Everyday police work involves a range of decisions. One of the primary goals in academy training is to ready officers for this decision-making environment. Often, the policing environment is fast-paced and requires rapid analysis before a course of action is taken. The well-known fast decisions in policing are generally related to use of force. But there are a range of other areas where fast decisions happen in the form of visual scene analysis, tactical positioning, and kinesics interview skills.

Because of the preponderance of fast decisions in policing, a “first principles” approach to look at fast decisions on a neurological level was employed and then applied to the development of officers’ decision-making skills in an academy setting.

Neuroscience Fundamentals of Decision-Making

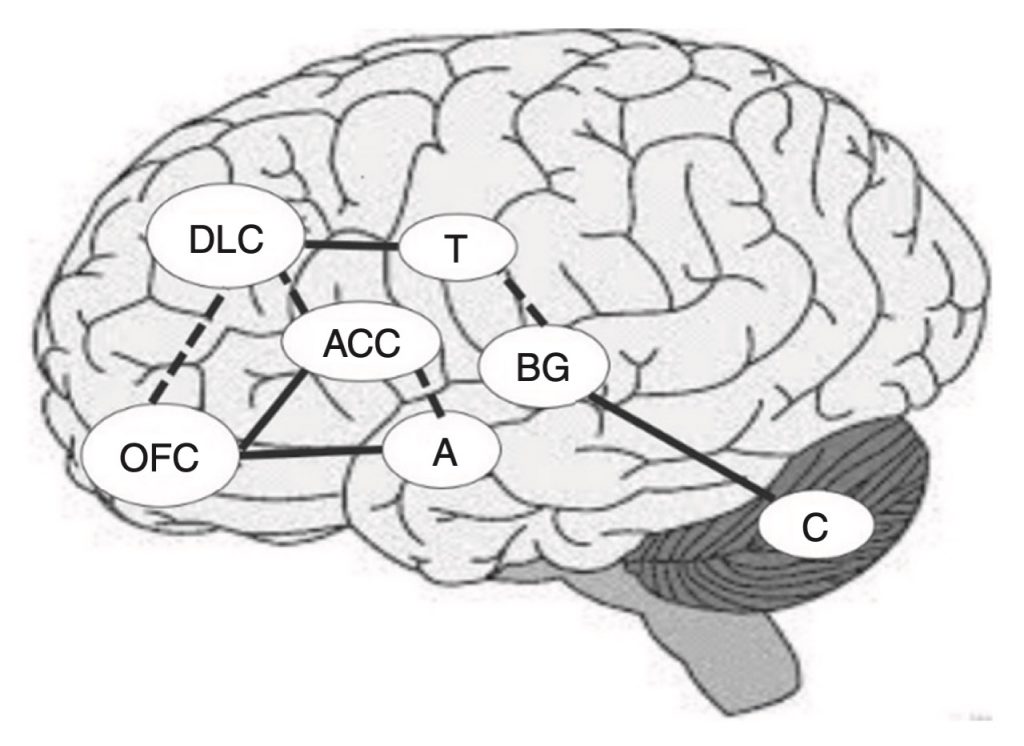

The neuroscience literature is rich with studies and meta-studies that summarize which regions are involved in various aspects of decision-making.1 Cortical regions on the outermost layer of the brain interact with interior structures to provide a blend of executive skills and rapid, emotion-driven decision processes. These structures also interact with the movement areas, both in cortical and interior brain structures, to affect the body’s action in the world.

The below diagram provides a model to understand the neuroanatomical elements of decision-making. Here, the cortical regions of the Dorsolateral Cortex (DLC) and Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) are shown by anatomical connection to interior structures, such as the thalamus (T) and the Basal Ganglia (BG). The DLC and OFC represent areas largely responsible for executive skills in decision-making, while T and BG are interior structures connected to emotion processing. In turn, the BG is connected to the Cerebellum (C), which is a primary driver in movement and balance.

