The starting point in the development of this interview protocol began years ago, when it was realized, as in so many police services, of the need to improve police interviews of victims, especially victims of sexual assault. Training courses on the common impacts of trauma on victims’ thinking, behavior, and memory formation by Dr. Jim Hopper1 2 (independent consultant and teaching associate at Harvard Medical School), and the associated trauma-informed approach to interviewing provided by the IACP and EVAWI3 4 were revealing. The authors (a lieutenant and a forensic psychologist in the Quebec Provincial Police) worked together to combine science with practice, recognizing during the process that the approach needed a structured interview to properly guide investigators applying trauma-sensitive methods.

The science on trauma-informed policing is often very interesting and guides good practice, but it’s not necessarily easy for an officer to apply in the field. A better understanding of the victim’s needs in the context of the police interview; the incorporation of knowledge on common effects of severe stress on thinking, behavior, and memory; and reframing questions as recommended in the trauma-informed approach were essential. Despite the good will of investigators, without a structure as a guideline, there was a risk that in the heat of conducting an interview, investigators would, more or less consciously, revert to “old school” methods. In other words, they would put the focus back on the “Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How.” Basically, many investigators could be overly focused on the primary function of their work—obtaining information to carry out their investigation—and appear as less empathetic to the victim.

The project for a structured trauma-informed police victim interview quickly took shape. The authors turned to two scientists, and several years of collaboration began with Dr. Jim Hopper (clinical psychology) and Dr. Ron Fisher (cognitive psychology, Florida International University), both experts in the memory process and the latter the developer of the traditional Cognitive Interview, the most researched and validated eyewitness interviewing approach. Beginning in 2022, the team met regularly on a virtual platform and worked on adapting the traditional Cognitive Interview5 6 7 to victims of physical or sexual assault, which included conducting 70+ interviews with sexual assault victims. The team brainstormed regularly and adjusted the interview structure along the way. The traditional Cognitive Interview was used as a starting point, and the investigator’s experience of this interview format allowed for the progressive development of the trauma-adapted version, working directly with victims. As a result, the four specialists arrived at the Cognitive Interview Adapted to Trauma (CI-AT), which uses a simple interview structure/method that aligns with the best ways to elicit the most complete and accurate memories of the victim’s experiences, thinking, and behavior during the assault.

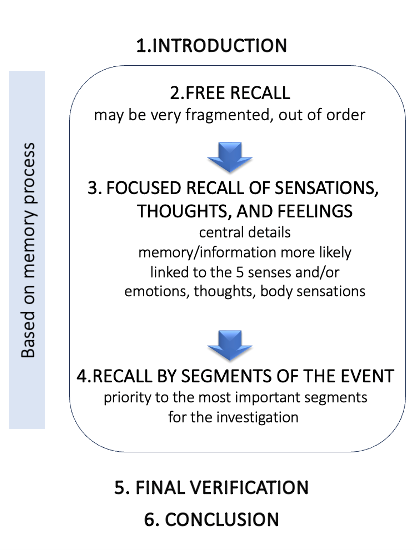

The CI-AT’s Six Phases

A basic principle underpinning the CI-AT is that stress affects memory, from encoding and storage to recall8 . The six-phase interview structure seeks to mitigate the stress for the victim while still obtaining the key information required for an investigation.

Phase 1: The Introduction

Phase 1 of the CI-AT, the introduction, is the victim’s preparation for the police interview, which is an out-of-the-ordinary experience for most people. No one ever thinks they’ll find themselves in a police station recounting an assault. With this in mind, investigators try to reduce stress for the victim as much as possible, thus optimizing memory recall and victims’ comfort. Elements included in this phase can be grouped into three sections. First, the investigator introduces themself and explains that the meeting is recorded on video, which completely and accurately conveys what the investigator and the victim say in the interview, something a written statement by them or reported by the investigator cannot do.

Second, the interviewer tries to reduce performance stress that many victims experience because external or self-induced performance pressure to remember could have the opposite of the intended effect. Victims are reassured that they don’t have to be “perfect.” If information is not in their memory, it’s just not there. The recall capacity will vary for each victim.

Also, if they are uncertain about a particular detail or piece of information, victims are invited to share it while communicating that they’re uncertain about it to some extent. Sometimes even uncertain information can turn out to be important in an investigation. Finally, victims are invited to speak up if any questions make them feel uncomfortable or feel judged (mistakenly or not). The interviewer can then clarify a question, correct a faux pas, or help the victim feel safer again before proceeding.

The third section of the CI-AT’s introduction is to explain what to expect in the meeting, briefly explaining the type of interview, including that it won’t be question-and-answer like in the movies. Investigators will listen more than question. They will go back over certain points. They will ask victims to describe, in their own words, certain things they’ve already reported in order to clarify or to reduce and hopefully eliminate any misinterpretations during the whole judicial process.

