In July 2017, state and local leaders in Utah met to address a burgeoning crime problem in downtown Salt Lake City, near Utah’s largest homeless shelter. During a span of a few years, the Rio Grande District of Salt Lake City had become a hotbed of crime and disorder fueled by an estimated 2,500 individuals living on the streets.

A series of events in the summer of 2017, culminating in three murders, the violent assault and robbery of a minor league baseball player, and a car crash near the shelter that killed one person and injured several, left state and local leaders determined to find a solution.1 The surge of violence also prompted a prominent advocate for those experiencing homelessness in Utah to voice support for changes.2

Operation Rio Grande—A Call to Action

|

Addressing the Growing Crisis in Utah As Utah’s capital, Salt Lake City has historically provided the majority of resources for Utah’s vulnerable populations, including those experiencing homelessness. Individuals seeking services typically made their way to Salt Lake City’s Rio Grande District. As major steps were taken to revamp the delivery of homelessness services in Utah, the district’s crime problem persisted and continued to grow. The encampment in the area known as “The Block” was growing every day. For years, the Rio Grande District faced challenges with crime and disorder. The problem accelerated as several factors converged including • the opioid crisis; Criminals intent on profiting from the increasing disorder saw an opportunity and moved in. In a few short years, an open-air drug market supplied drugs from the Rio Grande District to individuals in the vicinity and across the state. |

Plans had been underway since 2015 to replace the one large downtown emergency shelter and build three smaller resource centers by 2019, but crime and violence had escalated. In response, the Salt Lake City Police Department poured resources into the area, but challenges persisted. The growing concerns led to community conversations, media reporting, and frustration. Finally, in the spring of 2017, it reached a tipping point when House Speaker Greg Hughes of the Utah State Legislature moved his office from the Utah State Capitol to a vacated office in the Rio Grande District in an effort to garner attention and support for change.

In July 2017, a series of emergency meetings gave birth to Operation Rio Grande. The three-phase approach was designed to (1) restore order and public safety in the Rio Grande District, (2) provide for increased assessment and treatment resources, and (3) provide increased work opportunities for those in need.3

While existing shelter space was available for those illegally camping in public, jail and treatment capacities were lacking. Policy makers brokered deals to free up 300 jail beds for the operation and add 275 new residential treatment beds, more than doubling the treatment capacity in the state. Leaders also took a major step in closing Rio Grande Street to build a safe space with enhanced services. Individuals seeking assistance received a coordinated-entry services card and access to a safe location for seeking services.

The cost of the operation was split between the state, county, and city. The Utah legislature funded an additional 47 sworn officer positions for the Utah Department of Public Safety through June 2020. The Utah Department of Public Safety, Salt Lake City Police Department, Unified Police Department, and Utah Department of Corrections formulated a plan to restore order in the Rio Grande District.

Operation Rio Grande Begins

On August 14, 2017, officers from multiple agencies deployed into the Rio Grande District to restore order. Because circumstances varied greatly for individuals in the area, law enforcement activities were divided into three main areas of emphasis:

- Increased uniformed patrol activities

- Specialized criminal enforcement

- Community outreach and support

Increased Uniform Patrol Presence. The addition of officers to the Rio Grande District increased visibility of law enforcement in the area. Due to increased police presence via foot patrols, criminal actors were unable to openly deal drugs and were less likely to victimize vulnerable individuals. Officers had more opportunities to connect with community members and help those in need. The additional personnel also allowed the Salt Lake City Police Department to deploy resources to other parts of the city to address similar challenges.

Specialized Criminal Enforcement. A top priority of the operation was to dismantle the district’s open-air drug market and remove violent criminals from the area. The State Bureau of Investigation deployed a narcotics unit to work with the Salt Lake City Police. Using intelligence-led policing concepts, including network analysis and focused deterrence, teams worked to remove the most egregious offenders from the area. As the operation progressed and crime patterns changed, the State Bureau of Investigation deployed similar approaches in other areas.

Community Outreach Teams. Prior to Operation Rio Grande, the Salt Lake City Police Department formed the Community Connection Center and added eight social workers to the department. Officers and social workers deployed in a co-responder model. To supplement their effort, the Utah Highway Patrol also formed an outreach team consisting of five troopers and two social workers to work in the Rio Grande District.

What’s more, law enforcement coordinated closely with the Utah Department of Workforce Services and service providers to support Phase Two and Phase Three efforts.

