Everyone has seen it. Drivers on the roadways are consistently talking on cellphones, manipulating handheld devices, eating, reading, and conducting many other activities while driving. The results are devastating:

- On U.S. roadways in 2017, 3,166 people were killed in 2,935 fatal crashes involving driver distraction. That same year, there were 401 fatal crashes reported involving cellphone use as a distraction.1

- Six percent of all drivers involved in fatal crashes were reported to be distracted at the time of the crash.2

- Nine percent of drivers 15 to 19 years old involved in fatal crashes were reported to be distracted.3

- Distracted drivers are about 4 times as likely to be involved in crashes as those who are solely focused on driving.4

- Drivers who are texting can be over 20 times more likely to crash than non-distracted drivers.5

The statistics are sobering, especially considering that the proliferation of handheld devices, particularly cellphones, continues to increase. Across the world, there are more than 600 million passenger vehicles; in contrast, there are more than 4.6 billion cell subscriptions.6 In a large sample of U.S. drivers, nearly 60 percent admitted to engaging in at least one cellphone-related distraction while driving in the past 30 days.7 The temptation to use these devices while driving is difficult to overcome.

Driver distraction is a broad problem, and many things can cause it. In order to assess the problem and develop countermeasures, the definition is important. There are three types of driver distractions:

- Visual—taking one’s eyes off the road

- Manual—taking one’s hands off the wheel

- Cognitive—taking one’s mind off the task at hand (driving)8

Any activity that causes one or more of these conditions is considered a distraction. Activities that create two or more of these distraction types are especially dangerous.

Traffic safety must be a primary focus of law enforcement. Across the United States, far more people are killed in traffic crashes than in homicides.9 Also, 90 percent of crashes are caused by driver behavior.10 By working to improve driver behavior and encouraging voluntary compliance with the law, law enforcement can contribute to significant safety improvements on the roadways. Addressing driver distraction is an important part of this responsibility.

What Is Known About Driver Distractions

A Virginia Tech Transportation Institute (VTTI) large-scale, crash-only analysis of naturalistic driving data showed that many activities secondary to the task of driving increase the risk of a crash.11 The analysis used a database of information gathered from more than 3,500 drivers across a three-year period. The naturalistic driving data were collected automatically from every trip taken in volunteer participants’ vehicles using a VTTI-developed data acquisition system. Video cameras, accelerometers, GPS, forward radar, and other technologies captured the data. The results definitively indicated that distracted driving is “epidemic,” with handheld electronic devices having high use rates and high risk.12

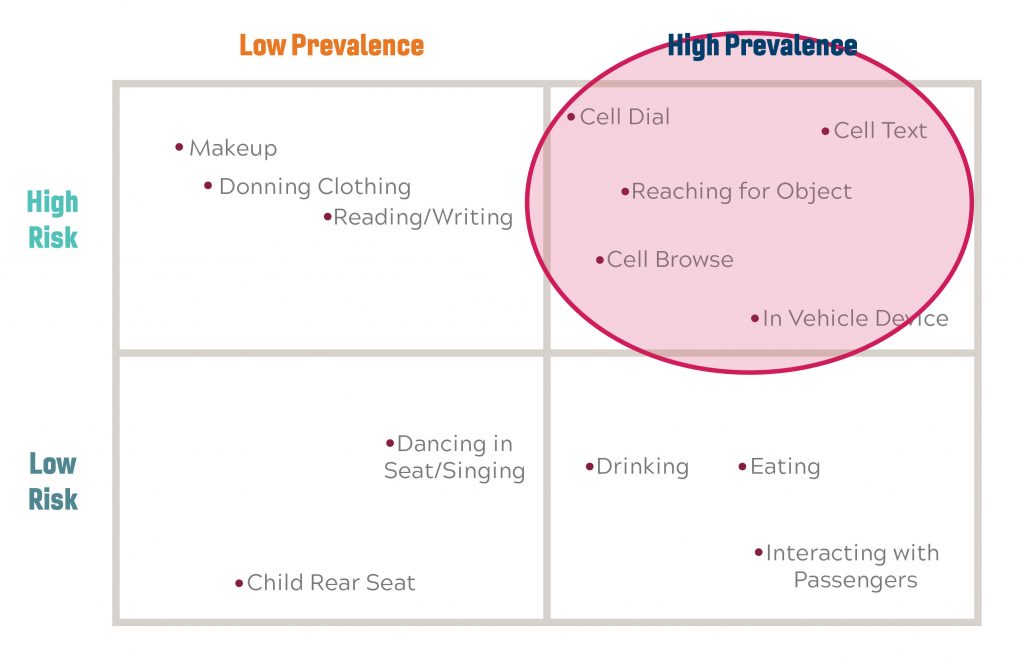

The VTTI analysis further showed that some secondary activities are low prevalence (like applying eye makeup) and others are high prevalence (like texting). Those same activities were evaluated by risk level. The results may be represented on a graph of four quadrants: low risk/low prevalence; high risk/low prevalence; low risk/high prevalence; and high risk/high prevalence.13

