An excessive force incident in one city is no longer an isolated incident with no effect on other cities. This was one of the many lessons U.S. police learned following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on Memorial Day 2020. The civil unrest sparked by the incident spread to major cities, suburbs, and small towns across the United States. Many law enforcement agencies in those communities were unprepared to deal with the public pain that rose to the surface and the anger that was directed at the police.

“We’ve worked hundreds of protests, but this was the first time they were protesting us,” said Major Mike Wood, tactical response commander of the Kansas City, Missouri, Police Department (KCPD).

KCPD prepared for the George Floyd protests like they had so many others, but they soon realized that traditional crowd management techniques would no longer work. Out of necessity, KCPD changed course during the protests in both their public communications strategy and their tactics on the ground to calm civil unrest, address community concerns, and work toward rebuilding trust.

Leading Up to Protests: May 27–28

As it became clear that protests stoked by the death of George Floyd would not remain isolated in Minneapolis, the KCPD Media Unit began working to share expectations with the public. They shared the department’s protest/demonstration policy on all social media platforms and their website, as well as sharing KCPD officers’ commitment to supporting community members’ First Amendment rights.

They also created a new webpage to answer the many questions coming in from the public. This frequently asked questions page linked community members to the department’s Response to Resistance policy. It explained KCPD’s training in many areas, including de-escalation, mental health awareness, bias, racial profiling, stress management, tactical communication, and other topics. Community members also asked about the department’s body-worn camera policies. KCPD did not yet have body-worn cameras, and the page explained the funding issues surrounding that while highlighting the dash-cam capabilities already in place. The page also directed users to the full list of policies and procedures already on the department’s website.

The Protests Begin: May 29

Kansas City’s protests began in earnest on Friday, May 29, at a park on the Country Club Plaza (Plaza), a historic upscale shopping district. On-duty proactive squads from the Tactical Response and Traffic Enforcement divisions initially responded. Several hundred people gathered, and in the daylight, the protests were peaceful. An image of police officers holding an “end police brutality sign” alongside protesters even went viral. But, as the sun set, the mood changed.

Protesters began to push into the street and throw projectiles—mainly rocks and bottles—at police officers who were trying to contain the protesters in the park. Officers on the ground quickly realized they were outmatched and would not be able to contain the crowd. Officers deployed tear gas, pepper spray, and less-lethal munitions in attempts to maintain order. Commanders called for additional personnel to respond. Stores and restaurants on the Plaza were shuttered.

A single public information officer (PIO) provided periodic updates to the media that evening.

The Worst Day: May 30

As the weekend began, the gravity of the situation was becoming more apparent to police. Personnel were called in from around the department, and days off were cancelled. Chief Richard Smith made a mutual aid request to 15 state and local agencies in both Missouri and Kansas; all 15 agreed to provide personnel either to work the skirmish line at the protest or cover calls for service so KCPD patrol officers could work the protest.

This was made possible by previous legislative efforts in both Missouri and Kansas to allow law enforcement officers in both states to provide mutual aid across state lines. For a city situated on a state line like Kansas City, Missouri, this capability proved to be critical.

The KCPD Media Unit also realized additional personnel were needed. Three PIOs responded to the protest area, as opposed to the one assigned to it the previous day. They created a designated media staging area far enough from the center of the protests to be safe from thrown projectiles but close enough to see protesters. The PIOs began to provide hourly updates to the media from roughly noon to midnight. Non-sworn public relations staff managed social media at home, mirroring the messages from the PIOs. They also tried to address concerns and answer questions, though at times the volume of posts asking for a response became impossible to keep up with.

Police continued to try to hold the skirmish line to prevent protesters from spilling out of the Plaza into the streets. Protesters filmed and shared videos of police using pepper spray during an arrest, which would later become a major issue as the post became viral, drawing scrutiny from around the world. Again, as darkness fell, protesters became violent. Every police officer working the skirmish line was struck by projectiles ranging from small explosives to cans of beans. One officer suffered a concussion, and a thrown rock lacerated another officer’s liver. Rioters forced their way through the police line and broke into and looted numerous retail stores on the Plaza. They also set fire to dumpsters and police and television news station vehicles.

In turn, police again deployed tear gas, pepper spray, and less-lethal munitions. The public message, delivered both by PIOs to the media and by public relations staff on social media, was that the protest had been declared an unlawful assembly, and these tactics were needed to maintain peace and order.

