Each day, in towns and cities across the United States, law enforcement officers and civilian professional staff serve their communities in countless ways. Irrespective of the issue at hand—be it an emerging or active threat, a volatile domestic dispute, a traffic stop, an investigative interview, or simply answering a question—timely, precise, and effective communication is essential to ensure that the matter in question is successfully resolved.

Among the many challenges law enforcement officers and professional staff face are those inherent in efforts to effectively communicate with and address the needs of all community members, including individuals who are either limited English proficient (LEP), or d/Deaf or hard of hearing (d/D/HH).

In the context of LEP persons, one generally accepted definition of “effective communication” is set forth as follows: “Communication sufficient to provide the LEP individual with substantially the same level of access to services received by individuals who are native speakers of English.”1

Ensuring sufficient communication and equitable service to community members across language barriers is understandably challenging for many agencies; however, there are promising practices for agencies to emulate, including the Portland, Oregon, Police Bureau Language Justice Program.

Legal Requirements

U.S. Federal law—as codified in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and in Presidential Executive Order 13166 (issued in 2000) on Improving Access to Services by Persons with Limited English Proficiency—requires that all agencies receiving federal funding enact policies and develop language access programs designed to address the needs of LEP community members.2 Additionally, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires public accommodations (e.g., law enforcement agencies) to provide auxiliary aids and services to ensure effective communication with d/D/HH persons.3

To ensure that their departments are in compliance with applicable federal laws and to afford all community members the opportunity to communicate effectively with department members, police executives are responsible for developing and maintaining language access policies, procedures, and practices tailored to the demographic makeup and specific needs of their respective communities.

The development and implementation of effective language access plans are complex tasks that can present significant challenges to many police departments. These challenges are exacerbated by other, equally problematic realities, including staffing shortages, rising crime rates, and an erosion of community trust brought about by shifting socio-political and cultural attitudes.

IACP Trust Building Campaign

In 2022, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) launched its Trust Building Campaign, which strives to “enhance trust between police agencies and the communities they serve by ensuring positive community police partnerships that promote safe, effective interactions; create strategies to prevent and reduce crime; and improve the well-being and quality of life for all.”4

The development and implementation of a robust police language justice program aligns perfectly with the Trust Building Campaign’s objectives. Such programs honor the spirit of civil and criminal rights by ensuring that access to and navigation of the criminal justice system are afforded to persons facing language barriers. Additionally, successful application of an efficacious language access program fosters trust between law enforcement departments and historically marginalized LEP communities.

The development and implementation of a robust police language justice program aligns perfectly with the Trust Building Campaign’s objectives. Such programs honor the spirit of civil and criminal rights by ensuring that access to and navigation of the criminal justice system are afforded to persons facing language barriers. Additionally, successful application of an efficacious language access program fosters trust between law enforcement departments and historically marginalized LEP communities.

According to the 2019 American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 13 percent of persons in the United States over five years of age speaks English “less than well,” and 6 percent speak English “not at all.”5 It is noted that this estimate represents information culled only from census respondents; numerous researchers have pointed out transitory, migrant, and undocumented immigrant populations within the United States are significantly under-represented in the census figures. For the purposes of this article, persons in the United States who speak English “less than well” and LEP individuals constitute the same population.

With respect to d/D/HH and deafblind communities, estimating numbers of U.S. persons who fall into those categories is complicated by privacy regulations, including those imposed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

However, estimates of d/D/HH populations can be inferred from the results of the 2022 U.S. Census survey reflecting that approximately 11.5 million persons residing in the United States (about 3.5 percent of the population) have varying degrees of hearing difficulties.6

The foregoing statistics suggest that, at some point in the course of carrying out their assigned duties, police officers across the United States are likely to encounter LEP and d/D/HH community members. During such interactions, both officers and LEP and d/D/HH persons must be able to effectively communicate with one another. Furthermore, officers must have confidence in their ability to successfully discharge their responsibilities while engaging with members of these communities, while LEP and d/D/HH persons must believe that they can accurately convey the nature and extent of their concerns to responding officers.

The foregoing statistics suggest that, at some point in the course of carrying out their assigned duties, police officers across the United States are likely to encounter LEP and d/D/HH community members. During such interactions, both officers and LEP and d/D/HH persons must be able to effectively communicate with one another. Furthermore, officers must have confidence in their ability to successfully discharge their responsibilities while engaging with members of these communities, while LEP and d/D/HH persons must believe that they can accurately convey the nature and extent of their concerns to responding officers.