This description of decision-making in the brain is not complete or comprehensive. Other parts of the brain become involved, depending on the nature of the decision. But the primary elements of interacting cortical, sub-cortical (or interior) and movement structures are common to all decisions, even ones where no movement is made (i.e., an inhibition response). These general neural mechanics for all decisions can be illustrated by the decision to hit a baseball, which is described in the next section.

The Neuroscience Mechanics of Decisions in Baseball Hitting: The Stimulus

The task of hitting a baseball provides a useful template to understand decision processes, and ultimately how they apply to policing decisions. For instance, baseball hitters must see the path of the ball coming toward them (using visual cortical areas), decide if they will swing (using DLC and OFC) and coordinate movement or inhibition to swing at or take a pitch (using BG or C). Task simulations can help to measure these processes in action.

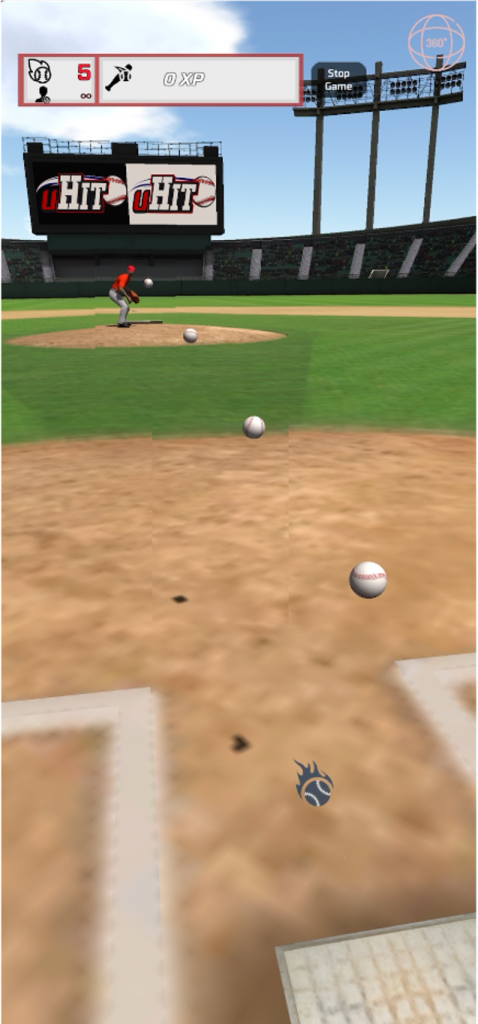

As a result, the first step to parsing the neuroscience of decisions in hitting a baseball—or in any other field, such as policing—is to determine the relevant sensory inputs to the brain. In the simplified world of balls and strikes, only the trajectory of the pitch matters to the task of swinging at strikes and taking balls. In fact, this simplicity of the stimulus makes it ideal as a basis to understand the principles of decision-making. In numerous studies, the trajectories of pitches have been simulated in a game-like environment to mimic a real-life scenario.2 An example of one of these trajectories is shown in this time-lapse image.

After a pitcher winds up, the release of the pitch initiates a ball trajectory from which four snapshots are shown in Figure 2. From that trajectory, a hitter records his decision to swing at such a pitch by tapping on a mobile device screen or clicking a mouse (gray baseball indicates an onscreen tap). If the hitter wishes to take the pitch, or indicate it is a ball out of the strike zone, then he simply refrains from tapping or clicking, just as he would inhibit a swing in the real-life analog.

The ball trajectory in this example is more generally known as “the stimulus” because it is the external sensory input that stimulates the decision under study, which in this example is hitting a baseball. There is a wealth of information available to analyze and hone someone’s decision skills from only their taps/clicks (or inaction) in response to the stimulus. Additionally, the brain activity correlates that occur before and during the stimulus, up to and after the decision reveal the electrical and hemodynamic (i.e., blood flow) activity driving decision performance. It is this underlying neural activity that provides a map in space and time of how a hitter interprets the stimulus as it comes toward him and acts accordingly. Together, the speed and accuracy of physical decisions (taps or clicks) and the correlating brain activity provide an assessment of the hitter’s ability to swing at strikes and take balls in the real world.3

