From the way reports are recorded and the language used; to the way suspects are investigated, the police’s legitimacy is judged not only by how they respond to violence, but also by how they fail to prevent it.

“The emotional toll on officers who walk alongside victims through their darkest times is heavy, and there are institutional blind spots that can re-traumatize those individuals, that policing aims to protect.”

The murder of Sarah Everard by a serving police officer in 2021 forced UK policing into an unprecedented moment of reckoning. Public trust, particularly among women, was shaken to its core. The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) responded with a commitment to build trust, pursue perpetrators relentlessly, and reform its internal cultures.6 Baroness Elish Angiolini’s review of police misconduct and vetting went further, calling out deep-seated failures in accountability and vetting and the tolerance of misogyny within policing ranks.7

This was closely followed by a 2021 His Majesties Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) inspection that found that VAWG was a “national emergency,” calling for a whole-system approach to prevention, protection, and improved partnerships.8 These reviews and inspections serve as reminders that consent, power, and abuse are not just operational challenges—they are ethical imperatives that go to the heart of the legitimacy of the policing profession.

Every policing action can either perpetuate or prevent harm. Trauma-informed practice, rigorous supervision, and cultural change within police institutions should all be non-negotiable. Victims frequently question the validity of their experiences because the harm is psychological, persistent, and cumulative rather than dramatic or immediate. Police practitioners must be attuned to this nuance—asking not only “What happened?” but “How does it feel to live with this every day?” Operationalizing this understanding means strengthening training in recognizing non-physical abuse, improving the questions in risk assessments, and building multi-agency safeguarding approaches that acknowledge chronic patterns of harm. A bruise-less victim is not a violence-free victim.

Policing’s Role: Reactive by Nature, Transformative by Choice

The police must lead from the front, but also listen from the ground—because the voices closest to the harm hold the key to transformation and will help to inform a critical debate: Is policing truly positioned to prevent VAWG or is it destined to merely respond? While law enforcement is essential in securing justice, prevention lies in societal transformation. That means investing in education, public campaigns, and collaborative safety planning. It also means reforming the police in areas such as vetting, supervision, and officer welfare. The “policing of VAWG” cannot be reformed without reforming the “policing culture” that women experience inside and outside police organizations.

Much like the crime itself, policing and the wider criminal justice process has at times disproportionately focused on victim credibility instead of taking a perpetrator-centric approach and utilizing an ABC framework: A (Actions), B (Behaviors), C (Connections). Using this framework allows for pattern recognition across offenders, supports proactive intervention, and links repeat offending behaviors. This, coupled with effective cross-system data sharing and working and intelligence-led tasking, remains underdeveloped. Predictive models, enhanced analytical capacity, and the courage to move upstream are all needed to go beyond responding to risk and toward disrupting it.

Gaining valuable insights into offending behavior, through the use of behavioral change models, such as COM-B, which conceptualizes behavior as part of a system of interacting factors. This model allow for an understanding of what Capability and Opportunities offenders have and what Motivates them to Behave in a certain way.9 Understanding and responding to the risk posed and developing interventions that then target behaviors are pivotal to successful interventions, such as persuasion through the development of communication to induce positive or negative feelings to stimulate action; education through targeting the knowledge or understanding of the issue; incentivization or coercion to demonstrate the consequences of behavior (negative and positive); and by modeling aspirational behaviors.10

Global Perspectives, Local Application

For the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), and for all global policing institutions, there are lessons to be learned, as many of the same challenges are faced across the world. It is impossible to ignore that the legitimacy of policing has been historically contested and that some communities—particularly those most vulnerable to gendered harm—remain skeptical about engaging with the justice system.

Cultural reform within policing is not optional; it is foundational and The Police Service of Northern Ireland is targeting the issue through the following actions:

- Launching a Violence Against Women and Girls Action Plan11

- Aligning with national best practice12

- Enhancing vetting procedures to identify risk early

- Instituting mandatory trauma-informed training for frontline officers

- Empowering local VAWG champions who drive change from the ground up

- Embedding lived experience into training and policy development, ensuring victims’ voices are heard not only in casework but in system design

Through this work, the PSNI has responded to the police’s traditional role as reactive to the issue, not disruptive and moving beyond when harm has already occurred. Through lessons learned – if the policing profession is truly serious about change – policing must shift from “incident management” to “harm prevention.” This does not mean abandoning enforcement, but it does mean expanding the police’s role as leaders in prevention, education, and partnership.

“Beyond the badge, the police have a duty to protect with empathy, to act with integrity, and to use their authority not only to enforce the law but to reimagine the society they serve”

This is at the heart of Northern Ireland’s Ending Violence Against Women and Girls (EVAWG) Strategy—a 10-year framework led by the Executive Office.13 It recognizes that gender-based violence is not just a criminal justice issue, it is a systemic human rights issue, requiring cross-government collaboration across health, education, housing, and community sectors.

Through this strategy, policing is a partner and a convenor. Police data are used to identify patterns of harm, and multiagency partners come to the table to design interventions. Survivors are engaged to ensure their experiences drive policy reform. This is whole-society policing in action.