The graphed results in Figure 1 clearly illustrate that secondary activities that are low risk/low prevalence (like singing) raise the likelihood of a crash only slightly, while high risk/high prevalence activities (like texting) significantly increase the likelihood of a crash.

Another important finding of this research is that having a conversation on a hands-free device seemingly does not increase the overall crash risk. While there is some discussion among this particular level of distraction, it is still promoted by the National Safety Council that hands-free devices do not eliminate cognitive distractions.14 This is important for both public education as well as internal policy-making considerations.

Law Enforcement Countermeasures

Educate the Public: There are many driver distractions. The most effective and efficient manner of reducing distraction-related crashes is to focus on the riskiest and most prevalent secondary activity— handheld phone use.

Smartphones are a significant part of daily life for many people. They serve as personal assistants, cameras, and communications links to family, friends, and work. Smartphone users are accustomed to having instant access to text messaging, email, social media, and the internet. Disconnecting from the device to focus on the driving task is difficult for many drivers.

Enforceable legislation limiting the use of handheld communication devices while driving is essential to the safety of road users. As of March 2020, 21 U.S. states had passed laws that prohibit drivers from holding a communication device while driving. For example, the Virginia General Assembly recently passed legislation that will make driving while holding a handheld electronic device illegal in the commonwealth.15 The new law has a delayed effective date, allowing a period for educating the public regarding the provisions of the law.

Laws banning the use of handheld personal communication devices while driving should consider being primary and unambiguous. Virginia’s previous distracted driving law prohibited texting or emailing while driving, but allowed drivers to check social media, take selfies, watch videos, and engage in other activities on handheld devices. These exceptions made the law unenforceable. The new law removes ambiguity—if someone is driving with the device in hand, her or she is violating the law.

Efforts to reduce distraction-related crashes will require an education component to be successful—a shift in the “social norm” is needed. Alcohol-related traffic crashes have declined steadily over the past few decades largely due to education campaigns advising motorists that driving under the influence is socially unacceptable and that they can be arrested for driving while impaired. The same shift in attitude is required to address the distracted driving epidemic.

Police agencies have unique opportunities to influence driver behavior:

- Encourage young drivers to speak up when they see a friend driving while distracted. In a large study, younger drivers reported higher levels of cellphone-related distraction than older drivers.16 High school resource officers can educate teens about the dangers of distracted driving. Ask students to sign a pledge to never drive distracted. If there is no local Students Against Destructive Decisions chapter, encourage students to start one.

- Include a message about the dangers of distracted driving when speaking to the public on nearly any subject.

- Advocate for stronger distracted driving laws. Legislators often look to police officials for information and direction on traffic safety legislation.

- Have officers distribute brochures warning of the dangers of distracted driving during traffic stops.

- Incorporate distracted driving education in community events and existing crime prevention programs. A number of simulators and demonstrations are available for this purpose.

- Lead by example. Other drivers observe what police officers do while driving.

Police should be aware that distraction-related crashes are underreported and take steps to correct this:

- Move to electronic data collection. Electronic crash reports can accelerate updates and responses to emerging issues.17

- Standardize crash reports by adopting the Model Minimum Uniform Crash Criteria (MMUCC) Guidelines.18

- Train law enforcement officers to understand how their crash investigation data can help prevent future collisions. Accurate data can help prevent deaths and injuries in the future.19

Social media is a way to reach the target audience for distracted driving education. Include traffic safety messaging in Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media posts. The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Governors Highway Safety Association websites have a wealth of information you can use in social media posts.