The Neuroscience Mechanics of Decisions in Baseball Hitting: The Response

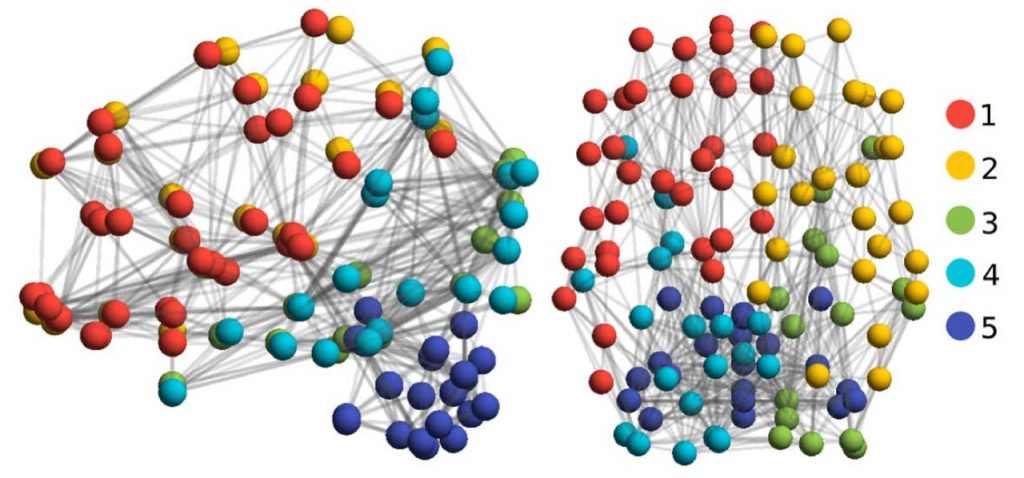

Using this approach, the authors were able to map the regions unique to baseball hitting decisions. Like the decision-making model shown earlier, hemodynamic data revealed the modular organization of hitters’ brains, as shown in Figure 3.4 The five most dominant modules across hitters are color-coded, from red (Module 1) to blue (Module 5).

For instance, Modules 1 and 2 are cortical areas, though they are more specific than the broad areas described earlier as DLC or OFC. Module 5 is nearly exactly overlaid on the region labeled “C” for cerebellum earlier.

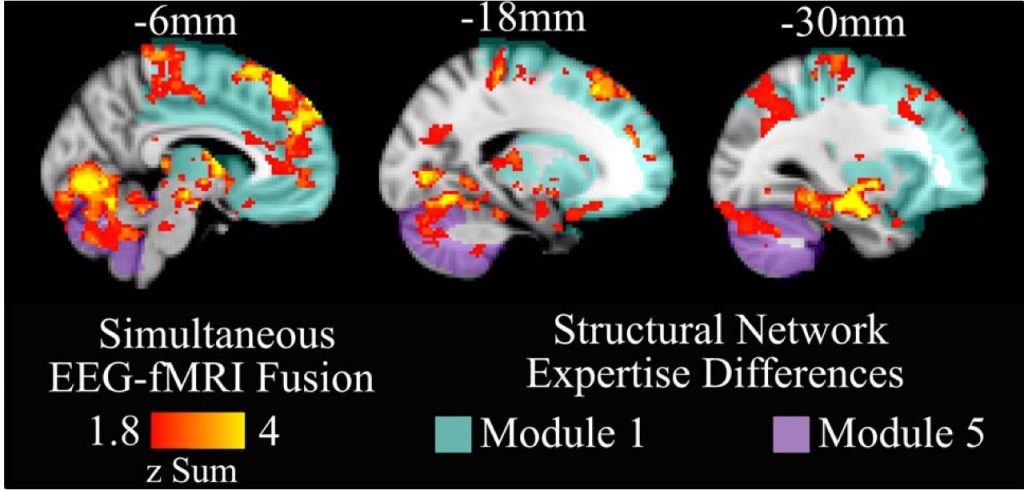

When we combined the electrical brain activity measurement with that of the hemodynamics, we found that there were structural differences in hitters who had developed expertise at this skill. These differences particularly manifested with regard to how well-connected were the five modules. For instance, Figure 4 shows the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) structural brain view at three different cross-sections. In each cross section, the structural differences for more expert hitters are heat-mapped on top of Modules 1 (cortical) and 5 (cerebellum).