Research suggests that limited English-language proficiency or a lack of cultural familiarity are not the only factors that affect communication between LEP persons and U.S. law enforcement personnel. Both anecdotal accounts and academic research indicate that immigrant crime victims or justice-involved persons often distrust police officers and the U.S. justice system for a variety of reasons that might not be evident to responding officers, including generational trauma and personal experience with police abuse in their home countries. In addition, these individuals often lack knowledge about their civil rights under U.S. law and are unaware of the various legal processes and systems in place to serve LEP justice-impacted persons.7

Given the statistical likelihood that officers will, at some point in their careers, engage with LEP or d/D/HH community members, it is imperative that officers are made familiar with and remain cognizant of the legal, ethical, and procedural ramifications associated with a departmental failure to ensure equal access to language assistance and qualified interpretation. Numerous case examples have demonstrated that LEP suspects who are not provided Miranda warnings in their native language can and have successfully challenged criminal prosecutions on the basis that the suspects were not afforded access to qualified interpreters and thereby were denied their civil rights.8

Given the statistical likelihood that officers will, at some point in their careers, engage with LEP or d/D/HH community members, it is imperative that officers are made familiar with and remain cognizant of the legal, ethical, and procedural ramifications associated with a departmental failure to ensure equal access to language assistance and qualified interpretation. Numerous case examples have demonstrated that LEP suspects who are not provided Miranda warnings in their native language can and have successfully challenged criminal prosecutions on the basis that the suspects were not afforded access to qualified interpreters and thereby were denied their civil rights.8

Any perception that a department is either deliberately ignoring or willfully imposing barriers between an investigative subject and their civil rights with respect to language access can only serve to erode public trust in that department’s policing efforts.

Conversely, initiatives that highlight a department’s commitment to better serve the different constituencies within their community, including those facing language obstacles, demonstrate that department’s focus on improved services, community engagement, and a collective interest in better fulfilling its law enforcement and civic responsibilities.

Evolution of the Portland Police Bureau Language Justice Program

The Portland Police Bureau (PBB) created a policy in 2013 that guides officer and staff interactions with LEP and d/D/HH persons; however, the true genesis of PPB’s Language Justice Program dates back to 2017, when PPB’s Office of Community Engagement (PPB/OCE), in cooperation with the National Immigrant Women Advocacy Project and the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence , prioritized introducing language-related training and education to bilingual PPB members and colleagues from other Portland-area law enforcement agencies.9 Although policy is a critical component of the process of establishing a language justice program, the PPB/OCE recognized that ensuring that bilingual officers and staff receive proper instruction to appropriately equip them to provide effective interpreter services was also foundational to building a functional program that adequately served communities facing language barriers.

Over the course of the years that followed, PPB continued to build its Language Justice Program, despite unforeseen challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, that disrupted its ability to implement a robust internal program. Notwithstanding these impediments, PPB maintained engagement in the process, both to ensure that it met its responsibilities under the law and to institutionalize equitable and accessible language justice practices to more effectively serve the community.

Over the course of the years that followed, PPB continued to build its Language Justice Program, despite unforeseen challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, that disrupted its ability to implement a robust internal program. Notwithstanding these impediments, PPB maintained engagement in the process, both to ensure that it met its responsibilities under the law and to institutionalize equitable and accessible language justice practices to more effectively serve the community.

