Photo courtesy of Richmond Police Department, VA.

While the number of women in the field of policing drastically increased from about the 1980s to 1990s, growth has stalled in the last couple of decades.1

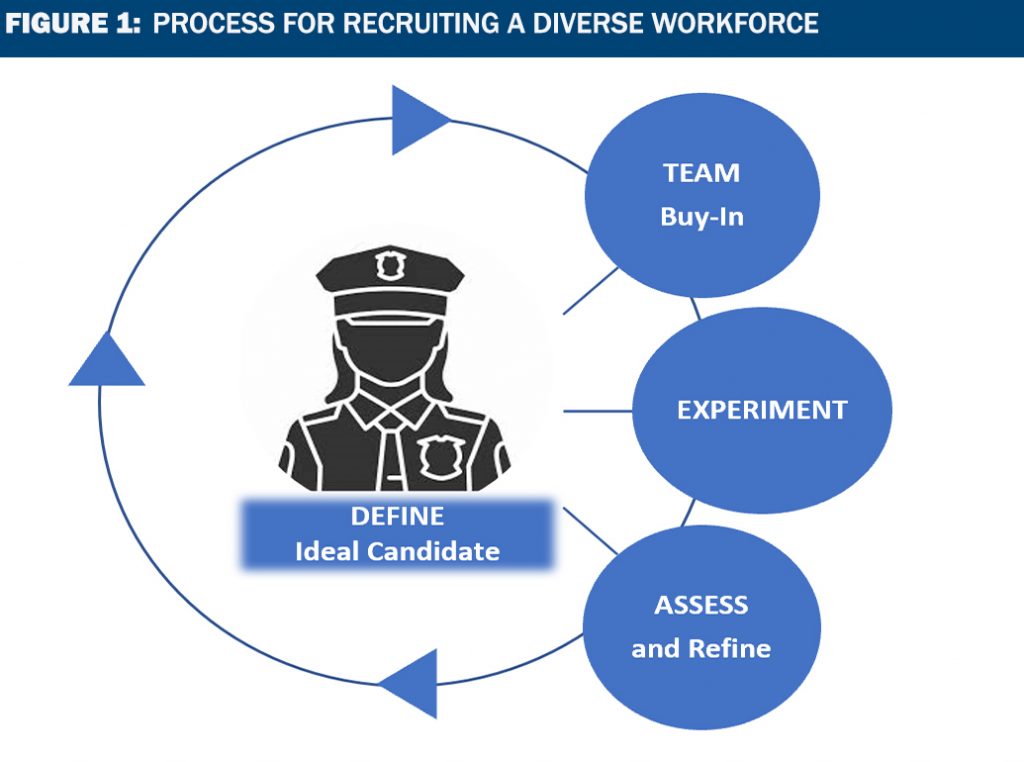

Women currently represent only about 12.5 percent of sworn U.S. officers, and recruiting a diverse workforce continues to be a challenge for many departments.2 Therefore, it is no surprise that there have been many recent calls to action, including from the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, the National Institute of Justice, and the International Association of Chiefs of Police. It is no secret that women add important benefits to the field and promote organizational change, a fact recognized by many policing professionals and agencies.3 When it comes to attracting diverse candidates, agencies may struggle with knowing where to start; however, there are four steps they can take to set them on the right path.

1. DEFINE Your Ideal Candidate

The first step in achieving anything is to establish a goal or set an intention. This is a critical step, and it’s important that the right intention is set. It may be tempting to start with a goal of “get more women to apply,” which leads to questions like “What do women want?” or “What will make women apply?” These questions are important, but the narrow focus may lead to strategies based on misguided assumptions or stereotypes. For example, it is common to assume that women are concerned with “family matters” or other “women’s issues,” so the marketing strategy includes pictures of women in uniform holding their kids. This practice may be a good strategy because many women do intend to have families and care about maternity and childcare options and these images are important; however, the strategy is guided by assumptions that all women—and only women—care about such issues. When used in isolation, such strategies ignore other aspects of policing that might attract women.

