Every time a new police chief, sheriff, or other law enforcement leader gets sworn in as a public servant, the community members he or she will serve cannot help but hope for an improvement of their neighborhood. Law enforcement leaders are seen as a trusted broker of the local government’s fiscal resources and the truth-bearers of social inequities, offering progressive maneuvers toward social justice.

As they step into their new role, one of the biggest questions law enforcement leaders face is how do jurisdictions, especially larger cities with diverse demographics, get equitable crime reduction in all neighborhoods? Balancing quality, time, and resources is difficult. Establishing a plan for equitable crime reduction takes courage and more than status-quo leadership. The accomplishment lies in taking personal responsibility to lower crime in all neighborhoods. It lies with clarity of thought and integrity of action, balancing enforcement with community trust building. It lies with sacrifice, with focusing on results and attrition-proofing concepts and deliverables.

Regardless of the agency’s mission, vision, and value statements—and, in deference to any strategic plan, three core elements should always be considered among a law enforcement leader’s priorities.

First is officer safety. This is not just the in-the-moment protection of officers from death or great bodily harm, but the holistic health and welfare of officers through their entire careers. This type of safety goes beyond training and requires proven, intelligence-led processes that start with empowering an “informed officer.”

Second is mission accomplishment. If a model mission statement does not include crime reduction and community involvement, then it is not an accurate law enforcement mission statement. A simplified, actionable mission statement for the 21st century could be “Prevent crime, together.” Those three words can inspire a three-day class—one for each word. By preventing crime, law enforcement is lowering risk to both victims and offenders, not to mention increasing the aforementioned officer safety. Doing it together requires collaboration. It also requires deep trust, which cannot be achieved without openness and transparency.

Third is equitable efforts and equitable outcomes. A good agency leadership and management model will toil over their deployments—not just on occasion, but annually (or even more often). Crime morphs, economies morph, populations morph—all as parts of a complex system of human engagement. By reviewing a deployment model through analyses at least one time per year, the agency is using business intelligence to adapt to the changing needs of the community. For instance, holding weekly planning meetings in October and November can allow any agency to take nine months of current, calendar-year data into consideration, while offering enough pivot time to align with any shift-bidding, expected attrition, and the forthcoming New Year. This ensures the workloads of call taking, crime investigations, and support efforts allow everyone to go home tired, but not dangerously exhausted. On the community side, equitable outcomes mean that the deployment should afford all neighborhoods a chance to lower crime and improve quality of life to a similar level throughout the entire jurisdiction. Too often, there is the “good side of the tracks” and the “bad side of the tracks.” Both sides need equitable outcomes to thrive. The police and the community should be as safe and crime free as possible across the board.

Start with a Plan: Tampa Case Study

In 2002, the crime rate in Tampa, Florida, was 110 percent higher than the statewide average.1 Despite the numbers, the nationally accredited department was full of good, hardworking officers, and, for the decade prior, had been led by a good chief who established a platform of community policing. What was missing was a business plan.

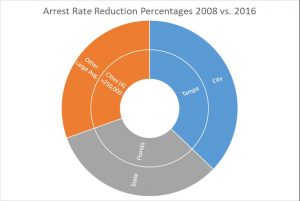

As of the 2016 reporting year to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, Tampa’s crime rate has been 16 percent lower than the Florida statewide average. While the journey to lowering crime significantly in all Tampa neighborhoods is a worthy story, the real power in the agency’s success is that its approach is both repeatable and sustainable—without necessarily requiring an increase in the number of officers.

The Journey

The Beginning

After self-benchmarking in early 2003, Tampa discovered that its crime rates were extremely high when compared to the statewide average and other large city averages both in and outside Florida. The first step in developing a solution to this challenge was a leadership re-write of the mission statement to make it actionable and functional. The Tampa Police Department was like many agencies—the former mission statement read like an eloquent greeting card. No one could remember it exactly, but it looked pretty in the multiple government-grade frames hanging in the hallways.

The new mission statement, in contrast, was simple and executable with three interlocking goals: (1) reduce crime, (2) improve quality of life, and (3) do numbers one and two through cooperative partnerships.2 Everyone knew this clear mission statement; no decisions were made without those three components being considered.

As the mission improved, so did the agency’s strategic vision. It did not take long to realize that moving into a CompStat model with a mission edict of reducing crime required leadership, management, and accountability. Several years into double-digit reductions, the data showed that four particular crimes—burglaries, auto burglaries, robberies, and grand theft autos—accounted for a significant proportion of the crime in the city. This understanding led to a strategic Focus on Four plan. With the four crimes in strategic focus came the need to give the three district commanders the tactical resources to meet the mission statement and strategic plan, which led the agency to utilize an intelligence-led policing approach.