While this level of analytic detail is beyond what is needed in police training, these results lead to implications for training, either for baseball hitting or other fast decisions, like those that occur in policing. Such analyses highlight that the goal in expertise development is to enhance the connections between regions of the brain that are driving decisions. These better connections lead to faster and more accurate decisions in those who have developed expertise.

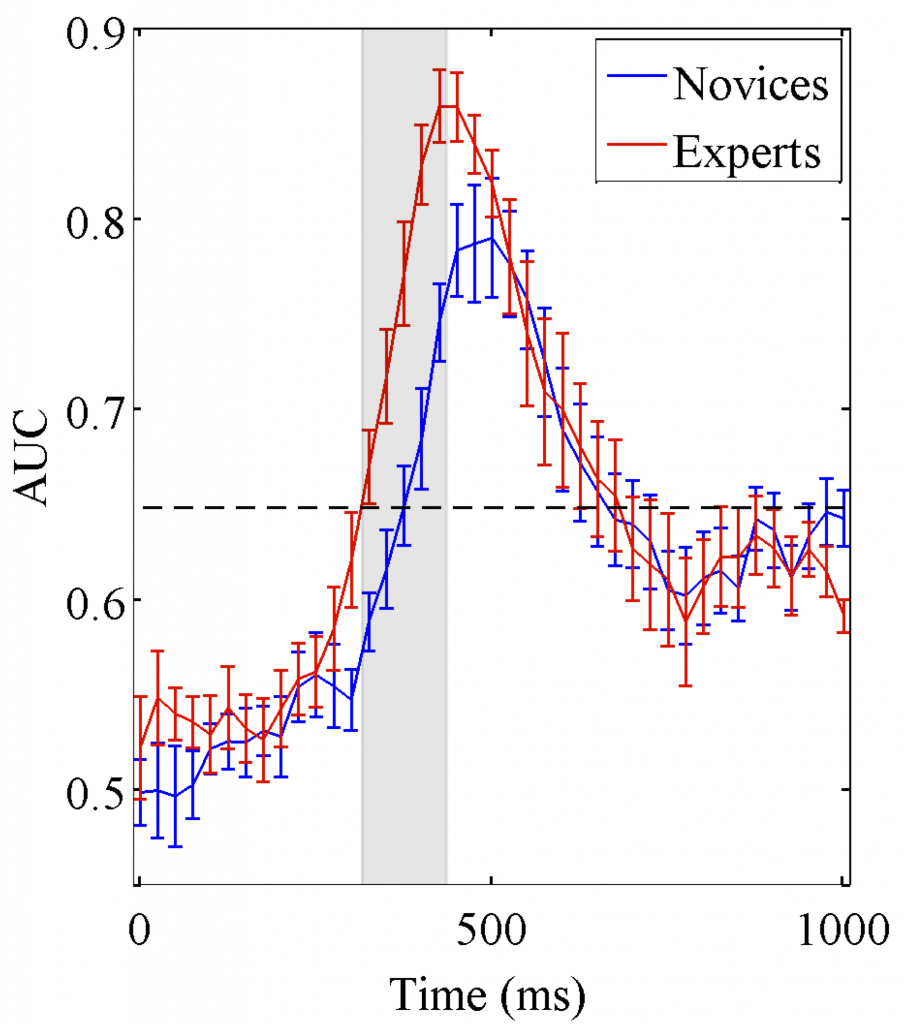

Data on the efficiency of this enhanced connectivity among experts was collected by measuring the electrical activity of the brain response to the stimulus—with the pitch starting at 0 milliseconds (ms) below and coming forward in time over the next ~600 ms. Figure 5 shows how the brain’s response for expert hitters (red line) differs by being faster and more pronounced than that of novice hitters (blue line).5 In other words, the noted structural differences are the material drivers of expert hitters being able to see and decide on pitches faster and more accurately than their novice counterparts.