Agencies should consider starting, instead, with a broader focus fitted to policing: “What are the most desired skills and traits of a 21st-century law enforcement professional?” or “What type of person do we want patrolling the streets?” Communication skills, integrity, trust-building capabilities, and a capacity for a guardian mind-set, among other characteristics, may come to mind. These are the characteristics to keep front of mind when designing a recruitment process that works for everyone and is inclusive of and likely to attract women. Starting with the desired characteristics of a good police officer will help guide recruitment strategies that are designed to find women (and men) with these skills and can also help potential candidates see themselves in the position (i.e., they see a match between their skills and abilities and those needed for the job).

One frequently suggested strategy for targeting potential women candidates is to seek out applicants at gyms or athletic events because the assumption is that one will find physically fit women at these events. This approach may be successful to some extent, but it again comes from a very narrow focus, with a specific type of applicant in mind. That is, this strategy emphasizes traditional images of policing (e.g., physical strength) and looks to find women who can align with those images; it also ignores other characteristics that are important to 21st century policing, like strong communication skills. Instead of focusing on physical attributes, it may be more important to prioritize other important characteristics. For example, a police captain interviewed by the authors said that she would often hand her business card out to waitresses who exhibited great customer service skills and could handle difficult customers with ease. Her thinking was that these women already have a knack for dealing with people and they can easily be taught the physical maneuvers and tactics they would need on the job. Recruiting at gyms or sporting events may still be a beneficial recruitment strategy, but agencies should think more broadly about how and where they might find women who are likely to have the desired characteristics (and not just the physical ones). Once an agency has defined what it is looking for in candidates, everything else in the recruitment, application, selection, and training process should reflect that definition. This process should attract women with the desired skills while also minimizing barriers or obstacles.

2. Build Your TEAM, Promote Buy-In

Recruitment and hiring should be a year-round, ongoing process carried out by a team. The team may include any number of people, such as recruiters, public information officers, background investigators, academy instructors, psychologists, polygraphers, recruitment committee members, community partners, and officers out on the streets and in the schools. Once the team is identified, the members must be prepped for the task at hand. A critical piece of team preparation is making sure that they buy in to the agency’s recruitment goals. Specifically, if an agency is looking to recruit a workforce with 21st-century policing skills, the team must understand why bringing in people with diverse backgrounds and different characteristics is important and beneficial.

People who are enthusiastic about hiring the candidates with the qualities identified by the agency will be more effective recruiters. At the same time, a recent report by the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) recommends that leaders watch out for “culture guardians” within the recruiting team who are likely to protect more traditional images and exclude candidates they don’t see as fitting with those images (e.g., “lacks command presence”).4 Similarly, team members should be trained on implicit biases and how to recognize and watch out for them in the recruitment and selection process. Even those who are enthusiastic about the broader goals of diversity can be impacted by unconscious biases and can unintentionally impede progress toward recruitment goals.

Recruiting starts long before the job is posted. With women, in particular, the groundwork must be laid for them to even see policing as a career option. Interactions with officers that happen on the street or in the classroom can be an important part of laying that groundwork. For example, in a recent policing career presentation at a local university, a male officer told a room full of criminal justice students, many of whom were women, that he would not want his daughters to go into the field. He likely had good intentions; however, he sent a message to a room full of potential recruits that policing is not a great job for women. This example is not intended as a criticism of the officer, but rather it is an illustration of how important your team is in communicating the picture of your ideal candidate. The example also indicates the importance of getting the entire team on board. If the importance of diversity and, specifically, the recruitment messages are not embraced by all team members, then recruitment strategies will not be as effective.

3. EXPERIMENT and Think Creatively

The recognition that law enforcement needs to diversify its ranks is not new; however, there is still a lack of solid research on effective recruitment of women, and men, for that matter, to policing. The lack of systemic research on what works is frustrating because it means recommendations are just that, with little promise that they will work. On the flipside, due to the lack of research-based recommendations, agencies can be open to creatively experiment and even contribute to the evidence base on what works (and what doesn’t). There are many places to look for creative solutions and ideas.

