Overdoses are ravaging the United States. Over the last two decades, more than 750,000 people have died as a result of a drug overdose, and in this same time, overdose deaths involving opioids have increased by almost six times—evidence of both the lethality and availability of these substances.1 For every fatal drug overdose, there are many more nonfatal incidents, representing a devastating and unfathomable number.2 While the world is struggling to contain a global pandemic, the fight against opioid addiction and fatalities continues with even more challenges. In fact, people currently struggling with a substance use disorder (SUD) are finding themselves practicing social distancing and experiencing isolation, increasing the conditions that lead to overdoses and death.3

Police officers are on the front line of responding to frequent drug overdoses and calls for service involving individuals with substance use and co-occurring disorders. Arguably, one of the most notable actions over the last decade was equipping the police with naloxone to reverse opioid-related overdoses. As a result, the police, who are often the first to arrive on the scene of an overdose, are able to save lives, thus improving the health of the community.

In many communities, the police are not content to just walk away after responding to an overdose incident, but instead seek ways to connect individuals who have SUD to treatment and prevention options. Many agencies are partnering with public health officials, treatment providers, and other behavioral health specialists to conduct outreach to individuals after the successful reversal of an overdose. However, information sharing and collaboration can be problematic among these different stakeholders who typically work in silos.

Given the catastrophic nature of the opioid epidemic, which has caused over 70,000 annual deaths in the United States alone, combined with the need to share data to empower communities to implement overdose response strategies, the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (W/B HIDTA) launched the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP) in January 2017.

Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP)

ODMAP is a surveillance system designed to quickly and accurately understand the drug threat in a particular area. The ODMAP user community includes police, fire, emergency medical services personnel, medical examiners, and coroners. ODMAP provides an opportunity for these stakeholders to come to the table, share information, and collaborate on solutions to the opioid crisis in their communities. Many have pointed to ODMAP as a catalyst to inspire information sharing and collaborative efforts that have broken down silos and spurred action to save lives in communities.

ODMAP was developed to address four core issues:

- The absence of nonfatal overdose reporting

- The ability to equitably scale reporting in communities regardless of financial resources