Countries across the world are adopting other innovative responses:

- Sweden has redefined rape law around affirmative consent.14

- Scotland’s “Equally Safe” strategy integrates public health, education, and justice.15

- New Zealand invests heavily in restorative approaches, giving survivors a greater voice in justice processes.16

- The Istanbul Convention sets the international gold standard—prevent violence, protect victims, and prosecute offenders—across all sectors, not just policing.17

These global shifts demonstrate that with political will and public partnership, systems can be redesigned. Northern Ireland will continue to learn and where applicable, adopt these global principles. However, the PSNI must also confront its own blind spots: the absence of robust data for victims and offenders under 16 years old, digital forensics delays, the gaps in support for rural and minority women, the response to the increasing online threat, and the growing manifestation of misogyny in the counterterrorism space.

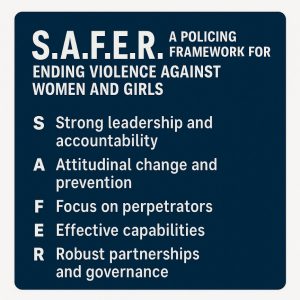

The S.A.F.E.R. Framework: A Strategic Toolkit for Policing VAWG

The author’s experience in this realm led her to develop a framework for delivery that can be scaled and adapted.

The S.A.F.E.R. VAWG model can be used wherever policing seeks to balance enforcement with prevention, and justice with survivor journey to embed VAWG policing responses across strategy, operations, and partnerships:

- S – Support Victims and Strong Leadership: Build trauma-informed, victim-centered engagement. Improve safeguarding through a consistent multiagency response and specialist advocacy.

- A – Awareness, Education, and Prevention: Invest in public campaigns and contribute to school-based programs and officer training to shift cultural norms around misogyny and consent.

- F – Focus on Perpetrators: Move investigations upstream, using tools like the ABC model (to map and disrupt offenders.

- E – Effective Capabilities and Evidence Led: Harness data analytics for precision policing, integrate cross-agency data, and evaluate interventions to drive continuous improvement.

- R – Relationships, Partnerships, and Governance: Build co-designed and owned accountability processes through partnerships with voluntary, community, and statutory agencies with the voice of those with lived experience at the heart of everything the police and their partners do.

The Weight We Carry

The emotional toll on officers who walk alongside victims through their darkest times is heavy, and there are institutional blind spots that can re-traumatize those individuals, that policing aims to protect. Every investigative decision carries a moral imprint and officer support and well-being must be considered alongside victim safeguarding. It is neither courageous nor sustainable to expect frontline staff to consistently perform in an area with high levels of trauma without robust support.

It is critical to design systems that don’t require survivors to be brave just to be believed or officers to reach their breaking point before leadership intervenes.

VAWG is preventable, not inevitable. Yet it demands institutional bravery: confronting misogyny in the ranks, challenging internal cultures, disrupting perpetrators early, prioritizing online safety, and better aligning policing with justice and health systems.

While policing alone cannot end VAWG, it has a unique power to lead, convene, and influence. Beyond the badge, the police have a duty to protect with empathy, to act with integrity, and to use their authority not only to enforce the law but to reimagine the society they serve through demonstrating transparency and earning trust through every interaction. That is how the police professional can help to shape societies where freedom from violence is not exceptional but expected. d

Notes:

1World Health Organization (WHO), Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates (WHO, 2021).

2McAlister, S., Neill, G., Carr, N., & Dwyer, C. (2021). Gender, violence and cultures of silence: young women and paramilitary violence. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(8), 1148–1163. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1942807

3End Violence Against Women & Girls – Strategic Framework: Consultation Summary Report (North Ireland Executive, 2024).

4End Violence Against Women & Girls.

5UN Women Count Data Hub, 2023 Annual Report: Driving Transformative Change on Gender Data: January–December 2023 (UN Women, 2024).

6National Police Chiefs’ Council, “NPCC Response to the Angiolini Inquiry Part 1 Report,” news release, February 29, 2024.

7Elish Angiolini, The Angiolini Inquiry Report, 2024.

8His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS), Police Response to Violence Against Women and Girls – Final Inspection Report (HMICFRS, 2021).

9Susan Mitchie, Lou Atkins, and Robert West, The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions (London, UK: Silverback Publishing, 2014).

10Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), “Men and Boys in Northern Ireland Challenged to Change Their Attitudes Towards Women and Girls in New Campaign,” news release, January 29, 2025.

11PSNI, Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls Action Plan (PSNI, 2021).

12College of Policing, NPCC, Policing Violence Against Women And Girls – National Framework For Delivery: Year 1 (College of Policing, 2021).

13End Violence Against Women and Girls: Strategic Framework 2024–31 (Northern Ireland Executive, 2024).

14 Swedish Government, Consent-Based Sexual Offences Law, 2018.

15Scottish Government and COSLA, Equally Safe: Scotland’s Strategy for Preventing and Eradication Violence Against Women and Girls (2018).

16New Zealand Ministry of Justice, Restorative Justice Practice Standards, 2022.

17Council of Europe, Action Against Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence: Istanbul Convention.

Please cite as

Zoe McKee, “Reducing Violence for a SAFER Future: Enhanced Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls,” Police Chief Online, November 05, 2025.