Women are underrepresented in law enforcement in the United States, representing less than 13 percent of full-time sworn officers and a much smaller percentage (3 percent) of persons serving in police leadership positions.1 Estimates of women in the supervisory and management ranks indicate that, in large police agencies, women currently hold 7.3 percent of top command positions (chiefs, assistant chiefs, commanders, and captains), 9.6 percent of supervisory positions (lieutenants and sergeants), and approximately 2 percent of all chief of police positions.2

Research on the benefits of women in policing is clear. Studies indicate that women have stronger relationships with the community and demonstrate greater empathy and interpersonal communication skills.3 Women also tend to be more motivated to serve their communities. Women officers are less likely to use force, and they use less excessive force. They also adopt less confrontational styles in their interactions.4 Studies have found women can have a calming effect on male police partners in high-stress situations.5 Female officers are named less frequently in citizen complaints and lawsuits.6

Despite efforts to increase representation and evidence confirming the benefits of women in policing, the percentage of women in policing has remained relatively stagnant over the past few decades.

Representation and Advancement in the NYPD

The representation of sworn women in the New York City Police Department (NYPD) is currently 19 percent, a 3 percent increase since 2000.7 Overall, women comprise 17 percent of sergeants, 13 percent of lieutenants, and 11 percent of those in the executive ranks (captain and above.) Of the nearly 7,000 females (out of approximately 34,500 officers) in the NYPD, 11 percent have advanced to sergeant, 3 percent are lieutenants, and just over 1 percent are executives. By comparison, of the approximately 27,500 males, 13 percent have advanced to sergeant, over 5 percent to lieutenant, and nearly 3 percent are executives. Though not dictated by civil service, it is also interesting to note that males make up 85 percent of the detective rank in the NYPD.

The qualifications (e.g., time in rank, college credits) and process for promotions vary across police agencies. Eligibility may vary by rank; for example, in the NYPD, an officer must complete 64 college semester credits to be promoted to sergeant, 96 credits to attain the rank of lieutenant, and a bachelor’s degree for promotion to captain. Beyond the initial eligibility requirements, the promotional process for sergeant, lieutenant, and captain in the NYPD consists of a written civil service exam. The multiple-choice exam primarily asks questions about department policies, procedures, and legal issues. Many employees spend several months studying for an exam and attending costly test preparation classes. Applicants utilize their own time, including vacation and other accrued time, to prepare for the exam. Like many agencies, the stakes are high, as it can be many years between exams. This may demoralize officers who missed a cutoff date and have to wait years for the next exam. Some may have significant life changes (marriage, children, etc.) during this period that may affect the decision to take an exam. The most recent sergeant exam in the NYPD was in August 2022; the two prior were in 2017 and 2013. In addition, it can be several years between an exam and a promotion, depending on civil service list placement, and historically, some lists had expired before all those who passed were promoted. Given the reliance on periodic civil service testing, the ascension of officers to the upper ranks of the NYPD can be a slow progression.

The Decision to Advance

Research on advancement among women police officers is limited, though this topic has gained more attention since the 2018 National Institute of Justice Research Summit on Women in Policing.8 Existing studies indicate that deciding to advance one’s policing career can be significant, especially for women. Factors influencing officers to participate in the promotional process include greater career opportunities, salary, personal goals, and a desire to be in a leadership role.

Barriers may be internal and external and affect women differently, especially when considering the officer’s race and ethnicity.9 Previous research attributes the lack of females being promoted to personal and organizational factors, including family obligations and concerns, working patterns/schedules, tokenism, bias and discrimination, sexual harassment and other misogynistic behavior, expectations, lack of support, lack of mentoring, lack of representation, the relegation of female officers into “female jobs,” and organizational culture and environment.10

Research comparing males and females show similarities and differences in the factors influencing the decision to pursue a promotion. Family needs (i.e., childcare and change of shift) are a far more critical factor for women than men.11 Studies have also indicated that gender differences begin to appear with an increase in years of service, with females being less likely to aspire to promotion over time. Female police officers have noted a lack of role models as a motivating factor. In comparison to females, males rarely cite bias as a factor. Research has also indicated that females believe they may face resistance from male peers within their organization if they choose to participate in the promotion process.12 The limited research on the impact on the career progression of female police officers of being married to another police officer has mixed results.