With this detailed look at fast decisions, measurement techniques that can more easily fit in policing can be selected. In particular, not all of these analytic techniques fit the operational constraints of either academy or in-service training. The next section describes how the stimulus-response paradigm used to analyze baseball hitters translates to developing and evaluating police decision-making skills and training.

Measuring Decisions in Policing: The Stimulus

In policing, the stimulus is different when measuring the brain of an officer while engaged in tasks similar to the ones engaged in real law enforcement encounters. The stimulus is also more complex than a pitch trajectory because of the range of encounters regularly seen in policing. Today, a broad range of choices are available to simulate tasks like those police encounter. From live role-play to virtual reenactments or video of encounters, there are a wealth of ways to portray the stimuli police officers are exposed to. One category of stimuli, though, stands out for its similarity to what officers encounter in real-life: body-worn camera (BWC) footage.6 For that reason, BWC footage was used as the underlying stimulus to measure an officer’s decision skills.

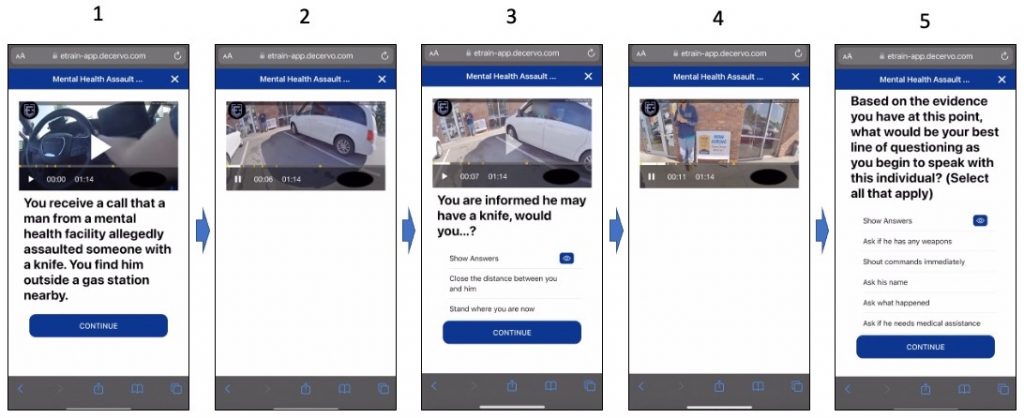

The BWC footage alone though is not sufficient to measure policing decisions. On top of this video, specific questions were posed and certain time-pressured tasks were required of officers to gauge their skills in a given situation. Like in the baseball hitting paradigm, the same format of time-pressured tasks led to a wealth of information. These tasks were grouped to fit the range of encounters seen in policing. The tasks can be questions posed with single choice answers (such as true/false) or multi-choice answers (choose all answers that apply). Examples from a scenario created with underlying BWC footage are shown in the sequence of screenshots in Figure 6.

Proceeding from left to right, we begin with (1) background info before arriving on scene, (2) footage from approaching the man who is subject of the call, (3) the first question posed to the officer (single choice), (4) more footage of interacting with this man, and (5) the second question posed to the officer (multi-choice).

Although not shown in this example, other questions can be used to probe officers’ decisions, such as how likely they believe something is true (e.g., on a 1-5 scale) or whether they can see something of importance (e.g., sign of a concealed weapon), indicating visual search skills by a tap on the screen. Furthermore, every question is tagged by topic. For instance, the multi-choice question in Figure 6 is tagged as a question in tactical, mental health crises, and de-escalation decisions.