- The facilitation of information sharing across sectors

- The improvement of information sharing across jurisdictions

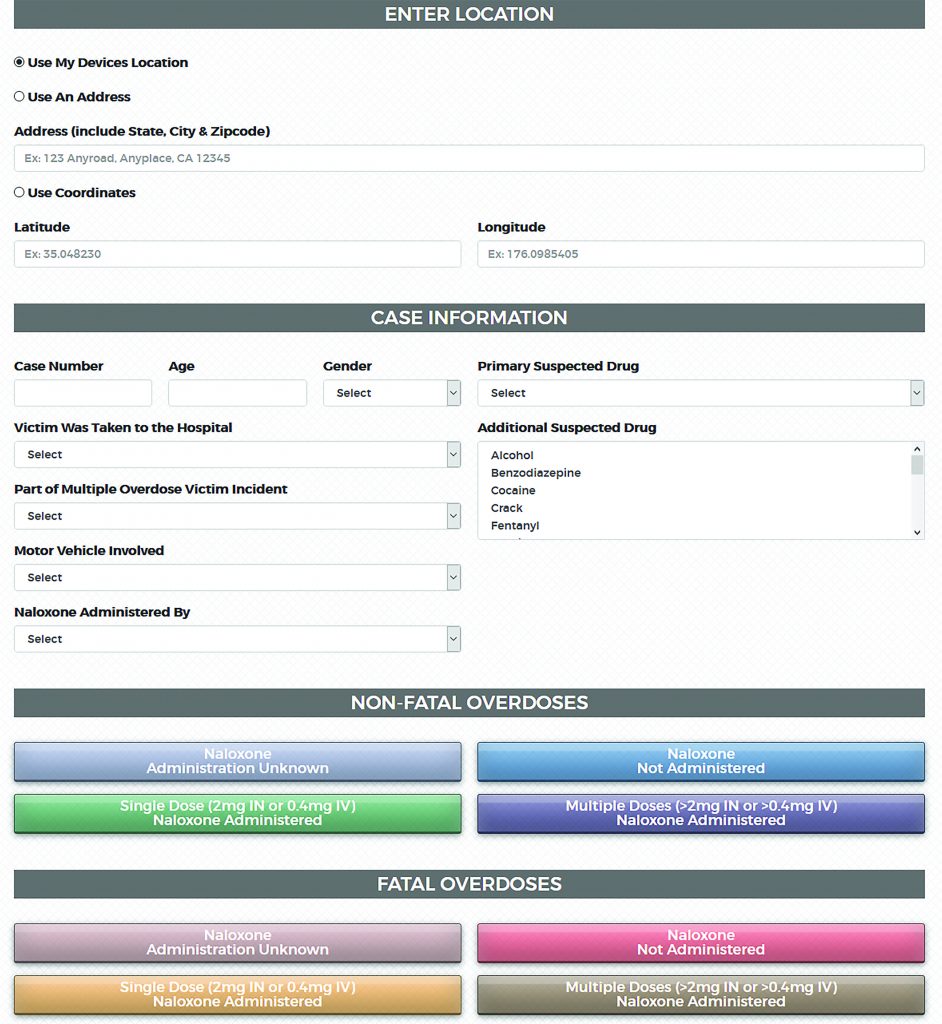

Given the inherent need for timely follow-up to an overdose incident, ODMAP makes data entry easy and quick. The ODMAP application can be accessed on a mobile data terminal in a patrol car, mobile device, or desktop, as long as there is internet access. The interface is easy to use and requires users to fill out only four fields:

- Date/Time

- Location

- Fatality status

- Quantity of naloxone administered

To enable agencies to collect a more robust data set, ODMAP also allows users to submit the following optional information:

- Case number

- Age

- Gender

- Primary suspected drug

- Additional suspected drug(s)

- Whether or not the victim was taken to the hospital

- Whether or not the incident involved multiple victims

- If a motor vehicle was involved

- Who administered naloxone

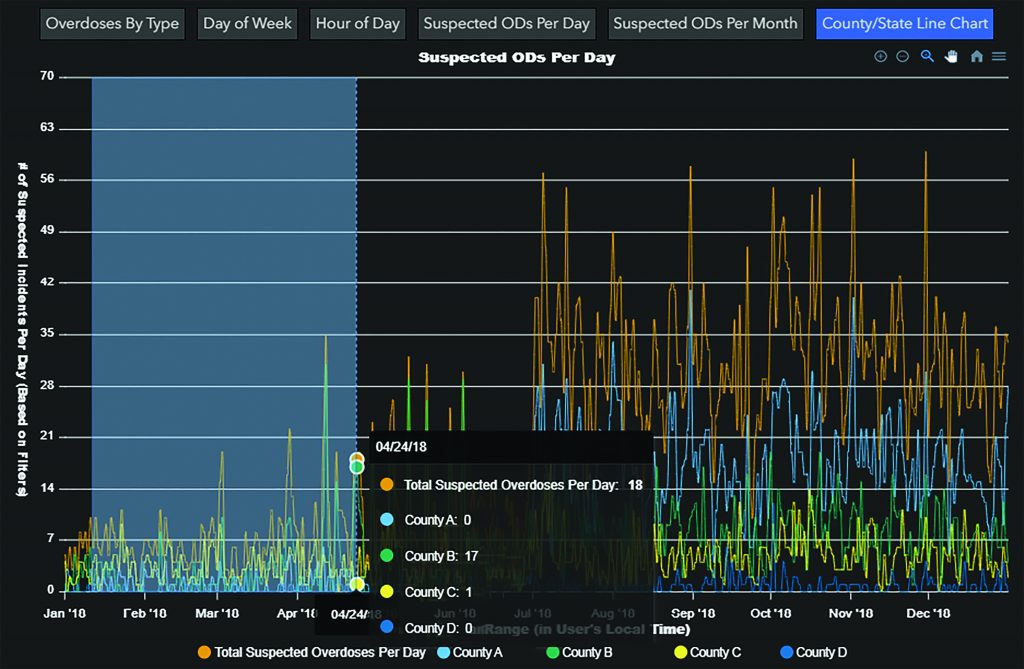

As soon a suspected overdose entry is submitted, it immediately populates on an interactive U.S. map. From the dashboard view, partner agencies have temporal and spatial awareness of overdoses in real time, not only within their jurisdiction, but also in surrounding regions. Separate agencies working together within a jurisdiction, like crisis response or treatment providers, can see overdose cases as they are submitted, creating information sharing where none existed before or bypassing antiquated data-sharing techniques between different actors within communities.

