In the United States, suicide rates have been rising over the past several years. More officers die by suicide than in the line of duty.1 But, law enforcement leaders have the power to make change by applying key strategies to prevent suicide. Research in suicide prevention has led to the identification of successful interventions and programs. Law enforcement leaders can make significant contributions to the prevention of suicide in their ranks through implementation of evidence-based programming and leading by example to demonstrate that all people face challenges when experiencing trauma, stress, and other difficulties—and that support is available.

A comprehensive suicide prevention program requires a holistic approach addressing the many pieces that play roles in this complex issue. Preventing law enforcement suicide requires an all-in effort from families, communities, peers, leadership, mental health and health professionals, and paraprofessionals. A strategic suicide prevention plan for a law enforcement agency should include the following objectives:

■ Creating and sustaining a leadership culture that destigmatizes mental health

■ Increasing and normalizing help-seeking behaviors

■ Preparing for and providing support during transitions (time off due to injury, retirement, etc.)

■ Addressing and reducing the impact of trauma including cumulative stress

■ Developing and strengthening peer supports

■ Identifying and responding to signs of suicide risk, including intimate partner violence and substance misuse

■ Improving access and decreasing barriers to mental health care

■ Reinforcing resilience and healthy coping skills

■ Promoting a positive, resilient message

■ Supporting law enforcement members and families impacted by a suicide loss or attempt

As part of this comprehensive approach, there are several key strategies that peers, leaders, and family members, as well as other support people, can do to reduce risk and increase protections against suicide. These include strengthening connectedness, recognizing warning signs of risk, augmenting safety planning, and communicating a positive and resilient narrative through intentional messaging.

The Power of Connectedness

Suicide prevention involves more than pulling a person out of an emotional fire. Suicide prevention requires going upstream, prior to any crisis, to reduce the factors that might contribute to suicidal thinking and behaviors. Belongingness and connectedness are some of the strongest protections against suicidal thinking. It is known that law enforcement members often don’t share with family members what they experience on the job. Law enforcement agencies need to intentionally support the processing of trauma, build officers’ connections within the department and outside of work, and recognize signs of isolation and relationship problems.

Research with people who have attempted suicide and refused follow-up treatment shows simple actions can make a big difference.2 In a random control trial that has been replicated several times, simply sending a postcard over a period of time with a non-demanding, caring message helped people live.3 Those who received the postcards were less likely to die by suicide than the group that did not receive these messages.4 These caring contacts didn’t ask for anything and didn’t tell the person to go to therapy, take their medicine, get enough sleep, or refrain from drugs or alcohol. The messages merely expressed that the person was thought of and someone cared about them. Law enforcement leaders, peer supporters, and law enforcement members can provide messages like this, too.

A Culture and System of Support

Support matters for the officer thinking about suicide. Support matters for the officer struggling with life’s challenges who is not in a suicidal crisis. Support matters for the officer dealing with substance misuse issues, relationship problems, financial problems, and the cumulative stress of the job. Support matters for the officer coping with trauma and vicarious trauma. Support comes in many different forms, and it can be built into the organization through policies, procedures, and resources. Allowing for and encouraging the use of employee assistance programs, mental health treatment, and debriefing personally traumatic events are some examples of how support can be built into policies and procedures. Policies will often provide standard supports for officers who fired their weapons, but the other officers involved in the scenario may also need support. It’s important to remember that different people react differently to the same events and experiences. For instance, witnessing a dead child may be particularly traumatic for one person, while seeing a person who has been severely sexually assaulted may be more challenging for another. Policies can also support mental health days, flexibility in scheduling to allow for meeting the needs of personal life, and mental health check-ins on a regular basis.

Peers can help to increase social connectedness, send caring messages, decrease the stigma of getting help, and reinforce positive coping strategies.

Support can be infused into the work culture and each team in the agency. It can be taught through training and education about mental health issues, the signs of suicide in law enforcement and how to respond to these signs, and coping with trauma and building resiliency. Formal supports can include peer support; accessible mental health checks and treatment, both internal and external to the department; and leadership check-ins.