In this way, a series of scenarios based on BWC footage provide a way to gauge decision accuracy and time to respond to the stimulus. To cover a broad range of policing decisions, the scenarios covered the following categories:

- Vehicle stops

- Mental health crises

- Tactical

- De-escalation

- Domestic violence

- Use of force

- Suicide by cop

- Kinesics training

- Constitutional policing

- DUI

Furthermore, the questions can cover many of the above categories at once, much like decisions do in real-life encounters. For every question, the time it takes for an officer to select answers was also measured. In this way, data on accuracy and decision time for each of the categories and across all policing decisions were collected.

Measuring Decisions in Policing: The Response

Results from evaluating the policing decisions of recruits in an academy illustrate the efficacy of this approach. In a two-month segment of the academy, the recruits who completed training made 287 decisions over 57 scenarios. Their overall decision accuracy was 78 percent and decision time was an average of 1.64 secs. The breakdown of decision accuracy and time by each category is shown in Figure 7 (in same order from left to right).

Leading with the highest accuracies, the academy class excelled in vehicle stops (83 percent) and mental health crises (79 percent). Conversely, suicide by cop (74 percent), kinesics training (74 percent), constitutional policing (74 percent) and DUI (70 percent) were the most difficult topics for the class.

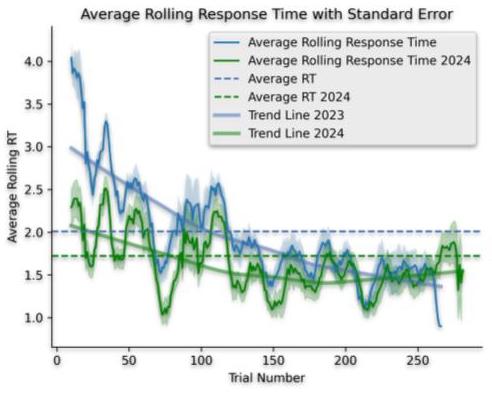

In this breakdown, decision time by topic over the whole academy can be seen, but that does not capture the overall changes found in decision time during the class. Rather, Figure 8 shows the change in decision time (calculated as a rolling average) across the 287 decisions made during the class.

The trend line through the rolling average shows how decision time decreased (sped up) and ultimately leveled off toward the end of class. When decision accuracy is maintained, a steady decrease in decision time indicates both faster processing of the stimuli officers witness and more efficient translation of that information to action. Such improvements in processing time and translation to action are critical for officer safety, especially for recruits who will further develop their skills in real life after their time at the academy.

Using Decision Measurements in the Academy

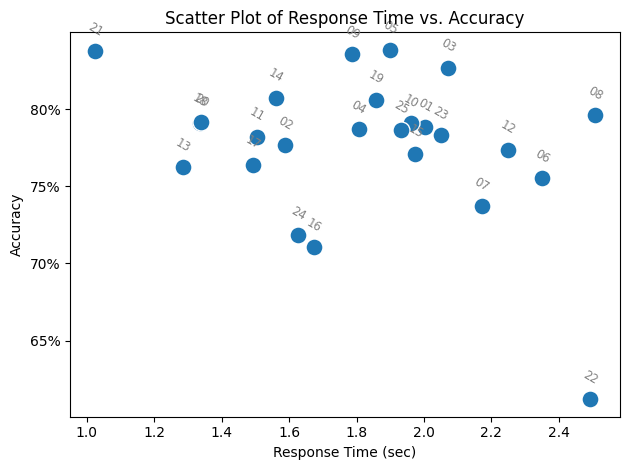

Beyond the individual measurements of accuracy and speed, the combination of these metrics provides useful insights about policing decisions. Just as the speed of expert baseball hitters’ brain responses differentiated them from novices, the combination of accuracy and speed in policing decisions can be used to identify recruits who are best integrating the curriculum into their decisions. In the academy setting, an analysis of the speed-accuracy tradeoff via a scatterplot of each officer’s decision accuracy and speed during the class can be conducted. Figure 9 presents that plot.