For example, in many instances, first responders will arrive at the scene, gather information, and enter the incident into ODMAP. Public health and other outreach partners monitoring the system will have direct access to this information and can either respond to the scene alongside police to offer support or treatment referrals directly to victims or family members or utilize the map to identify hotspot areas in which to deploy mobile outreach and support services. All data fields can be filtered and manipulated within the platform. The national map also provides additional data visualizations and analysis capabilities, such as incident count charts by overdose type (fatal or nonfatal) and time series analysis tools. Police partners are also able to isolate trends and patterns to better monitor drug trafficking activity to ensure that responding officers have the necessary information to safeguard community members and sufficient naloxone and other resources.

In addition to collaboration, ODMAP can also be a powerful tool for law enforcement intelligence gathering and resource deployment. By utilizing the ODMAP spike alert system and basic time series analysis techniques, agencies can track the origin of overdose clusters. This information can then be used to follow the overdoses as they spread and progress and to aid in identifying drug source locations and their distribution networks. Conversely, ODMAP data can be used to validate suspected drug trafficking routes in the course of an investigation.

ODMAP in Practice: Chesterfield County, VirginiaBy Lt. Timothy Kehoe Like many communities across the United States, Chesterfield County, Virginia, began to face a public safety and public health crisis caused by the heroin/opioid epidemic. When ODMAP was first introduced, the Chesterfield County Police Department (CCPD) recognized it was a tool that could be easily implemented and utilized in varied approaches to address multiple matters. It didn’t take much effort to show county leaders the benefit of ODMAP, and CCPD rolled out ODMAP in mid-2018. As the Vice and Narcotics Unit commander, I serve as the department’s administrator for ODMAP, with assistance from our vice and narcotics analyst. For the first several months of using ODMAP, our narcotics analyst would enter information on suspected overdoses when she reviewed incident reports each morning. Our unit protocol is to send a detective to all fatal overdoses. In cases of nonfatal overdoses, a patrol supervisor would contact the on-call narcotics supervisor either by phone or an email. If the victim was willing to speak to a detective about the source or dealer, we would send out a detective at that time. The problem behind this system was that if patrol knew the victim was unwilling to cooperate, there was no need to call narcotics in the middle of the night, over the weekend, or on holidays, inadvertently leading to a delayed entry of the overdose information into ODMAP.  This changed one weekend in May 2019. After sending a detective to his second fatal overdose in under six hours and having been notified of several nonfatal overdoses during the same timeframe, I responded to another overdose scene along with the detective. While on scene, yet another call for service for a fatal overdose was dispatched. The detective and I took the opportunity on this particular weekend to enter the overdoses into ODMAP at the scene in real time. After entering the other overdoses that evening, we generated our first “spike alert.” We had not seen that many overdoses occur in such a short time period. Concerned for the safety of those suffering from opioid addiction, we sent out a media release that day regarding the spike in cases. We received a tremendous response from our local media. The message we sent out was simple; we wanted the community to know what we were seeing—and we wanted them to know the resources available to them, whether they or someone they love and care for need assistance. While we had our Vice and Narcotics Unit supervisors authorized as Level 1 users, we weren’t using ODMAP as it was intended—for real-time entry. After that weekend, we made a slight change to our operational procedure. We still require notification from patrol of suspected overdoses, but now the on-call narcotics supervisor enters the overdose into ODMAP as soon as notified. By doing this, we know not only when we will get a spike alert, but when we are getting close to one. The spike alerts are a phenomenal tool. Our detectives are on call for a week at a time, so knowing we are in a spike allows us to plan for additional personnel if necessary.  Having real-time access to overdoses and spikes also allows us to notify our other public safety partners, like fire/EMS. Our analysts play a critical role in interpreting data and devising analytical tools like heat maps, but they aren’t available 24/7. ODMAP allows officers, first-line supervisors, and other community partners to see data and maps in real time. One of our local partners, Chesterfield County Mental Health Support Services, employs Lauren Herschler as a full-time opioid outreach coordinator. Lauren serves as a central point of contact for all county agencies involved in battling the heroin/opioid epidemic. Lauren uses the data from ODMAP to respond to cluster and hot spot areas to provide community outreach, like giving Narcan (naloxone) to those at risk of overdosing or handing out information about prevention and health services. Another benefit of ODMAP is the ability to track potential sources of narcotics and even manufacturing operations. Many agencies have seen tremendous success with this aspect of the map. Here in Chesterfield, we know that many drugs like heroin and fentanyl come from source cities up and down the East Coast, as opposed to being manufactured locally. So, while this function does not quite serve our specific needs, it allows us to see trends in our source cities. Whenever we have intelligence or seizures from new source cities or locations, we add those to our list of spike alerts. By tracking spikes in other locations, we can have advance notice of spikes in our own region. |