Importance of Preparing Peers, Family, and Leaders to Offer Support

There are many ways peers can make a big impact on suicide prevention. Peers can help to increase social connectedness, send caring messages, decrease the stigma of getting help, and reinforce positive coping strategies. Peers should be trained to identify warning signs of suicide risk, ask directly whether a fellow officer is thinking about suicide, know what to do when a suicide risk is identified, and implement strategies to follow up with the officer at risk. Peers can use their experiences and knowledge to engage a person thinking about suicide and to ask about suicide in a way that might elicit a true response. Command staff should discuss the process and relevant policies their agency has regarding the safe, supportive, and effective reporting of officers who express active suicidal thoughts or desires. Peer supporters, officers, and command staff alike can be trained in using an evidence-based resource to ask directly about suicide, such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, Screener version.5 Peers should be trained to know the best practices in suicide prevention, such as increasing protective factors against suicide; decreasing risk factors; using a safety plan; having conversations about access to lethal means; and providing caring, supportive follow-up.

|

Six Questions That Could Save a Life In the past month, 1. Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up? 2. Have you actually had any thoughts about killing yourself? Yes – Go to question 3 3. Have you thought about how you might do this? 4. Have you had any intention of acting on these thoughts of killing yourself, as opposed to you have the thoughts, but you definitely would not act on them? 5. Have you started to work out or worked out the details of how to kill yourself? Do you intend to carry out this plan? In your lifetime or in the past three months, 6. Have you done anything, started to do anything, or prepared to do anything to end your life? Any “Yes” indicates that someone should seek a behavioral health referral. If the answer to 4, 5, or 6 is “Yes,” seek immediate help—and stay with the person until they can be evaluated. For more information and resources, visit the Columbia Lighthouse Project. |

Many supporters in an officer’s life might have an idea of indicators that a person could be at risk for suicide or struggling emotionally. Talking about suicide, expressing a desire to die, stating that life isn’t worth living or has no purpose, and communicating that one is a burden to others are significant signs of suicide risk. In addition to these signs, increasing substance use, withdrawing, isolating, expressing hopelessness, feeling trapped, acting recklessly, and demonstrating mood changes are also important warning signs.6 In law enforcement, it is also key for supporters to look for life stressors and violent behaviors. Life stressors include relationship, financial, legal, and work problems. If an individual is facing challenges in several of these areas, it may prevent a further crisis to provide support, mental health treatment, and follow-up before a crisis emerges. Similar to the evidence that current violent behaviors are a sign of future violent behaviors, suicidal behaviors are also a form of violence. If a law enforcement member has demonstrated violent behaviors in intimate relationships, outside of work, or in his or her role as a police officer, this should be seen as a sign of that officer’s own suicide risk and needs to be taken seriously.

Those who support law enforcement, such as family, frontline supervisors, and peers, need to be prepared. While law enforcement officers may feel ready to respond to an external person in a suicidal crisis, they may be less prepared to ask people within their own ranks if they are thinking about suicide. All members of law enforcement should be trained to ask openly and directly about suicide in a way that builds trust with the person who may be in crisis. It is best to use the language of the person at risk, meet him or her where the person is at, and to rely on the relationship that supports a difficult conversation. In addition to this, it is useful to know an evidence-based tool that can help elicit suicidal thinking and behaviors. Six questions can be memorized and added to the repertoire of law enforcement to identify suicide risk using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (see sidebar).7 While this scale is a great tool, it is imperative for those supporting a person in crisis to communicate in a way that is culturally sensitive and connects on an individual basis.

Safety Planning for Suicide Prevention

One evidence-based approach to reduce suicide is using a safety plan to identify ways to support someone in a suicidal crisis. The safety plan is a customized plan developed collaboratively with a person at risk for suicide. It is used to teach a person at risk for suicide to identify what signs indicate things are getting worse, ways to tolerate distress other than suicidal thinking and behaviors, and who to turn to for support. The safety planning intervention was developed by Barbara Stanley, PhD, and Greg Brown, PhD, and is an evidence-based brief intervention for a person at risk for suicide. Research has shown the efficacy of safety planning in military and veteran populations.8 A similar tool, which is also evidence based and has been researched in military and veteran settings, is the Crisis Response Plan developed by Craig Bryan, PsyD, ABPP.9 Both of these tools include a prioritized list of coping strategies and supports that can be accessed easily and quickly during or before a suicidal crisis. Mental health professionals working with law enforcement should be trained in and knowledgeable about the use of a safety planning intervention. The mental health treatment professional can develop a safety plan with a person thinking about suicide, and peer support can reinforce the use of this safety plan. Peer support specialists, supervisors, and family members must also know about the use of safety planning and the role each of them can play in augmenting an individual’s safety plan.