The points generally cluster toward the top and middle of this plot. For instance, most officers’ accuracies are above 75 percent and have decision times between 1.4 and 2.2 seconds. Slower decision times with good accuracies (such as #08 or #06) are less concerning than slow decision times and a poor accuracy (such as #22). In the latter case, greater processing time is not aiding the retrieval of the right decision during a scenario. But in the former cases (#08 and #06), the officers are generally finding the right decision, though their lack of experience is slowing down retrieval.

Importantly for recruitment and retention, the plot of decision speed vs. accuracy has proven a useful part in identifying recruits who will make it through academy. In this class, as seen in others, the outliers on this plot are consistently the recruits that do not complete academy. From the above plot, #22 was identified. But the other two outliers in low accuracy (#24 and #16) together with #22 did not complete academy training.

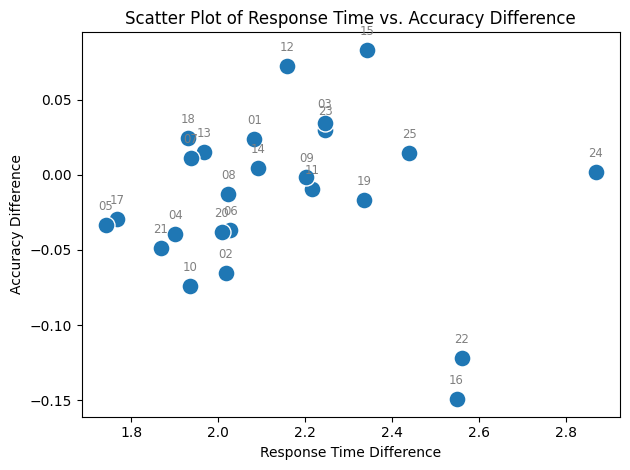

Dropout tendency is even clearer when examining decision time and accuracy by question type. In particular, the evaluation of decision accuracy/time difference by whether the question posed requires a single choice or multiple choices provides an avenue to understand a recruit’s decision confidence. For this academy class, the scatter plot technique was used again to visually show the clustering of the recruits by this difference as seen in Figure 10.

Most of the recruits in this plot cluster to the left upper corner, below 2.5 seconds time difference. Again, three outliers appear, now more clearly than the speed-accuracy plot earlier. Specifically, #24 is a major outlier in time difference between single and multi-choice decisions. #22 and #16 are outliers by time difference and both are significant outliers by accuracy difference, with their multi-choice decisions being 10-15 percent less accurate than their single choices. In the case of #24, the extended time difference indicates a decision hesitancy when multiple choices need to be made. In the case of #22 and #16, the appearance of multiple possible decisions is impacting their ability to sift through irrelevant options and make the right decision.

Together, the speed-accuracy and the single vs. multi-choice plots provide a quantitative way to evaluate the policing decisions of recruits in academy. For purposes of recruitment and retention, such analyses can either highlight when remedial training might be necessary, or when an agency has a recruit in training who is not going to be able to meet the demands of deciding under the time and pressure constraints of policing.

Lessons Learned

A foundation in the neuroscience of decision-making can be used as an analog to capture the underlying network interactions occurring in the brain and to highlight the speed and accuracy of an officer’s decision. From a basic model of the neuroanatomy of decision-making, to the specifics of what brain regions interact in sequence, the neuroanatomical drivers of decision accuracy and speed in a time-pressured task (such as baseball hitting) can be plotted. BWC footage-based curriculum was used to gauge policing decisions, also made under time pressure. Measuring decision speed and accuracy of recruits learning policing decisions in an academy setting was applied.

This study found these metrics could be used to highlight recruits who struggled to integrate academy curriculum into their policing decisions. First, the tradeoff in decision speed and accuracy provided an indicator of the likelihood a recruit would finish academy training. Recruits that were outliers in terms of the tradeoff of decision speed and accuracy were more likely to drop out of academy before completion. Second, accuracy/time differences in single choice vs. multi-choice questions provided an additional way to highlight recruits’ abilities to make decisions among a range of options. Recruits in the lowest quartile for these accuracy differences were most likely to drop out of academy, or otherwise not complete training. Outliers in both plots were the same and ultimately indicated officers who did not complete academy training.