Police agencies that wish to get the most from the system have the ability to link ODMAP submissions to Case Explorer, a case management system created by W/B HIDTA, which allows for the collection of very detailed information—drug packaging photos; cellphone data; vehicle information; case notes; and suspect, witness, and victim identities. Linking these data to the ODMAP geospatial and temporal data gives investigators the ability to draw much stronger, more robust links between overdoses, supply cities, and drug trafficking organizations.

ODMAP is free of charge and available only to government entities serving the interest of public health or safety, licensed first responders, and hospitals. Interested agencies can request access at www.odmap.org and can log in to the platform as soon as their electronic participation agreement has been executed, which typically takes less than 24 hours. Agencies can enter data, create spike alerts, utilize embedded analytics, and view data submitted from across the United States. ODMAP complements existing surveillance or overdose strategies by supporting near real-time reporting; sharing the data across disciplines to put data into action; and enabling the reporting of county, state, regional, and national trends and patterns.

By sharing data, encouraging collaboration, and propelling data into action, agencies can play a fundamental role in ending the cycle of response, report, and repeat, permitting the reallocation of resources and, most important, saving lives. d

Notes:

1Holly Hedegaard, Arialdi M. Miniño, and Margaret Warner, Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2018, fig.1, NCHS Data Brief no. 356 (Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, 2020).

2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevent and Control, “Nonfatal Drug Overdoses,” April 7, 2020.

3American Medical Association, Reports of Increases in Opioid-Related Overdose and Other Concerns during COVID Pandemic, Issue Brief (Advocacy Resource Center, updated 2021).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please cite as

Aliese Alter, Christopher Yeager, and Timothy Kehoe, “Ending the Cycle of Response, Report, Repeat: Information Sharing via HIDTA ODMAP,” Police Chief 88, no. 4 (April 2021): 58–63.

Aliese Alter is a senior program manager with the Washington/Baltimore HIDTA) and directly oversees the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP) Platform. She is responsible for the overall management of ODMAP, including outreach, program development, implementation, and national partnerships. Prior to joining HIDTA, she served as a sworn officer for six years.

Aliese Alter is a senior program manager with the Washington/Baltimore HIDTA) and directly oversees the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP) Platform. She is responsible for the overall management of ODMAP, including outreach, program development, implementation, and national partnerships. Prior to joining HIDTA, she served as a sworn officer for six years. Christopher Yeager is the ODMAP data research analyst within the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area; he also provides analytical support to partner agencies and acts as a liaison to academic research affiliates. His prior roles include criminal data research analyst for Baltimore, Maryland, and serving as a sworn officer for seven years.

Christopher Yeager is the ODMAP data research analyst within the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area; he also provides analytical support to partner agencies and acts as a liaison to academic research affiliates. His prior roles include criminal data research analyst for Baltimore, Maryland, and serving as a sworn officer for seven years. Timothy Kehoe serves as the Vice and Narcotics Unit commander for the Chesterfield County, Virginia, Police Department. Where he oversees the daily operations of the unit and serves as the agency’s ODMAP administrator. He has also served in a variety of other capacities including uniform operations, special operations, and criminal investigations.

Timothy Kehoe serves as the Vice and Narcotics Unit commander for the Chesterfield County, Virginia, Police Department. Where he oversees the daily operations of the unit and serves as the agency’s ODMAP administrator. He has also served in a variety of other capacities including uniform operations, special operations, and criminal investigations.