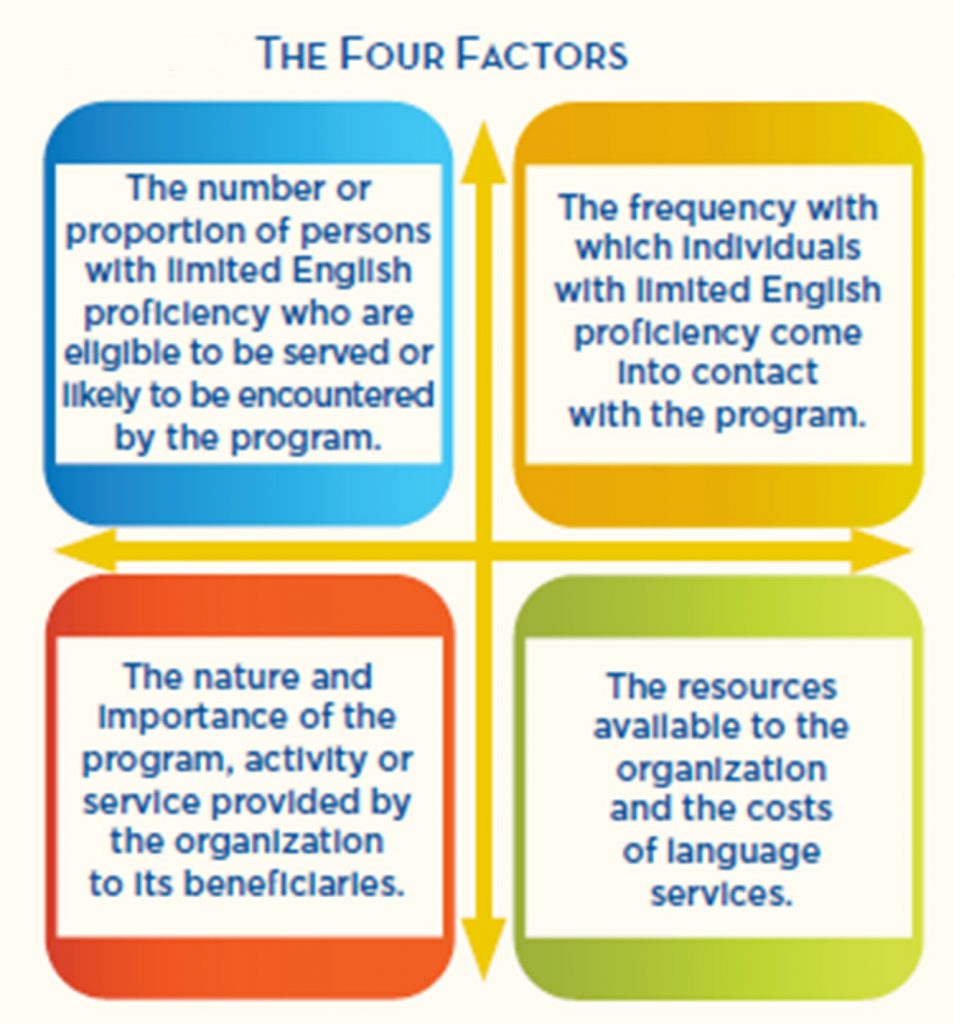

Presidential Executive Order 13166, Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency, mandates that any agency receiving federal financial assistance must (1) ensure meaningful language access and (2) develop and implement language access plans. Mindful of this mandate, PPB implemented a four-factor analysis to build internal policy, training, and procedures for members who engage in crisis and non-crisis interactions with the LEP and d/D/HH communities.10

Four-Factor Analysis

|

| Source: Guide to Developing a Language Access Plan |

An agency’s obligation to provide language-assisted services is determined on a case-by-case basis, based on an assessment that balances the following four factors:

-

- the number or proportion of LEP persons served or encountered in the eligible service population

- the frequency with which LEP persons come in contact with the program

- the nature and importance of the service or benefit provided by the program

- the resources available to the agency and the costs of those resources

Number of Persons Served

PPB used existing data platforms to map the scope and demographics of LEP communities in Portland. Such data analysis proved to be of critical importance in the development of a tailored Language Justice Program. Of note were data provided by the Migration Policy Institute, indicating that in 2020, approximately 50 percent of foreign-born Oregon residents spoke English less than well; additionally, the 2022 Portland Public Schools statistics reflected that more than 100 languages are spoken by its students.11

Frequency of Contact

PPB’s Strategic Services Division analysts evaluated 911 dispatch center calls and determined that, in 2017, emergency calls from throughout the Portland metro area necessitated language assistance in more than 30 languages and dialects. The analysts continue to collect and evaluate data on usage of Language Line and other contracted interpreter resources by both patrol officers and investigators. Such analysis assists PPB executives responsible for developing and implementing strategic engagement policies.

Services Provided

In addition to informing PPB executive management decisions on strategic engagement policies, analysis of language-related data, including 911 calls and Language Line and contracted interpreter resources, is a vital component of the agency’s efforts to identify the type and frequency of calls for service occurring in LEP communities. Such efforts allow for tailored community outreach, education, and focused crime prevention.