Recommendations

Interest in incorporating neuroscientific findings into police training and evaluation is increasing. But the specific path from theory to practice has been difficult to find, balancing scientific rigor with the operational constraints faced by officers. Here, the study began from an underlying theory of decision-making being manifest by the interaction of specific brain regions. In expert decision-makers, how these regions interact with optimal efficiency to deliver performance gains in both decision time and accuracy was seen. The use of stimuli that contain relevant cues upon which decisions are based is a fundamental component to evaluating this expertise. For baseball hitters, trajectories of pitches simulated in a batter’s box was used. For officers, a curriculum was integrated with BWC footage.

In policing, using stimuli that offer an appropriate level of realism (such as BWC footage) and a way to measure decision time and accuracy to these stimuli is recommended. In academy instruction, a mechanism for separating decision time and accuracy by topic, such as vehicle stops or constitutional policing, can be useful. For individual officers, an evaluation of decision time and accuracy by topic provides metrics of relative strengths and weaknesses in those officers’ decision-making. For the academy as an institution, these metrics provide vital feedback on the efficacy of its instruction.

Finally, using decision time and accuracy metrics in the recruitment and retention of officers is recommended. Here, we have highlighted the use of these metrics within and across different question types to evaluate whether certain recruits have sufficiently incorporated academy curriculum into their decisions.

In the future, a community engagement aspect to this type of decision-making evaluation may build community trust, too. Agencies can use curriculum based on BWC footage to measure policing decisions in this way among cadets, police explorers, or community members (community police academies). In that way, community members and those considering a career in policing can get advanced awareness of what types of decisions officers regularly face, and potentially gain advanced insight into their strengths and weaknesses at making them. d

Notes:

1Yunier Broche-Perez, Luis Felipe Herrera Jiménez, and Erislandy Omar-Martínez, “Neural Substrates of Decision-Making,” Neurologia 31, no. 5 (2016): 319–325; Hans Liljenström, “Consciousness, Decision Making, and Volition: Freedom Beyond Chance and Necessity,” Theory in Biosciences 141 (2022):125–140.

2Jason Sherwin, Jordan Muraskin, and Paul Sajda, “You Can’t Think and Hit at the Same Time: Neural Correlates of Baseball Pitch Classification,” Frontiers in Neuroscience 19, no.6 (2012): 177; Jordan Muraskin, Jason Sherwin, and Paul Sajda, “Knowing When Not to Swing: EEG Evidence That Enhanced Perception-Action Coupling Underlies Baseball Batter Expertise,” NeuroImage 123 (December 2015): 1–10; Jordan Muraskin et al., “Fusing Multiple Neuroimaging Modalities to Assess Group Differences in Perception-Action Coupling,” Proceedings of the IEEE 105, no. 1 (2016): 83–100.

3Jordan Muraskin and Jason Sherwin, “Multiyear Improvement in Batting Skills Following Targeted Perceptual Cognitive Training in Softball,” bioRxiv, September 2024; Jason Sherwin, “Division I Hitting Results in 2024,” last modified August 12 2024; Jason Sherwin, “Part 2 of MLB Org Assessment Case Study,” last modified March 30 2024.

4Muraskin et al., “Fusing Multiple Neuroimaging Modalities to Assess Group Differences in Perception-Action Coupling.”

5Muraskin, Sherwin, and Sajda, “Knowing When Not to Swing.”

6Rudolph B. Hall Jr., “Specialized Police Units: NYPD Anti-Crime and the Effect of Body-Worn Cameras” (EdD diss. St. John Fisher University, 2020).

Please cite as

Jason Sherwin and Mark Rusin, “Translating Neuroscience for Academy Training Success,” Police Chief Online, December 10, 2025.