Look to the Research

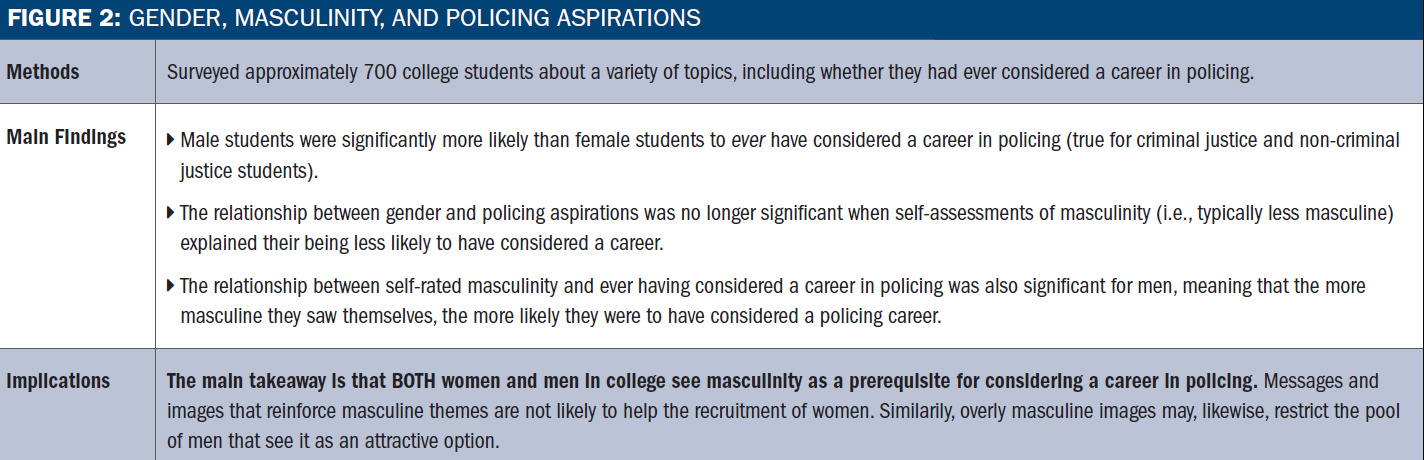

As stated, there is little research that specifically examines the success rates of various recruitment strategies. However, there is plenty of tangential research that can inform what might work or mistakes to avoid. Included here are a couple of examples from the authors’ recent research to illustrate, but there are also others out there that may help (e.g., research on barriers or obstacles).5 Results from Study 1 indicate that masculinity is an important predictor of even considering a career in policing, for both men and women (see Figure 2). Thus, recruitment strategies that promote traditional masculine images of policing could not only deter women, but also restrict the eligible pool of men.