Enforcement: Public awareness and education programs should be backed up by high-visibility enforcement (HVE). Unlike other initiatives designed to mitigate distracted driving, enforcement can be conducted only by law enforcement. Numerous studies on HVE’s role in addressing other risky driving behaviors have found that HVE ultimately reduces traffic crashes:

Enforcement: Public awareness and education programs should be backed up by high-visibility enforcement (HVE). Unlike other initiatives designed to mitigate distracted driving, enforcement can be conducted only by law enforcement. Numerous studies on HVE’s role in addressing other risky driving behaviors have found that HVE ultimately reduces traffic crashes:

- A study of the Click It or Ticket program in Massachusetts found that “tickets significantly reduce accidents and non-fatal injuries.”20

- A study sponsored by NHTSA found that “the most important difference between the high and low belt use [rates in] states is enforcement, not demographic characteristics or dollars spent on media.…enforcement was much more vigorous in the high belt use states, as shown by an average of twice as many seat belt law citations per capita.”21

- A formal evaluation of the Checkpoint Strikeforce program indicated a 7 percent decrease in alcohol-impaired drivers in fatal crashes associated with the overall program. The participating states of Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have all remained at low-fatality rates as the program has continued.23

Distracted driving presents specific challenges when planning enforcement, especially in states that don’t have laws requiring the use of hands-free devices. Law enforcement agencies have developed a variety of ways to overcome these challenges, and enforcement programs have included the use of large vehicles, like school buses or tractor-trailers, to provide a higher vantage point for officers. Some agencies have gone as far as using a cherry picker positioned as if traffic signal maintenance was being conducted to allow for a better view. Other techniques have included the use of officers in plainclothes or disguises to conduct observations at intersections.24 The IACP has documented several successful initiatives that combine education and enforcement in its Distracted Driving Toolkit:

- The Montgomery County, Maryland, Police Department found that setting up channelization zones to allow better visibility for officers is an effective way of conducting enforcement.

- The Ohio State Highway Patrol used a data-driven approach to identify those areas most prone to distracted driving violations and targeted enforcement and awareness accordingly.

- The Oro Valley, Arizona, Police Department developed and implemented an extensive community awareness campaign, combined with enforcement, after a local ordinance banning the use of handheld devices was passed.25

Numerous promising practices were developed as a result of these efforts that can be replicated in other communities. What is clear is that law enforcement efforts, combined with public awareness and education, can reduce distracted driving and make roadways safer.

Distracted Driving by Law Enforcement

Operating a vehicle, whether in emergency response or when simply patrolling, is a frequent and critical task for police officers. In Roanoke County, Virginia, the 142 officers of the county police department drive over 2 million miles each year. For this reason, law enforcement officers are exposed to the everyday risks of driving at a much higher level than the general population. Unfortunately, these risks can result in tragedies. In 2018, 34 of the 51 officers in the United States who were non-feloniously killed died in traffic crashes.26

Law enforcement officers are not immune from the dangers of distracted driving. Like everyone else, they can be victims of other drivers’ distractions. Additionally, they are subject to the same human temptations related to the use of electronic devices, and an officer on patrol is exposed to even more distractions than the average driver. Aside from both issued and personal electronic devices, officers in a patrol car can be distracted by mobile data terminals (MDTs), police radios, speed measuring devices, license plate readers, and lights and siren controls, among others. In reality, the driver’s seat of a police car looks more like an airplane cockpit than a traditional passenger vehicle.

Emergency vehicle driving is a standard and important part of training for both new and experienced officers. Most of the training is based on the typical driving tasks of steering, speed control, braking, and so forth; it doesn’t necessarily focus on multitasking beyond the use of a police radio. Despite this, there is a perception that officers have a higher level of driving skill that might mitigate the effects of distraction. This does not appear to be true.

Researchers at the University of Washington completed a study to evaluate the impact of a text-based driving distraction on officer driving performance. During the study, 80 experienced police officers participated in an experiment where they drove a 15-minute course on a high-fidelity driving simulator on four occasions. This was done in both rested (72 hours after last shift) and fatigued (immediately after last shift) conditions. The participants drove in conditions both with and without distraction tasks. The results showed that the officer’s distracted driving performance had “significantly greater lane deviation, instances of unintentionally leaving assigned driving lane, and braking latency, than during non-distracted times.”27 These are all factors that increase the risk of traffic crashes. It is safe to say that the results of this study show not only that police personnel are subject to the same risks of distraction as other drivers but that police drivers also do not necessarily have the skills to mitigate the effects of common distractions.