The Middle

By 2008—about five and one-half years into the crime reduction journey—all the success came to a screeching halt in a single balmy August. What goes down (in this case, crime) will often go back up—or try to. Gaining, sustaining, and maintaining are yet additional business-problem challenges for law enforcement leadership to tackle in a CompStat model. An executive leadership professor once shared that whatever effort it took to gain 80 percent of your goal, it will require another 100 percent effort to achieve the remaining 20 percent.3

Prior to August 2008, Tampa had realized a 52 percent reduction in the overall crime rate. Great, right? But, considering that in 2002, the jurisdiction’s crime rate was 110 percent higher than the statewide average and pushing 30 percent higher than the crime rate average of the other large cities in the state, there was still work to do. The first phase had helped the agency meet the more easily reached goals; the remaining challenges in taking the agency from good to great were daunting.4

The Grid Approach

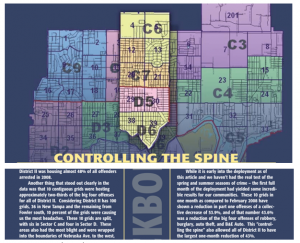

The City of Tampa, in round numbers, has 240 grids. Grids are the smallest geo-unit of measure and make up zones, which make up sectors, which make up the three current districts, each managed by one major who is supported by two patrol captains. For a 1,000-person agency serving a base population of over 350,000 with a constant influx of tourists, visitors, military families, sports fans, and college students, things can get busy very quickly.

Tampa’s grids were established in the 1970s, and the average size of a grid was approximately three-quarters of a square mile, and unless an irregular, natural border was in play, the grid was as square as possible based on the local road system in the city limits.

Describing the grid system has value, because it became the foundation for the red grid plan, which then offered crime reduction equity to all neighborhoods, one grid at a time. In 2008, when the dropping crime rate tried to reverse itself, 10 grids in the north eastern district were responsible for two-thirds of the district’s crime. So, in short, 10 percent of a 100-grid district was responsible for 67 percent of the crime and slowing down the city’s momentum.

Concept 1: Measure small, and keep small things small.

The 10 grids in question were grouped in a block of two grids across [East/West] and 5 grids long [North/South], and they straddled the center of the district by having 6 grids in the northern sector and 4 in the southern sector. Keeping the focus specifically on this small area allowed for a manageable, targeted approach.

Concept 2: Give a target area a non-neighborhood [theatre-type] nickname.

This helps with operational and support buy-in, but it’s important to ensure the name has no geo-political or geo-social or overly para-militaristic connotations that could unintentionally detract from the agency’s efforts by drawing negative attention from the media or the public. For example, the clearly delineated high-crime density area in Tampa was nicknamed the “Spine” because of its location and shape.

This helps with operational and support buy-in, but it’s important to ensure the name has no geo-political or geo-social or overly para-militaristic connotations that could unintentionally detract from the agency’s efforts by drawing negative attention from the media or the public. For example, the clearly delineated high-crime density area in Tampa was nicknamed the “Spine” because of its location and shape.

Concept 3: Use the W.I.N. approach.

Set priorities by considering “what’s important now” (W.I.N.) for all geospatial aspects of the jurisdiction.5 What is the biggest problem in the smallest manageable area? Focus on that specific issue without jeopardizing the overall mission and strategic focus of the agency and community.

For example, in Tampa, residential burglaries with a kick-in style modus operandi was the most common crime in the Spine. This was occurring during the Great Recession, and flat panel TV sets were being stolen—often by order—and sold on the street. There were no pawn shops involved or witnesses to question, just a bunch of people coming home after a hard day’s work in a lower socio-economic community to major property loss and associated damages.

The first thing that was apparent was that directed patrol did not work to prevent these crimes. Any type of patrol saturation plan should involve a conversation with a senior officer who can advise how many times he or she witnessed a major felony offense in progress. Typically, it’s very few over a career. Thus, in situations such as this, expending patrol units in a high-crime area might not bring the desired results. Arguably, there are many suitable targets (TVs and other electronics) in the area of responsibility and few offenders. Again, look and manage the smaller number (offenders) to help avoid the bigger numbers (crimes).

In the case of the Spine, the offenders turned out to be members of a street gang or neighborhood affiliation group of mostly juvenile offenders who were well-managed by a few adult members.