Ongoing Protests and Conflict: May 31–June 5

Sunday, May 31

A public relations specialist went to the city’s Emergency Operations Center to monitor and post to social media alongside other department members and commanders. The three PIOs alternately worked the line with other officers and updated media on an hourly basis. One of those PIOs, Captain David Jackson, made contact with one of the lead protest organizers and invited the organizer to one of the hourly media briefings to explain his demands and reasons for protesting. This was the beginning of a relationship that would later prove critical to calming the unrest.

In the early evening, commanders agreed to let protesters into the streets. This de-escalated tensions. Officers blocked streets to allow the group of about 500 to march safely around the Plaza and nearby neighborhoods.

As darkness fell, however, violence erupted again. One of the PIOs at the scene worked with the public relations specialist at the Emergency Operations Center to share photos of items that had been thrown at officers to justify officers’ use of tear gas, pepper spray, and less-lethal munitions. As with other protest updates, the PR specialist shared these images on the department’s Twitter account, where it received overwhelmingly negative feedback showing little sympathy for the officers.

Monday, June 1

Top command staff asked Media Unit members to double down on this “rocks and bottles” messaging. They wanted the public to know about the violence that was being perpetrated against officers and why officers were deploying tear gas and less-lethal munitions against the protesters. The public relations specialist managing social media advised her chain of command of how poorly the photos of items thrown at officers had been received. After some discussion, the Media Unit members agreed that no matter what happened, the police department could no longer portray themselves as victims. The protesters represented a group of people who were hurting deeply after the death of George Floyd, and, in some cases, years of real and perceived oppression and mistreatment. For the police to claim they were the ones being mistreated came across as tone deaf.

The Media Unit convinced command staff that the message needed to change from “rocks and bottles” to “we hear you.” PIOs and public relations specialists highlighted the tactical changes officers were making on the ground of the protest, such as allowing protesters into the streets and blocking roads for them. Although violence was still being perpetrated against officers, PIOs downplayed it in media briefings. Chief Smith met with protesters at the Plaza and held a joint press conference with Mayor Quinton Lucas.

June 1 was the last night the protest was declared unlawful and the last night tear gas was used.

As the message was shifting, Governor Mike Parson deployed the Missouri National Guard to Kansas City to protect police facilities. Commanders made the specific decision to keep them away from the protests on the Plaza.

Tuesday, June 2

The video of a protester being arrested and pepper-sprayed that had been filmed on Saturday was fully viral by Tuesday to the extent that it was being shared by celebrities and was featured on HBO’s Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, among other outlets. The department’s social media — even posts from six months prior to George Floyd’s death — were attacked with negative comments. Command staff decided the Media Unit would be the central repository for feedback regarding the protest response. All angry phone calls from around the United States also got directed to the Media Unit. In spite of this intense scrutiny, KCPD very consciously did not stop communicating. Too often, law enforcement agencies go silent in a crisis. It is the worst time to do so. If the agency does not tell their story in a crisis, someone else will. So KCPD’s hourly media updates and regular social media posts continued. Most of the social media posts focused on how the department was listening to concerns and how to file complaints.

The social media onslaught was unlike anything the Media Unit had experienced since launching its accounts in 2009. No amount of best practices in social media engagement seemed to make a difference. Public relations specialists were later able to determine many of the negative accounts were bots. A PR specialist blocked four Twitter accounts that were particularly abusive for a few days. When she unblocked them, only one of the four accounts was still in existence. The other three had been specifically set up to troll the KCPD account, and when they could no longer see the posts, these false accounts disappeared.

Carnegie Mellon University’s Center for Informed Democracy and Social Cybersecurity reported in May 2020 that between 45 and 60 percent of all Twitter accounts discussing COVID-19 were bots, many spreading misinformation. Most of them were centered outside the United States.1

“Social media bots are used to automatically generate messages, advocate ideas, act as a follower of users and as fake accounts to gain followers themselves,” cybersecurity firm Imperva states. “Social bots can be used to infiltrate groups of people and used to propagate specific ideas. Since there is no strict regulation governing their activity, social bots play a major role in online public opinion.”2

Dr. Jeanna Matthews, a professor of computer science at Clarkson University, said one of many bot managers’ primary goals is to sew division in democracies.3 KCPD’s Media Unit certainly saw that playing out on the agency’s social media. After the protests subsided, there was a marked reduction in negative posts from suspected bot accounts.