This discussion should frame the issue for police executives. It is known that distracted driving is a problem. Officers are subject to the typical distractions, as well as many more that result from their work, which puts them at risk. This creates a significant officer safety concern. Fortunately, a number of countermeasures can be used to mitigate the risk.

Policies: The foundation for managing risk and guiding critical tasks is good policy. It would be hard to find a law enforcement agency that doesn’t have a policy and procedures governing emergency driving, pursuits, and other scenarios involving vehicles. It is important that distracted driving, particularly the use of handheld devices, be addressed in these policies. Consider the following:

- Communications during an emergency response should be limited to radio transmissions. There is no reason for personnel to be using a handheld device while driving in an emergency mode.

- While more states are passing “hands-free” laws that prohibit the use of handheld devices while driving, some provide exemptions for law enforcement. The use of these exemptions should be limited. There are very few situations that would require the use of a handheld device while driving.

- Drivers should be directed to pull off the roadway when handheld devices must be used. During normal patrol activities or even during response to non-emergency calls, this should not create a significant inconvenience.

- The acceptable use of personal devices should be addressed. These devices are difficult to limit; however, there is no reason for their use while the vehicle is in motion.

Law enforcement officers must provide a positive example of safe driving for the public. The use of handheld devices by officers sets a contrary example for other drivers and diminishes the effectiveness of education initiatives.

Technology: The problem of distracted driving is, in many ways, caused by technology. However, technology can also be a part of the solution. There are many ways to mitigate distraction through automated functions.

- Almost all new vehicles are equipped with Bluetooth systems that allow for the hands-free use of certain cellular functions, especially phone calls. Add-on systems are also available for vehicles without the systems, often at reasonable cost. As discussed previously, VTTI research showed that hands-free conversations are a better alternative than using a handheld device while driving.

- In-car technology that is adaptable to voice control is available, and more options are continually being developed. Currently, some MDT functions (e.g., license plate checks) can be performed via voice input and feedback. Also, lights and siren controls are being adapted for this functionality as well.

- In some cases, positioning in-car technology in a manner that reduces the time that eyes are off the road can help to mitigate distraction. For instance, positioning the MDT screen at a higher level may make it easier for officers to read the screen while the vehicle is in motion. Incorporating in-car technology into one display is also promising. Some manufacturers are installing displays that incorporate MDT, lights and siren, radar, and other functions into the same screen. Other potential improvements include the use of steering wheel controls (when the vehicle permits) to be used for lights and siren, radio, or radar functions. All of these are meant to reduce the time that the driver’s eyes are off the road and his or her hands are off the wheel.

- The MDT creates numerous opportunities for distraction. Software is currently available to limit the number of functions that can be used while a vehicle is in motion. While it’s not possible to completely disable the MDT, limiting its use to functions that must be accessed (for instance accessing calls and navigation) has the potential to mitigate the distracting effects of these systems.

Training: Effective, frequent training on critical tasks is essential for officer safety. Much like policies, virtually every law enforcement agency provides some level of emergency vehicle operations training. Mitigating distractions should be included in this training. It’s likely that most law enforcement personnel, even new recruits, are aware of distracted driving. Unfortunately, most are also probably guilty of doing it. Providing frequent reminders and refreshers can serve to reinforce safe driving. The New York State Police has developed an ongoing program of providing these reminders through messages that appear when MDTs are activated.28

One of the most well-regarded training programs related to officer safety and wellness is Below 100. Below 100 focuses on five tenets for officers: Wear Your Belt, Wear Your Vest, Watch Your Speed, WIN-What’s Important Now, and Remember: Complacency Kills.29 All of these relate to traffic safety and vehicle operations. The final two are most relevant to distracted driving. What’s important now? When operating a vehicle, especially in an emergency situation, the most important task is safe operation and observation of the environment around the vehicle. This simply can’t be accomplished when the driver is distracted. Complacency can affect anyone. Handheld devices and other distractions have become so common that their use can be automatic. Unfortunately, complacency in this regard can be deadly. Below 100 training is available across the United States and is known to be a powerful method of reinforcing important officer safety practices. For those who can’t attend in person, it’s even available online.

Additional research on distracted driving in law enforcement is necessary to help guide agencies toward the most effective practices. Fortunately, studies are underway. The Kansas State University, with funding from the National Institute of Justice, is conducting research to evaluate technology enhancements that control delivery of information in patrol cars and agency policies that guide driving in response to calls for service. This is being done in collaboration with several law enforcement agencies and will include an assessment of officer views as well as analysis of crash statistics to measure the impacts. Results of this work should be available later this year.