Concept 4: Know and manage your adult and juvenile offenders by type and area to the smallest categorization.

By raising the front-line experience quotient of known offenders, this concept can be quickly utilized in a process called sense-making, which is simply layering known answers on top of unknown problems to help resolve the ambiguous situation.

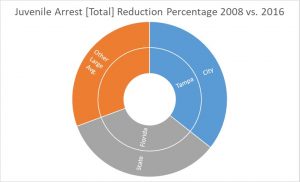

Managing offenders is not all about arrests; in fact, that should be the last resort. In the aforementioned years of crime reduction, many arrest avoidance and diversion tactics were used, lowering all arrests by 48 percent and juvenile arrests by 56 percent while still reducing crime by over half.

Instead of arrests, Tampa Police Department employed community policing tactics such as intersection roll calls and front porch roll calls. The intersection roll calls were designed to tell the troubled neighborhood that the “good” forces in the community were going to take back the neighborhood, one block at a time in the W.I.N. philosophy.

Front porch roll calls were designed to meet two objectives. The first was to allow the squads and community to have a sense of mutual appreciation for each other. The porch roll calls were designed to be held on the last day of the squad’s work cycle—so they could go home with a feeling of accomplishment and return several days later with focus and purpose by humanizing their engagements. The second objective was to listen and prevent. Those small interactions were a large part of the recipe to prevent crime and understand pre-arrest opportunities of engagement with anyone on the brink of offending or re-offending. The police might not know all that goes on in a small community 24/7, but the residents do. The agency’s goal was to have one neighborhood watch leader for each of the 240 grids in the city limits.

Concept 5: Enhance community resources.

As discussed, arrests and citations cannot be the sole prevailing tactic to reduce crime. In fact, like car pursuits, all arrest encounters should be considered a risk and the business model should be such to avoid those encounters as much as possible by design and policy without jeopardizing the mission or strategic plan outcomes.

The main community policing tactic employed by the Tampa Police Department was the enhancement of, and increase in, R.I.C.H. Houses. R.I.C.H. stands for Resources in Community Hope, and a R.I.C.H. House is simply a once-abandoned home or duplex converted into an after-school or out-of-school safe house for kids within a high-crime neighborhood. In fact, in 2008, when the crime rate was creeping back up, the officer assigned to the Spine’s R.I.C.H. House was being targeted to hit the street by the sector leadership. However, refined analysis showed the importance of her role as a community “feather” instead of having all “hammers.”

Concept 6: Crime reduction requires a “hammer” AND a “feather.”

If only one strategy—enforcement or community policing—is used, it quite often will not work as needed. Some agencies tend to shy away from preventative enforcement efforts and do only the community relations aspect for fear of over-policing a challenged neighborhood, unintentionally leaving the good people in high-crime areas to the wolves. Agencies cannot forget victims.

One tactic used by the Tampa Police Department to ensure victims were a priority was to pull crime victims’ photos during CompStat to help humanize the need for real results and have the commander share the intimate details of the offenses. Beginning officers and deputies raise their right hands and swear in as ready to save the world, but spend much of their time writing offense and car crash reports with the mantra of keeping the report simple and not getting emotionally involved. It is difficult to reverse that culture without a leadership and management disruption to those practices.

Concept 7: Seek out objectivity.

Since humans are subjective, they tend to subjectively share information and intelligence. In law enforcement, this does nothing except increase the risks to officer safety and potentially aid the offenders, who benefit from this antiquated style of communication. Intelligence-led policing achieves full value only if information (1) is provided in real time and not delayed; (2) has a synchronous feedback loop; and (3) has a sense-making capability. These three components help to de-randomize communication efforts and allow agencies to increase their offender intelligence while effectively managing their areas of responsibility.

It is this de-randomization of daily activities through a good intelligence-led process and supportive technology that allows officers, detectives, and analysts to become more precise and surgical in the strategic space of the agency. Using objective technologies to help script actionable priorities is key to trust building. This approach helped Tampa reduce adult and juvenile arrests far below the statewide averages. It is one thing to lower crime, but it is another thing to do it while exponentially lowering arrests. It’s important to note that technologies that support these efforts need to fulfill three qualifications to be effective: (1) be intuitive and inclusive, (2) makes information-to-intelligence highly actionable, and (3) encourages proactive policing vs. reactive policing. The technology needs to for “doing,” not “viewing.”

Concept 8: Officers tend to work better in teams.