Resources

PPB’s focus on language-related data and evidence-driven decisions led to the development of various internal language resources for patrol officers and investigators. In 2019, PPB surveyed its members to assess its internal language capacity and to inform the development of a formal PPB staff interpreter program. Survey results indicated that PPB members (survey participants) speak more than 30 languages. Recognizing an opportunity to both build trust with impacted communities and support members and enhance their skillsets, PPB’s chiefs allocated funding for members to use Rosetta Stone. The immersive language learning tool serves as a simple affordable means by which PPB members can improve their language proficiency and, thereby, better serve LEP and d/D/HH persons.

Furthermore, PPB also engages its culturally and linguistically specific advisory councils, e.g., the Portland-based Slavic Advisory Council, as resources. The councils provide an opportunity for PPB members to interact with council participants to practice their language skills, and these advisors serve as conduits to LEP communities.

Language Justice vs. Language Access

In 2020, the American Bar Association (ABA) (americanbar.org) published an article entitled, “Language Justice During Covid-19” in which the ABA describes language justice as an evolving framework, as well as a “commitment to ensuring individuals marginalized based on their national origin, ethnic identification, and language are not denied equal access to service, remedies, and justice overall.”12 This concept of language justice is squarely in line with PPB procedural justice tenets and policies, so, in 2021, PPB/OCE, as part of its continuing efforts to promote public trust in policing and enhance police legitimacy and accountability, pivoted from its original approach of creating a language access program to building a more inclusive and wide-ranging language justice program. As the ABA article conveys, language access is an important component of ensuring effective communication, but it is only one piece of the puzzle.13 Language justice is the complete puzzle—a comprehensive and systematic approach to serving LEP and d/D/HH communities that extends beyond merely providing access to communication tools.

Policy Re-development

As a result of extensive collaboration with PPB’s Policy Team, PPB/OCE developed holistic, comprehensive language justice policies that applied the four-factor analysis; incorporated input from various internal and external stakeholders, including members of the LEP and d/D/HH communities, bilingual PPB staff, and other local and state language advocates; and centered on the specific language needs of Portland’s LEP and d/D/HH communities. In furtherance of these efforts, PPB/OCE sought assistance from PPB Strategic Services Division analysts as a means of facilitating data- and evidence-driven program development.

Training

In developing the Language Justice Program, PPB/OCE worked closely with PPB’s Training Division to create a series of training videos focused on language and cultural awareness. Through innovative community engagement, PPB sought and obtained the participation of Portland-based subject matter experts and persons with relevant lived experience to appear in the videos. These individuals provided valuable insights and personal testimonials concerning their encounters with law enforcement officers and the justice system.

Engaging community partners and community-based subject matter experts in the process of developing police training, policy, and procedure, while fostering trust with communities, reflects the spirit of the language justice and goes beyond addressing the “access” framework. Language justice is an area of police training that allows for robust community integration and participation. Law enforcement agencies do not have the level of expertise on the cultural and linguistic needs of LEP and d/D/HH communities that the communities themselves have. Coordinating and collaborating with the LEP and d/D/HH communities to inform police training aids law enforcement agencies in better understanding these communities’ needs.

In one video, a Somali refugee mother, Salado, spoke of the many integration and acculturation challenges she has faced as an immigrant, including a significant language barrier. She recounted an incident when her minor child went missing, after which responding PPB patrol officers successfully utilized departmental language resources to establish timely and accurate communication with Salado and her family. As a result of that interaction, Salado states in the video, “The PPB is my friend now. I am not as afraid of the police as I used to be.”

A Language Justice Program Roadmap–The PPB Model

Effective communication is critical to successfully performing most law enforcement duties. It affects safety and impacts outcomes. Law enforcement executives have a legal responsibility to ensure that their agencies comply with federal laws pertaining to language access, but developing and maintaining comprehensive policies and practices is also the principled thing to do.

To follow are six key takeaways for executives seeking to create or transform their agencies’ language justice practices.

-

- Assess Internal Resources and Capacity

In 2019, for the first time in its history, PPB disseminated an agency-wide survey in order to assess departmental language capabilities and officers’ willingness to provide interpretation services as needed. The survey results continue to serve as a valuable metric that informs PPB leaders’ decision-making regarding policy, training, and the allocation of resources to support its language justice program.