In the case of adolescents or adults, telling them that they are in this interview to “tell the truth” would be counterproductive by suggesting from the outset a suspicion that they might be lying.

Investigators end this phase by asking victims if they still want to do the interview. This conveys that they are in control and can refuse or ask to stop for a break or even put an end to the interview at any time. It’s up to them. Victims’ levels of comfort or stress are linked to their senses of autonomy, competence, and security in the interview. At this point, their consent to continue often resembles a form of firm commitment, with some even stating that they are ready to face the challenge that such an interview could present for them.

These elements of the introduction are essential. Rapport between investigator and victim is created in this phase, based on addressing victims’ needs specific to the context of a police interview. In the past, a light and informal type of conversation was used trying to create a rapport. But many victims were puzzled by this and questioned its relevance. Furthermore, personal information unnecessary to the investigation could be revealed and have to be redacted later. Too much personal information could represent a risk for victims, if it wasn’t already known to the perpetrator, e.g., place of work, activities, or the like.

Phases 2–4

The introduction (Phase 1) is followed by three phases designed to elicit and assess recalled and reported memories:

- Phase 2: An entirely free recall

- Phase 3: Focused recall of sensations (including the five senses prioritizing one at a time) and internal experiences of emotions, thoughts, or bodily feelings

- Phase 4: The “segments” phase of the interview is about eliciting more information about two or three particular segments of the event

Trauma-informed victim interview training allows investigators to have more realistic expectations of a victim’s recall ability. Phases 2, 3, and 4 of the CI-AT interview structure are different ways of guiding memory recall. This progressive search for information is based on how encoding and storage in memory tend to work during an assault or any other extremely stressful experience, and on scientifically validated methods for eliciting the most complete and accurate information, including by avoiding any leading or suggestive questions.

Phase 2: Free Recall

No one recalls everything about any experience, but for highly stressful events, memories are generally less complete and more fragmented with only the most “central details” (based on attention and significance at the time) getting encoded and stored. This is even more the case if there was intoxication (voluntary or involuntary) during the assault. However, just because alcohol9 or other drugs reduce the amount of information recalled, that does not mean they reduce the accuracy of any information that can be recalled.

Free recall of the event may elicit those pieces of information; victims decide where they begin reporting and where they end, and in whatever order it happens for them. The idea is to gather the pieces of information, whether they are very fragmented or not, without interrupting victims. The team observed that even if told that chronology is not important, victims do tend to report the event in a certain chronological order, simply because everyone has this habit in everyday life of telling a story in a certain order. In this phase, there are no instructions, nothing to influence victims’ concentration or to search for information in one direction or another.

Phase 3: Focused Recall of Sensations

Phase 3 of the CI-AT checks whether additional information can be elicited by inquiring about memories for each particular sensory modality, as well as internal experiences of emotions, thoughts, or bodily feelings. This tends to elicit additional central details, i.e., where attention was focused and significance attributed during the attack. These details may or may not be relevant to the investigation. They are generally more strongly and enduringly stored in memory and less vulnerable to distortion than peripheral details that had little or no attention or significance to the victim’s brain at the time.

Given non-leading prompts, the victim attempts to access memories of the event by prioritizing one sense at a time (e.g., “What if anything do you recall hearing?”) and reports any new information that comes to mind. It’s sometimes surprising to discover a piece of information attached to a particular sense that, on the face of it, did not seem likely.

Also, a victim may have unintentionally omitted an important detail but then recall it while concentrating on a particular sensory modality or internal experience of thoughts or feelings.

From Phase 3 onward, investigators can ask some “time- and context-sensitive questions,” also called “compatible questions,” i.e., the right question, at the right time, while an interviewee is “there” in their mind attending to a particular aspect of the event and any recalled sensations, thoughts, and feelings associated with it. For example, if a victim is able to do so, the investigator might ask them to describe in more detail bodily sensations while they are already reporting and concentrating on them because some could help establish elements of the offense. In this phase of recall, it is common for victims to describe their experience of the assault in a very detailed and visceral way. In the case of sexual assault, non-consent is often made even clearer by recounting the sensory and emotional experience with this degree of detail and intensity. Relatedly, only a video recording of the interview, especially for such portions, can accurately represent the victims’ experience.

Phase 4: Key Segment Review

Phase 4 is probably the most familiar to investigators. It involves going over segments of the event that are most important to the investigation. Investigators must prioritize the segments that need to be clarified. Asking victims to draw a sketch of the scene may also help the victim to recall information. It is in this phase that investigators may ask, if the victim is “able to,” to describe more specific elements related to the crime, for example, the description of a vehicle, a weapon, or the suspect. By this point in the interview, victims are more likely to be tired, and their memory may be less accessible. The ability to concentrate, which can be impaired by stress, waves of intense emotional experience, and emotional or physical fatigue—generally diminishes as the interview progresses. The number of segments to be checked should therefore be reasonable.