The following are six elements of a safety plan.

■ Identifying one’s personal warning signs of a crisis or that a crisis may be impending

■ Outlining internal coping strategies that help specifically during a suicidal crisis

■ Planning places and support people who may assist in providing some safety and distraction

■ Identifying at least three go-to persons who will provide necessary support during a suicidal crisis

■ Detailing mental health crisis resources

■ Taking action to make the environment safe for the person at risk10

Establishing environmental safety includes safe storage of firearms, medications, and other potentially lethal items or substances. For law enforcement personnel, a safe environment can include using an image that represents a protective factor, such as a personally meaningful picture of something or someone that keeps the person going (family, spouse/partner, pet, spiritual image, etc.), with the storage of the firearm. A vinyl wrap, such as those created by Cover Me Veterans, that has a customized image of something that matters the most to the person at risk may provide some protection against suicide with that specific method.

Communicating Safely to Promote Life and Hope

|

TAKE ACTION NOW TO LEARN MORE. How to ask about suicide Safety planning Veterans Administration Safety Plan Quick Guide Safe messaging |

In addition to supports on an individual and organizational level, the overarching conversation about law enforcement suicide prevention must be focused on a positive, resilient, and hopeful message. It is essential to honor those lives that have been lost and, at the same time, respect those who are struggling. Caution must be exercised when talking about suicide in agency communications and media and community settings, and the agency culture must be considered. It is key to communicate to law enforcement members that there is hope, suicide is not inevitable, and there is no need to struggle alone. Empowering leadership and peers to share their stories of mental health challenges, coping through trauma, substance use issues, getting help with intimate partner violence, and resilience through a suicidal crisis will have a profound impact.

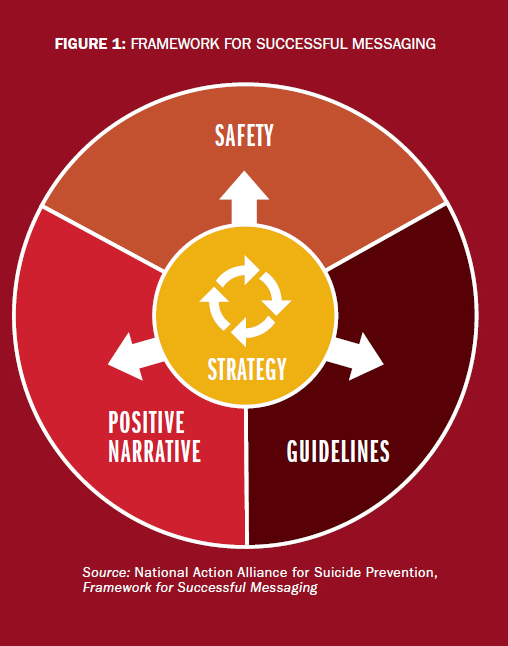

Administered by the Education Development Center, the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, the public-private partnership dedicated to advancing the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, has developed a Framework for Successful Messaging. The framework was designed to assist people in the development of strategic, safe, and positive messages about suicide prevention.11 Any communication put out by a department or other organization about law enforcement suicide—including prevention—must be crafted with a safety lens.

The overarching conversation about law enforcement suicide prevention must be focused on a positive, resilient, and hopeful message.

Safe messaging focuses on avoiding potentially harmful messaging content while advancing a suicide prevention strategy. Certain messages about suicide can increase the likelihood that a person at risk for suicide may be more likely to think about or attempt suicide themselves. Communication about suicide should avoid sensational coverage, details about suicide methods or locations, expressions that suicide is common, overemphasis of suicide death data, and portrayals of a simple explanation for suicide.12 Agencies can advance safe messaging by connecting the communication about suicide to a comprehensive prevention strategy, stating that the issue of suicide is complex, sharing stories of resiliency and hope, and advancing a positive narrative. It is essential to highlight solutions to stigma rather than the problem of stigma. Law enforcement officers are solution oriented; clear messages that communicate positive, simple, and direct actions will help empower them to do something about this problem in their own ranks.