-

- Community Engagement Strategies and Partnerships

PPB is committed to and actively pursues the design, development, and incorporation of holistic and innovative community engagement strategies. These strategies are specifically tailored to address the needs of the socio-culturally disparate communities PPB serves. As a result, PPB has partnered with a variety of culturally and linguistically diverse community-based organizations as part of its continuing efforts to identify how best to serve the LEP communities within its jurisdiction.

-

- Data Analysis

In its ongoing efforts to assess community language needs and forecast the frequency of future interactions between department members and LEP and d/D/HH persons, PPB works with data from a variety of sources, including the U.S. Census Bureau, relevant school districts, the U.S. Bureau of Labor, and others.

-

- Policy Development

PPB has committed to re-developing its language justice policies through a community-focused lens to establish comprehensive procedures that are clear to officers and meet the needs of community members. The relevant policies inform training and provide a well-defined framework for employing various language justice strategies and resources. When developing policy, PPB prioritizes transparency and stakeholder engagement by allowing for internal and public comment on proposed changes during the policy development process. This step in PPB’s process proved to be particularly important during the re-development of its language justice policies, as it afforded the LEP and d/D/HH communities an opportunity to shape the policies that directly impact them.

-

- Police Language Training Curriculum

Law enforcement agencies prioritize officer training in a variety of “hard” tactical skills, including driving, firearms, and defensive tactics to ensure that they can effectively perform certain duties. In order to facilitate effective interaction with LEP and d/D/HH community members, officers must also receive regular training in interpretation (for bilingual officers) and instruction on how to work with interpreters and respond to situations involving language barriers (for monolingual officers). In other words, language skills are tactical skills that require similar prioritization and resource allocation as other tactical skills.

-

- Program Evaluation

The success of any language justice program is contingent in part on regular, focused analysis of relevant language-related data, coupled with input and feedback from department members and community stakeholders. Such evaluation is necessary in order for a department to identify gaps and opportunities and to improve its policies and procedures.

Conclusion

Police executives face a never-ending, constantly evolving series of operational and strategic challenges against the backdrop of polarized views on police practices and discussions concerning potential reforms. In this environment, it is vitally important that departments recognize the benefits associated with development and implementation of a robust language justice program. Creation of a language justice program, tailored to the specific needs and demographic profile of the communities it serves, is an achievable goal for any police department. Moreover, the onus for building such a program is not solely on police managers. Instead, engagement with relevant community sectors and stakeholders is both recommended and necessary.

A language justice program conceived and constructed in this manner can lead to more effective service to the community, preservation of community members’ civil rights, and the enhancement of police procedural integrity.

Notes:

1U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Justice Language Access Plan, March 2012.

2 “Guidelines for the Enforcement of Title VI, Civil Rights Act of 1964,” Code of Federal Regulations, title 28 (2011).

3U.S. Department of Justice, Title II Regulations Supplementary Information: Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability in State and Local Government Services (Washington, DC: Department of Justice, 2017).

4IACP, IACP Trust Building Campaign.

5Sandy Dietrich and Erik Hernandez, Language Use in the United States: 2019, American Community Survey Reports, 2022.

6Rebecca Waddingham, “Woman Testifies in Rape Trial,” Greely Tribunal, October 5, 2004.

7William F. McDonald and Edna Erez, “Immigrants as Victims: A Framework,” International Review of Victimology 14, no. 1 (2007): 2; Michael Kagan, “Immigrant Victims, Immigrant Accusers,” University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 48, no. 4 (Summer 2015): 921.

8 People v. Aquilar-Ramos, 86 P.3d 397 (Col. 2004); Waddingham, “Woman Testifies in Rape Trial.”

9National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project (NIWAP), “Language Access Materials for Police and Prosecutors,” NIWAP Web Library, updated October 16,2019; Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence, “Language Access, Interpretation, and Translation.”

10Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, “COPS Office Language Access Policy and Plan.”

11Migration Policy Institute, “State Immigration Data Profiles—Language & Education, Oregon“; Portland Public Schools, “Language Access Services.”

12Casey Payton et al., “Language Justice During COVID-19,” American Bar Association, May 13, 2020.

13Joann Lee et al., “Language Justice in Legal Services,” Management Information Exchange Journal (Winter 2019_: 1–10; U.S. Department of Justice, “Department of Justice Language Access Plan.”

Please cite as

Ashley Lancaster and Natasha Haunsperger, “Building Community Trust through Language Justice,” Police Chief Online, June 28, 2023.