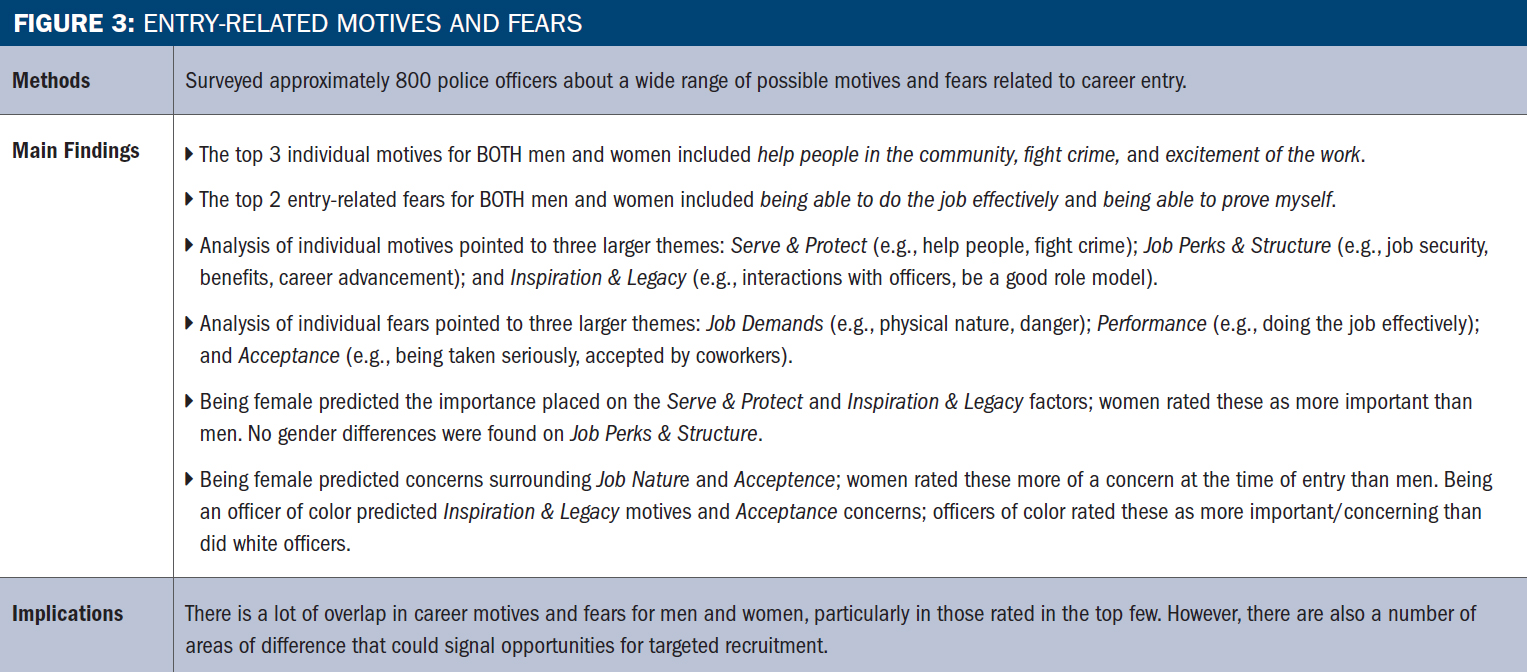

Results from Study 2 (see Figure 3) suggest that there are similarities between men and women with regard to their motives for joining law enforcement (e.g., helping people, fighting crime, and excitement). The good news is that these features of the job are likely well-known and highlighting them does not require much of a change in strategy. Most people, without being told, probably already associate policing with excitement and crime fighting, thanks to media representations.

Where the opportunity arises, however, is in the differences discovered. Although both men and women prioritized service, women rated it as more important than men did. Further, women and officers of color suggested that interactions with police, educational experiences, and the opportunities to be role models for others like them (inspiration and legacy) contributed to their motivation to enter the profession. Thus, agencies may consider prioritizing in-person interactions, potentially in educational settings, to connect with female candidates and candidates of color. Women and officers of color also noted concerns about being accepted and taken seriously. These concerns point to potential barriers that need to be combated in the recruitment process and may also signal areas for continued improvements for those already working in the field. Prioritizing in-person recruitment opportunities could also provide a space for candidates to discuss their concerns and learn how others in the field have managed similar concerns. Availability of mentoring, women’s policing associations, and other similar options can reinforce the message that candidates will be supported and included.

Adopt Ideas from Others

In addition to drawing recommendations from research, agencies can find models that have been successful in attracting diverse candidates and ask those agencies or organizations what is working for them. Look to recommendations proposed by policing-related organizations and publications. For example, the Police Executive Research Forum recently published findings on the police recruiting crisis, highlighting a number of innovative strategies that are being used by agencies around the United States.6 Nearly two decades ago, the National Center for Women and Policing put out a guide for recruiting and retaining women that included several strategies and suggestions that remain relevant today.7 When searching for ideas, it is important to keep in mind that just because something worked for one agency, doesn’t mean that it will work in another state, city, or agency. There is still a need for more research on the outcomes of recruitment strategies.