If there is any doubt regarding this concept, observe officers on a special event deployment and note how they gravitate to each other as opposed to being spread out by assignment. So, why fight this inclination? In Tampa, what was originally 42 patrol zones were broken down into 31 zones covering three patrol districts each having two, 5-zone sectors, and one special zone that was a geographical space annexed years ago in the far northeast section of the city limits.

These slightly larger zones, balanced by calls for service, total crime rates, investigative time involved, offender density, and response times, allowed a 10-person squad to have two patrol units for each zone. Add a supervisor and an assistant supervisor for a total 12-person squad and the “sum being greater than the parts” approach increased the strategic momentum to the patrol sector. Most zones were technically manageable, and, during the annual strategic planning sessions, the commanders would get a zone breakdown of effort so when people are off or at training, they knew which of the five zones should keep the two patrol cars as a necessity.

Concept 9: Times to arrest affects crime rates.

During the plateau period of 2008, one thing that was measured by the Tampa Police Department was time to arrest. It became very apparent that the faster a case was closed by arrest, the greater the impact on crime reduction (by crime type). This led to an effort where squads of officers that were formerly street anti-crime and street-level narcotics units were merged into a street-level undercover layer that did high-speed follow-ups on the top four crimes that plagued the city. Having this unit to fill the gap between the patrol units and the detectives allowed cases to be solved much faster and, more importantly, established area accountability (zone) versus functional responsibility (drugs). This deployment of resources created a prioritization model that allowed the most important problem to be addressed in each neighborhood. While working high-crime areas and drug holes were important, the approach was too generic and did not offer the equitable outcomes of all neighborhoods benefitting from holistic crime reduction and quality-of-life improvements.

While many agencies might not have the capability or resources for this enhanced undercover personnel layer, a well-informed officer can be empowered to perform follow-ups by leveraging information sharing technologies.

Concept 10: Focus on areas instead of offenses.

As the agency began gaining momentum in the next phase of crime reduction, it became more important to de-specialize detectives and assign them to areas versus offenses. The only exceptions were detectives for homicide and sex crimes, where the intimacy of the victimization and witnesses and prosecution factors are elevated; otherwise, detectives worked all crimes in their specific zones. This aligned them with patrol and the newly created undercover street units, also assigned by geography, to work as a layered team. It proved fruitful, leading to community rapport and better crime prevention tactics.

As the patrol, undercover officers, and detectives’ knowledge grew area by area, the equitable dividends paid off for each neighborhood.

Sustainment

Once crime reduction, deployments, planning cycles, and community-policing tactics become normalized, how does an agency sustain these efforts over the next set of administrations? The answer lies in technology.

One big lesson learned by the Tampa Police Department was that the police department’s culture was less predictable than the crime and offenders. Anything from shift change, promotions, retirements, shift bidding, new assignments, days off, vacations, or leave of absences can work to the offenders’ advantage. These changes are healthy and normal for an agency, but technology can remove the subjective nature of what these activities do when it comes to collecting and sharing information and intelligence about a neighborhood, which is exactly what community policing is designed to accomplish. The more the police know and understand about a neighborhood and crime, the more crime they can prevent—and the more crime the police can prevent, the more the community, as a whole, can thrive.

Technology used to support equitable outcomes needs (1) to be intuitive and used by the agency’s critical mass; (2) to be usable in real-time; (3) to have a feedback loop that is also in true, real-time; and (4) to have a sense-making capability that makes the tool actionable to allow the augmentation of the agency’s collective whole of experience to solve problems quickly.

Conclusion

Crime will always morph and try to come back. However, if an agency has a solid and attrition-proof business intelligence system in place, it will not only prevent such a rise, but it will bring about gains in officer safety and community trust. After all, it’s never about “us” and “them”—it’s only about the community as a whole.

After developing an actionable and sustainable mission, vision, and value statement, coupled with a solid strategic plan that achieves equitable outcomes, the utilization of intelligence-led processes supported by the right technology can lead to objective, equitable change in crime rates. Overcoming years of silo-driven information and intelligence can be as simple as allowing function to follow form. Implementation of a speed-meets-distribution and feedback model allows for the sense-making process of keeping small problems small and reducing crime everywhere.

Notes:

1FDLE UCR Crime Report, County and Municipal Defense Data, 2002.

2City of Tampa Police, Mission Statement, 2018.

3 Mendoza College, “Dr. Monica Sharma Receives Awards,” Mendoza College of Business: Ideas and News, November 17, 20009.

4 Jim Collins, Good to Great (New York, NY: Harper Business, October 2001).

5Brian Willis, “Want to W.I.N.? Decide ‘What’s Important Now,’” PoliceOne, June 2007.