As the tenor on social media changed, so did questions from traditional media. In the past, when members of the public accused KCPD of excessive force, reporters would phrase the questions to PIOs more as “Tell me about what happened.” During and since the protests, many reporters—especially from national publications—now ask, “Why did police do this?” This implies that they believe the accusations of excessive force as recounted by the aggrieved individual without additional context and discounts that additional context or further investigation often exonerates officers of any wrongdoing.

While PIOs and public relations specialists dealt with reporters and social media users, tactical commanders were changing officers’ approaches on the ground. They began pulling officers off of the skirmish line, thereby eliminating direct confrontations between officers and protesters. Officers also met with pastors from throughout the city who wanted to pray for both the officers and protesters.

Wednesday, June 3

The same pastors who prayed with officers helped organize a unity march between KCPD and community members. This event, attended by more than 1,000 people, featured officers marching alongside protesters, asking and answering questions. It proved to be the embodiment of the newly adopted “we hear you” messaging.

At the same time, a community philanthropist donated more than $2 million to begin the long-awaited purchase of body-worn cameras for KCPD. In coordination with the Police Foundation of Kansas City, Chief Smith announced this donation at the Unity March. Body-worn cameras had been one of the protesters’ demands.

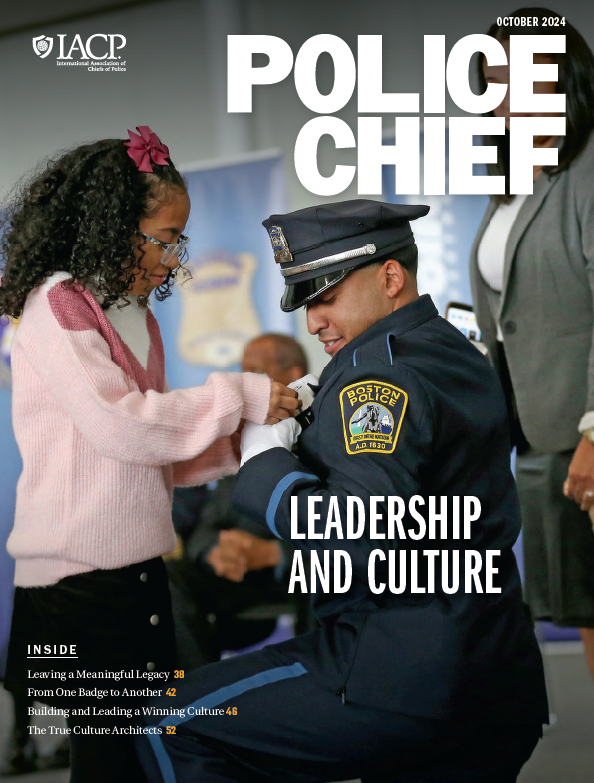

Image courtesy of KCPD

While things were looking up from the outside, officers on the ground were still getting pummeled with rocks and bottles. They were upset that the department was no longer sharing what was happening to them. While the Media Unit and some commanders knew that “rocks and bottles” messaging was creating further division and anger toward officers, the reason for the shift to “we hear you” messaging, it became clear that the reasoning did not get adequately communicated to officers on the ground.

Thursday, June 4

KCPD’s governing body, the Board of Police Commissioners, had an emergency meeting to discuss reforms and steps forward. The board decided to meet some of the demands made by protesters, including having an outside agency investigate officer-involved shootings and implementing a confidential way for officers to report misconduct of other officers through the Human Resources Division, instead of to their chain of command.

Media Unit staff broadly shared the message that the department was listening and making the changes the community wanted.

Friday, June 5

Protesters moved several miles north from the Plaza to city hall and the KCPD headquarters, which are across the street from each other. About 1,500 people began to press toward the headquarters at noon. This time, they confronted a line of not just KCPD officers but also the National Guard soldiers who had been assigned to protect police facilities. Tensions escalated as officers feared the police headquarters would be breached (as many others across the United States had by this point).

Once again, relationships prevailed. Captain David Jackson found the organizer he had connected with and asked if the organizer would agree to lead the protesters on a march through downtown. The organizer agreed. With Captain Jackson alongside him, the organizer was able to turn the protesters away from police headquarters on a lengthy march. Police again moved to block traffic for the marchers’ safety.