The CI-AT’s sequencing of the three ways of eliciting memory recall is important. Once the request for recall is guided toward a focus on sensations, thoughts, feelings, or on particular segments of the event, the opportunity for a totally free recall has ended, hence the importance of not changing the order of the phases.

If several events are the subject of a complaint, for example in a domestic violence or human trafficking context, the victim may choose to report the three most significant victimizations, concentrating on one at a time and using each of the recall phases. The abusive relationship history or history of being trafficked by a particular offender or organization can also be added.

The rule of non-suggestive questioning in police interviewing remains essential. In addition, the trauma-sensitive approach recommends being very attentive and formulating questions in ways that reduce the possibility of a victim feeling judged. Among other things, questions about the clothing worn during the sexual assault and about alcohol and drug consumption are particularly sensitive. In CI-AT training, investigators are taught to anticipate discomfort. They are encouraged to slow down, and to take time to formulate questions properly, to explain the purpose of a sensitive question. Above all, they are taught to avoid “why” questions, which are easily perceived as blame and judgment.

Phases 5–6:Consultation and Conclusion

The recall phases are followed by Phase 5, which involves a systematic consultation with a colleague, who is usually assisting the interview from the control room, to make sure the essential elements of the offense are covered, and anything else needing clarification is addressed. Finally, in Phase 6, the interview concludes with a focus on the victim’s well-being.

Benefits of a Cognitive Interview Adapted to Stress and Trauma

The aim of victims’ police interviews remains as always—to obtain information for a proper investigation.

Essential to CI-AT training are the basics of the neurobiology of severe and traumatic stress. Learning these enables interviewers to better understand victims’ thinking and behaviors during assaults, as well as their memory encoding, storage, and recall. The teaching on common impacts of severe and traumatic stress on the brain’s defense circuitry10 and prefrontal cortex and the commonly resulting impairments of thinking, reflexive reactions, and habit behaviors (e.g., tonic immobility11 and collapsed immobility)12 , as well as altered memory process, all foster greater intellectual and emotional understanding of victims’ experiences. This greater understanding helps interviewers to distance themselves from common myths and biases associated with sexual assault. Bias and lie-seeking in a victim interview negatively affect the investigator-victim dynamic and the elicitation of information and can possibly revictimize the victim.

Notes:

1Hopper, J.W. https://jimhopper.com/online-courses/

2Hopper, J. W. (2022). Website section on “Sexual Assault & the Brain,” https://jimhopper.com/topics/sexual-assault-and-the-brain/

3EVAWI – End Violence Against Women International https://evawintl.org/olti/

4EVAWI – Hopper, J. W., Lonsway, K. & Archambault, J. (2020). Important things to get right about the neurobiology of trauma, Part 1. Benefits of understanding the science. End Violence Against Women International. https://evawintl.org/wp-content/uploads/TB-Trauma-Informed-Combined-1-3.pdf

5Fisher, R.P. & Geiselman, R.E. (2014). The cognitive interview method of conducting police interviews: eliciting extensive information and promoting therapeutic jurisprudence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 33 (5-6), 321-328.

6Fisher, R.P. & Geiselman, R. W. (2019). Expanding the cognitive interview to non-criminal investigations. In Evidence-based investigative interviewing. Edited By Jason J. Dickinson, Nadja Schreiber Compo, Rolando N. Carol, Bennett L. Schwartz, Michelle R. McCauley.

7Dodier, O., Ginet, M., Teissedre, F., Verkampt, F. & Fisher, R. (2021). Using the cognitive interview to recall real-world emotionally stressful experiences: road accidents. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35: 1099-1105.

8Diamond, D.M., Campbell, A.M., Park, C.R., Halonen, J. & Zoladz, P.R. (2007). The temporal dynamics model of emotional memory processing: A synthesis on the neurobiological basis of stress-induced amnesia, flashbulb and traumatic memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Neural Plasticity. doi:10.1155/2007/60803

9Flowe, H.D., Jores, T., Gawrylowicz, J., Hett, D. & Davies, G.M. (2021) ‘Impact of alcohol on memory: a systematic review’. In: H.D. Flowe & A. Carline (eds.) Alcohol and remembering rape: new evidence for practice. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp. 33-69. DOi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67867-8_3

Please cite as

Jennifer Chez and Lynne Bibeau, “Trauma-Informed Interview Adaptations: The Rationale and Procedure for a New Structured Police Investigative Interview,” Police Chief Online, December 24, 2025.