4. ASSESS, Adjust, and Refine

An important part of experimenting with innovative ideas is building in a feedback loop to help identify the extent to which the “experiments” are working. After defining what they are looking for in their candidates and trying new approaches to attract those candidates, it is time to gather evidence on the extent to which those approaches contributed to the agency’s goals and use that knowledge to inform and improve upon overall recruitment approaches.

The type of evidence gathered may depend on what is available and feasible, given agency capacity. It could be as simple as asking academy recruits what brought them to the field and which pieces of the recruitment and selection process were most influential or helpful. It could mean calling candidates that started the hiring process but did not continue and discovering what the obstacles were that stopped them. It might mean tapping into social media or other marketing analytics to determine which materials or campaigns get the best reception, or it could involve formal research in which strategies are randomly assigned and compared. Ideally, the evidence involves a mix of several of these measures.

As mentioned, an agency’s team is critical to the recruiting process. Persons focused on assessment are an important part of that team. Internal partners or team members may include officers or civilian personnel who have an enthusiasm for numbers and assessment. External partnerships also have value and could take many forms. There may be formal partnerships in which local researchers are paid to provide assessment and evaluation services, or there may be initiatives in which an agency partners with local universities to pursue federal, state, or foundation funds to support and evaluate a planned recruitment or retention initiative. There may also be informal opportunities for partnership. For example, university researchers might agree to provide analysis and input in exchange for the opportunity to publish scientific findings. Graduate students working on their theses or dissertation projects may also be resources for collaboration.

Concluding Thoughts

IACP Resources■ Women’s Leadership Institute ■ “Recruiting Women” (article) ■ “Transforming Law Enforcement by Changing the Face of Policing” (article) |

As agencies design or adjust their recruitment procedures, they need to keep in mind that the process is dynamic and each component is interrelated. Further, “recruitment” continues beyond soliciting applicants. Messages about who belongs and which characteristics and skills are desirable are communicated throughout the selection, training, and early socialization processes. As agencies try new approaches, the assessment piece is critical for measuring success and identifying opportunities for improvement. Having a good recruitment team and campaign can serve to attract quality candidates with diverse backgrounds and experiences; it may also have positive side effects for community attitudes and relationships. A recruitment process in which concepts like service, communication, and diversity take center stage sends a message to the broader community about the priorities of a 21st century police force. Further, when team members engage potential recruits, even those who decide not to apply may walk away with a more positive image of the police in their community.

Notes:

1 Anne L. Kringen, “Scholarship on Women and Policing: Trends and Policy Implications,” Feminist Criminology 9, no. 4 (September 2014): 367–381.

2 United States Department of Justice, Crime in the United States, 2017, table 74, Full-Time Law Enforcement Employees by Population Group: Percent Male and Female, 2017 (2018).

3 Amie M. Schuck, “Female Representation in Law Enforcement: The Influence of Screening, Unions, Incentives, Community Policing, CALEA, and Size,” Police Quarterly 17, no.1 (2014): 54–78.

4 Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), The Workforce Crisis and What Agencies Are Doing About It (Washington, DC: PERF, 2019).

5 Natalie Todak, “The Decision to Become a Police Officer in a Legitimacy Crisis,” Women & Criminal Justice 27, no. 4 (2017): 250–270.

6 PERF, The Workforce Crisis and What Agencies Are Doing About It.

7 Penny E. Harrington et al., Recruiting and Retaining Women: A Self Assessment Guide for Law Enforcement (Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Women & Policing, 2000).

Please cite as

Samantha S. Clinkinbeard and Rachael M. Rief, “Four Steps to Bring More Women into Policing: Define, Build, Experiment, and Refine,” Police Chief 87, no. 4 (April 2020): 40–45.