The messages communicated by chiefs and command staff within an agency help to determine the culture of the organization. It is essential that any poster, internal communication, and information distributed at roll call and meetings be created with intention. Yet, it is even more imperative that the agency’s action communicates a culture of comradery, connection, inclusion, support, and resiliency. Law enforcement members have incredibly difficult roles and wear many hats. Officers may need a space to transition from the role of officer to the role of parent, spouse, sibling, and friend. As the saying goes, actions speak louder than words. Actions plus intentional words to create an agency that truly does have the mental well-being of its members as a priority speaks even louder.

Conclusion

Together, the law enforcement community has the power to prevent suicide, and leaders must make this a priority. All those who support law enforcement must strengthen the safety net. The National Officer Safety Initiative’s National Consortium on Preventing Law Enforcement Suicide will provide recommendations and develop a resource toolkit to assist agencies in developing a comprehensive approach to this difficult problem. Without hesitation, reach out to someone who you know is going through a hard time, address your own self-care, and make changes to support all law enforcement members. d

Notes:

1 Jena Hilliard, “New Study Shows Police at Highest Risk for Suicide of Any Profession,” Addiction Center, September 14, 2019.

2 Jason Cherkis, “The Best Way to Save People from Suicide,” Huffington Post, November 15, 2018.

3 Gregory L. Carter et al., “Postcards from the Edge Project: Randomised Controlled Trial of an Intervention Using Postcards to Reduce Repetition of Hospital Treated Deliberate Self Poisoning,” BMJ 331 (2005); David D. Luxton et al., “Caring Letters for Suicide Prevention: Implementation of a Multi-Site Randomized Clinical Trial in the U.S. Military and Veteran Affairs Healthcare Systems,” Contemporary Clinical Trials 37, no. 2 (January 2014): 252–260; David D. Luxton, Jennifer D. June, and Katherine Anne Comtois, “Can Postdischarge Follow-Up Contacts Prevent Suicide and Suicidal Behavior? A Review of the Evidence,” Crisis 34, no. 1 (January 2013): 32–41; Jeremy A. Motto and Alan G. Bostrom, “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Postcrisis Suicide Prevention,” Psychiatric Services 52, no. 6 (June 2001): 828–833.

4 Motto and Bostrom, “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Postcrisis Suicide Prevention.”

5 Kelly Posner et al., “The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings from Three Multisite Studies with Adolescents and Adults,” American Journal of Psychiatry 168, no. 12 (December 2011): 1266–1277.

6 Suicide Prevention Resource Center, “Warning Signs for Suicide.”

7 The Columbia Lighthouse Project, “First Responders.”

8 Barbara Stanley and Gregory K. Brown, “Safety Planning Intervention: A Brief Intervention to Mitigate Suicide Risk,” Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 19, no. 2 (May 2012): 256–264; Megan S. Chesin et al., “Staff Views of an Emergency Department Intervention Using Safety Planning and Structured Follow-Up with Suicidal Veterans,” Archives of Suicide Research 21, no. 1 (January 2017): 127–137.

9 Craig J. Bryan et al., “Effect of Crisis Response Planning vs. Contracts for Safety on Suicide Risk in U.S. Army Soldiers: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” Journal of Affective Disorders 212 (April 2017): 64–72; Craig J. Bryan et al., “Effect of Crisis Response Planning on Patient Mood and Clinician Decision Making: A Clinical Trail with Suicidal U.S. Soldiers,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 1 (January 2018): 108–111.

10 Stanley and Brown, “Safety Planning Intervention”; Chesin et al., “Staff Views of an Emergency Department Intervention Using Safety Planning and Structured Follow-Up with Suicidal Veterans.”

11 National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Public Awareness and Education Task Force, Framework for Successful Messaging (Washington, DC: Education Development Center, 2014).

12 National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Public Awareness and Education Task Force, Framework for Successful Messaging.

Please cite as

Jennifer Myers, “Key Strategies to Prevent Suicide Among Law Enforcement,” Police Chief 87, no. 5 (May 2020): 26–31.