The present study aims to expand knowledge on officers’ career advancement, specifically for female sergeants. This study intentionally focused on the rank of sergeant, as this is the critical first step in advancement. A series of focus groups were conducted with women sergeants to inform the design of the survey questions. Focus group participants were asked questions about past and future participation in the promotion process, and why (or why not) they made the decision to participate. Qualitative findings suggest that women sergeants are motivated to seek promotion even though their likelihood to advance has remained relatively fixed over time. Few participants had never elected to take the lieutenant exam, and most had taken multiple exams. Dominant themes that arose during the focus groups included culture, flexibility, schedule, seniority, work-life balance, and “working mom guilt.” The focus group participants noted that finding time to prepare, expensive classes, and lack of incentives were primary considerations when deciding whether to take the lieutenant exam. Lack of time coupled with guilt over family priorities are barriers that most females believe can be avoided only if rank advancement is sought while young and new on the job. They noted that motivation changes when “life happens.”

To compare males and females, the research team administered identical surveys to both groups of sergeants. The survey asked about their motivation to take a promotional exam, sources of encouragement and support, influential decision factors, and challenges faced. The response rate was substantial for both cohorts: 325 females (45 percent) and 1,616 males (42 percent) completed the survey.

The findings were consistent with extant research and information obtained during the focus groups. Over 80 percent of female and 75 percent of male respondents reported taking a lieutenant exam, and over 60 percent of both cohorts had taken two or more exams. Over 60 percent of all respondents had failed their most recent exam, while approximately one-third of both cohorts were on an active promotional list.13 When asked if they were planning to retire at the rank of sergeant, males were more likely than females to report in the affirmative. Women were more likely to say “not sure.”

When asked about encouragement by supervisors to take exams, slightly over 50 percent of females reported feeling encouraged by supervisors to take exams compared to 57 percent of males. Both groups felt support to prepare for exams was more likely to come from home than from their supervisors. Males reported greater support from home than their female counterparts (76 percent vs. 68 percent).

Respondents were asked “What do you consider the most influential factor for taking the exam?” For both groups, the most influential factors were money/pension, career advancement, and personal achievement. Males are much more likely to be influenced by money/pension (53 percent vs. 39 percent) and quality of life issues (9 percent vs. 4 percent) than females. Females reported career advancement (25 percent vs. 19 percent) and personal achievement (24 percent vs. 12 percent) as greater influences.

In helping to advance to a higher rank, respondents from both groups noted that test preparation, followed by family support, were the most important factors. Females reported in-service training, role models, networking, peer support, and mentorship as more important in helping to advance to a higher rank than males rated them.

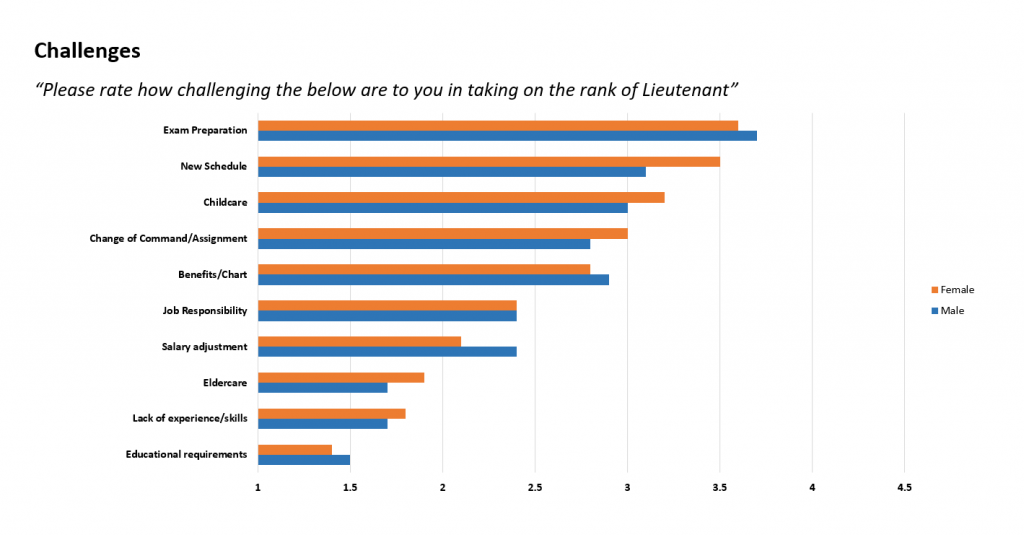

Respondents were asked about perceived challenges in taking on the rank of lieutenant. Both groups identified exam preparation, new schedule, childcare, and change of command as either very or extremely challenging. Males reported salary adjustment and benefits as more challenging than females, likely due to projected loss of overtime. Females reported eldercare and lack of experience or skills as a challenge more so than males.

Respondents were asked about perceived challenges in taking on the rank of lieutenant. Both groups identified exam preparation, new schedule, childcare, and change of command as either very or extremely challenging. Males reported salary adjustment and benefits as more challenging than females, likely due to projected loss of overtime. Females reported eldercare and lack of experience or skills as a challenge more so than males.