Police leaders have an obligation to take every reasonable measure to protect the safety and wellness of their personnel. While it’s impossible to eliminate all distractions, safe vehicle operations require good policies reinforced with training and a commitment to implement effective technology. This is really about balance—the balance between the driver’s desire to access useful technology, even while driving, and the need to ensure the safety of officers and community members. Clearly, the balance must lean in favor of safety.

Conclusion

Until in-car technology or even autonomous vehicles relieves drivers of the need to pay attention, distracted driving will be a critical traffic safety issue. The good news is that better laws are being passed that not only make distracted driving enforcement easier but also provide more specific rules for drivers. Additionally, law enforcement agencies have developed best practices that can be used to mitigate this problem. The challenge for leadership is to use this information and implement effective traffic safety programs for the benefit of community members and police personnel.

Notes:

1National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA), “Distracted Driving in Fatal Crashes, 2017,” Traffic Safety Facts, April 2019.

2NHTSA, “Distracted Driving 2016,” Traffic Safety Facts, April 2018.

3NHTSA, “Distracted Driving 2016.”

4NHTSA, “Distracted Driving 2016.”

5Distraction.gov, “Distracted Driving Global Fact Sheet,” (NHTSA, 2017).

6Distraction.gov, “Distracted Driving Global Fact Sheet.”

7CTIA, “The Wireless Industry.”

8NHTSA, “Policy Statement and Compiled FAQs on Distracted Driving.”

9The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that in 2018, 19,510 persons died from homicide. CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, “Assault or Homicide,” February 27, 2020; NHTSA reports that 36,560 persons were killed in traffic crashes. NHTSA, “U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao Announces Further Decreases in Roadway Fatalities,” press release, October 22, 2019.

10Distraction.gov, “Distracted Driving Global Fact Sheet.”

11 Thomas A. Dingus et al., “Driver Crash Risk Factors and Prevalence Evaluation Using Naturalistic Driving Data,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (March 2016): 2636–2641.

12 Thomas A. Dingus, “What Naturalistic Driving Science Tells Us About Driver Distraction” (presentation, Drive Smart Virginia, 7th Annual Distracted Driving Summit, Roanoke, VA, September 25–26, 2019).

13Dingus, “What Naturalistic Driving Science Tells Us About Driver Distraction.”

14National Safety Council (NSC), Understanding the Distracted Brain: Why Driving While Using Hands-Free Cell Phones Is Risky Behavior (Itsaca, IL: NSC, 2012).

15 Handheld Personal Communications Devices; Holding Devices While Driving a Motor Vehicle, Code of Virginia § 46.2-868 (2020).

16Emily Gliklich, Rong Guo, and Regan W. Bergmark, “Texting while Driving: A Study of 1211 U.S. Adults with the Distracted Driving Survey,” Preventive Medicine Reports (December 2016): 486–498.

17NSC, Undercounted Is Underinvested: How Incomplete Crash Reports Impact Efforts to Save Lives (Itsaca, IL: NSC, 2017).

18NSC, Undercounted Is Underinvested.

19NSC, Undercounted Is Underinvested.

20Howard B. Hall and Anthony S. Lowman, “Traffic Enforcement: Calculating the Benefits to the Community,” Police Chief (July 2017): 42–47.

21 James Hedlund et al., How States Achieve High Seat Belt Use Rates (Washington, DC: NHTSA, 2008).

22Hall and Lowman, “Traffic Enforcement.”

23Tim Harlow, “Minnesota Law Enforcement Gets Crafty in Going After Distracted Drivers,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 25, 2019.

24IACP, Distracted Driving: Promising Practices and Lessons Learned from the Field (Alexandria, VA; IACP, 2019).

25FBI, “Officers Accidentally Killed,”2018 Law Enforcement Officers Killed & Assaulted.

26Stephen M. James, “Distracted Driving Impairs Police Patrol Officer Driving Performance,” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 38, no. 3 (2015): 505–516.

27IACP, Distracted Driving: Promising Practices and Lessons Learned from the Field.

28Below 100, “The 5 Tenets.”

Please cite as

Howard B. Hall, Janet Brooking, and Rich Jacobs, “Law Enforcement’s Role in Distracted Driving: Helping to Keep Our Roadways and Officers Safe,” Police Chief Online, September 23, 2020.