When the group returned to headquarters, they mostly disbanded. Those who remained struck up conversations with individual officers. Although the topics of conversation were difficult, this provided an excellent chance for officers and protesters to hear each other’s concerns, something that had not been possible in the more confrontational skirmish-line setting.

That evening, activists had organized another protest at one of KCPD’s stations, East Patrol Division. About 100 protesters showed up, but they were met with nearby residents who were determined not to let any harm come to “their police station.” East Patrol sits in an urban-core neighborhood, and its members have invested heavily in community policing. When the new station opened in 2015, it even included a computer lab and gymnasium for community use. East Patrol holds regular community outreach events and that investment paid off. Neighbors stood up so no one from outside their community would damage the station or hurt the officers with whom they had formed positive relationships.

Recovery

Protests dissipated in the days and weeks that followed. Plaza businesses, which had closed during the most intense week of civil unrest, gradually repaired their broken storefronts and reopened. Police maintained their hands-off approach for subsequent, smaller protests, and these protests remained peaceful. Officers remained ready but out of sight unless needed. Skirmish lines were no more.

The Media Unit faced mounting internal pressure to tell positive stories about the department, but by monitoring social media, the unit members knew the time was not yet right. They told commanders that any attempts to broadcast how great police were in a time of U.S.-wide grief over police brutality would be tone deaf. Instead, the Media Unit continued to emphasize the reforms that were under way. As many members of the public started to understand that KCPD had listened to and acted on calls for change, the Media Unit was able to transition to social media messages thanking those who had donated bottled water, snacks, and meals to officers. Next, they shared user-generated content posted by community members thanking KCPD for everything from assisting when the power was out at a low-income senior living complex to finding a lost dog. After several weeks of those posts, the Media Unit finally shifted to once again telling the positive stories of the department.

Public relations specialists also had become more adept at identifying bots and trolls, looking for signs of automation, a lack of personal posts, and whether posters’ followers appeared to be other bots. Knowing who was real and who wasn’t helped staff employ tried-and-true engagement strategies that led to meaningful discussions with real residents who had genuine questions and concerns.

Captain Jackson and other KCPD members who came to know protest organizers during the week of civil unrest have maintained those relationships. They maintain regular contact in various ways, from text messages to lunches.

Lessons Learned

- Be prepared, but not constrained to “the way we’ve always done things.”

- Department leaders had recently lobbied state legislatures to allow for mutual aid across state lines.

- A webpage dedicated to community questions about police training and reforms simplified responses to community concerns.

- Switch up the message (e.g., from “rocks and bottles” to “we hear you”), and pair it with similar actions of de-escalation on the ground to calm tensions.

- Actions must accompany words. KCPD listened to protesters and implemented multiple reforms. Without those changes, “we hear you” would have been an empty platitude.

- Allowing protesters in the street and removing the skirmish line reduced violence against officers, property damage, and the need for teargas and less-lethal munitions.

- Continue to communicate, even in crisis situations. Swim sideways with the tide.

- Reliable and predictable distribution of information to the media proved critical throughout the civil unrest. This let residents know their 911 calls would be answered, order would be maintained, and that KCPD was making changes.

- If an organization goes silent in a crisis, other voices will fill the void, and those voices likely will not be accurate. Communicating amid a crisis is hard and counterintuitive, and negative feedback will be inevitable, but it is necessary to get the organization’s message out.

- The bots and trolls of social media wanted to make Kansas City and communities across the United States appear more divided than they really are. Recognizing who was real and who wasn’t helped KCPD Media Unit members get an accurate pulse on residents’ sentiment.

- Don’t forget to prioritize internal communication. KCPD failed to explain to rank-and-file officers about the reason for the change from “rocks and bottles” messaging to “we hear you” messaging, which fostered some resentment.

- Build relationships with protest organizers, which can calm tensions at crucial moments.

- Meeting and forming relationships with protest leaders proved far more effective at stopping violence against police than tear gas or pepper spray.

- Maintaining those relationships continues to avert other potential civil unrest issues in the months since this crisis.

The civil unrest of 2020 resulting from a national high-profile police use-of-force incident prompted KCPD members to rethink both their tactical and communication strategies. To maintain peace and trust, field force tactics and messaging had to change to address the concerns of the community. KCPD is using the lessons learned from these incidents to revise policies and practices going forward. 🛡

Please cite as

Sarah Boyd and Jake Becchina, “No More Rocks and Bottles: Lessons Learned in Crisis Communication,” Police Chief Online, March 3, 2021.