In sum, the study found that female sergeants in the NYPD do desire and actively seek promotion to the rank of lieutenant. While males and females find exam preparation equally challenging, females report greater lifestyle issues while males report monetary matters.

In sum, the study found that female sergeants in the NYPD do desire and actively seek promotion to the rank of lieutenant. While males and females find exam preparation equally challenging, females report greater lifestyle issues while males report monetary matters.

Moving Forward

Policing has been a male-dominated profession since its inception. While the profession has made strides in the number and percentage of women in policing, women remain underrepresented in law enforcement across the globe. There are personal, professional, and structural barriers that affect women’s recruitment and advancement in law enforcement agencies. Identifying and understanding these barriers, and those that may be specific to each agency, are essential to the progression of the profession.

The NYPD was one of the first agencies to join the 30×30 Initiative to advance the representation and experiences of women in policing agencies across the United States.14 The agency’s first female police commissioner, Keechant L. Sewell, was appointed in 2021. The NYPD’s two most recent recruit classes, July 2022 and December 2021, were 28 percent and 26 percent female, respectively. While the NYPD has made progress, there is more work to be done and the agency continues to explore ways to recruit, support, advance, and retain more women in the NYPD and in policing in general.

What can agencies do? Law enforcement agencies need to focus on recruiting, retaining, and promoting a more representative number of female officers. Agencies cannot truly represent the communities they serve with the small percentage of women currently in policing. Representation matters—and not just in the overall workforce—women need to be visible in supervisor and executive ranks as well. Law enforcement agencies should examine data on the demographics of their officers, assess their sentiment around career advancement, and identify challenges, whether unique to their agencies or prevalent in the wider context. 🛡

Notes:

1Shelley S. Hyland and Elizabeth Davis, Local Police Departments, 2016: Personnel (Washington DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2016); Lynn Langton, Women in Law Enforcement, 1987–2008 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010).

2Dorothy Moses Schulz, Breaking the Brass Ceiling: Women Police Chiefs and Their Paths to the Top (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2004).

3Natalie Todak, “The Decision to Become a Police Officer in a Legitimacy Crisis,” Women & Criminal Justice 27, no. 4 (2017): 250–270; W. Dwayne Orrick, Best Practices Guide: Recruitment, Retention, and Turnover of Law Enforcement Personnel (Alexandria, VA: Smaller Police Departments Technical Assistance Program, International Association of Chiefs of Police, 2008).

4National Center for Women and Policing, Equality Denied: The Status of Women in Policing, 2001 (Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Women and Policing, 2002).

5Christine Jacqueline Johns, “Effects of Female Presence on Male Police Officers’ Shooting Behavior” (master’s thesis, Michigan State University, 1976).

6Kim Lersch, “Exploring Gender Differences in Citizen Allegations of Misconduct: An Analysis of a Municipal Police Department,” Women & Criminal Justice 9, no. 4 (1998): 69–79; Kim Lersch and Tom Mieczkowski, “Who Are the Problem-Prone Officers? An Analysis of Citizen Complaints,” American Journal of Police 15, no. 3 (September 1996): 23–44.

7New York City Police Department, “Personnel Demographics Dashboard,” Reports and Statistical Analysis.

8 National Institute of Justice (NIJ), Women in Policing: Breaking Barriers and Blazing a Path (Washington, DC: NIJ, 2019).

9Jihong Zhao, Ni He, and Nicholas P. Lovrich, “Pursuing Gender Diversity in Police Organizations in the 1990: A Longitudinal Analysis of Factors Associated with the Hiring of Female Officers,” Police Quarterly 9, no. 4 (December 2006): 463–485.

10Marisa Silvestri, Stephen Tong, and Jennifer Brown, “Gender and Police Leadership: Time for a Paradigm Shift?” International Journal of Police Science & Management 15, no. 1( March 2013): 61–73.

11Thomas S. Whetstone, “Copping Out: Why Police Officers Decline to Participate in the Sergeant’s Promotional Process,” American Journal of Criminal Justice 25, no. 2 (March 2001): 147–159.

12Carol Archbold and Kimberly D. Hassell, “Paying a Marriage Tax: An Examination of the Barriers to the Promotion of Female Police Officers,” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 32, no. 1 (March 2009): 56–74.

13Promotional exams for NYPD lieutenant were given in 2015 and 2017; the next one is scheduled for early 2023.

14 See the 30×30 Initiative’s webpage “About 30×30” for more information and to join the initiative.

Please cite as

Tara Calabro and Tanya Meisenholder, “Beyond Recruitment: Barriers to Promotion among Women in Law Enforcement,” Police Chief Online, January 4, 2023.