Operation Rio Grande Delivers

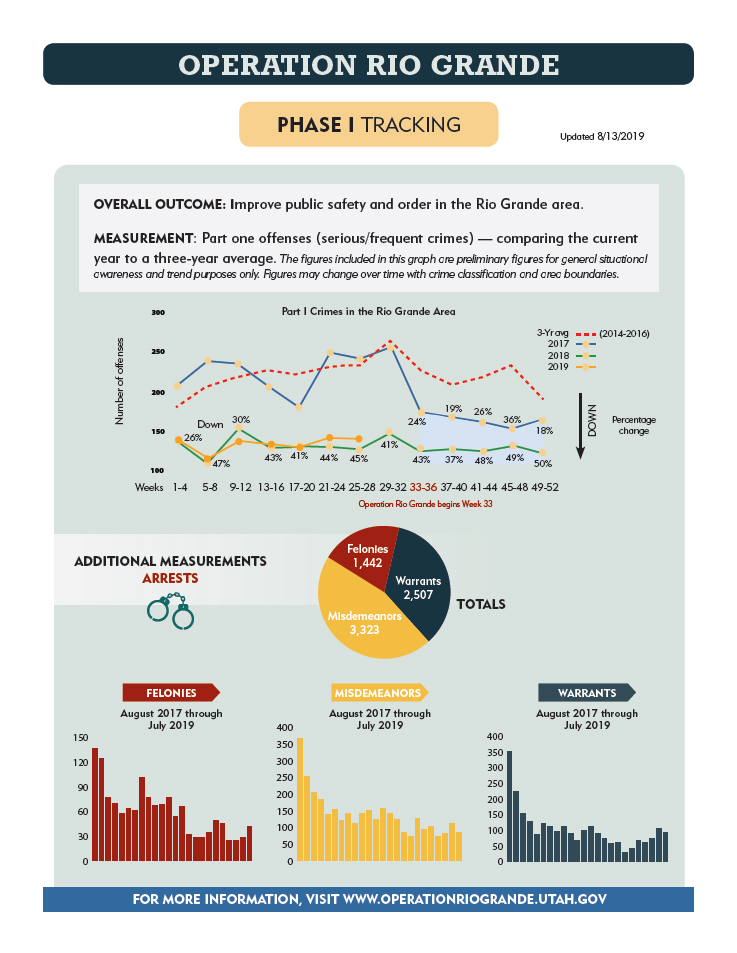

A few weeks into the operation, improvement was evident. The street population decreased significantly, and the aesthetics of the area improved. The trash, feces, and syringes that previously littered the area were reduced, improving public health and safety. The open-air drug market was dismantled, and drug use and dealing reduced. Operation Rio Grande has led to more than a 40 percent decrease in serious crimes (Part I offenses, as defined by the FBI) for 2018–2019 when compared to the 2014–2016 average (See Figure 1).4

FIGURE 1: Phase 1 Outcomes

While restoring public safety was the goal for Phase I of the operation, some stakeholders were concerned law enforcement efforts would discourage individuals from seeking services. To assess this concern, operation leaders monitored two key measures:

- Number of daily shelter check-ins5

- Number of meals served by Catholic Community Services

Both measures have shown little or no change throughout the duration of the operation, though the street population and crime have decreased significantly. Today, more individuals than ever are accessing services and treatment. Forty-seven state troopers and state agents continue to work with the Salt Lake City Police to maintain public safety in the area and assist with the transition to the new services delivery model.

Operation Rio Grande Strategies

Operation Rio Grande required various strategies and encouraged a collaborative approach. A few of the following strategies contributed to the operation’s success.

Community Support and Engagement. An undertaking with the scope and size of Operation Rio Grande is not without controversy. Building trust with community stakeholders was critical. Policy makers from both political parties in Utah worked with service providers, business leaders, law enforcement, advocacy groups, the media, and representatives of the district’s vulnerable populations to formulate a plan. Ongoing public meetings and media engagement kept important stakeholders and the public informed. While differences of opinion at times existed, established relationships allowed for problem-solving and best outcomes.

Statewide Coordination. At the onset of the operation, many municipalities expressed concern that Operation Rio Grande would simply push the problem from downtown Salt Lake City to other municipalities. State leaders committed to providing legislative and coordination support. The Department of Public Safety responded to all complaints or requests for assistance from other jurisdictions, and all requests were accommodated without overwhelming city and police department resources.

Under state direction, a working group was established to develop a resource guide, Developing Your Community Response to Unsheltered Homelessness, which was made available online.6 The Department of Public Safety and Department of Workforce Services also met with local municipalities to hear concerns and discuss solutions for helping unsheltered homeless populations.

Hot Spot Policing. Increased police presence in the Rio Grande District reduced crime. While problems to other areas increased in some cases, Salt Lake City saw an overall decrease in serious crimes of nearly 25 percent across all areas of the city.7 The state of Utah overall saw a decrease in serious crime in 2017 by 5.38 percent.8

A study funded by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) suggests that hot spot policing is effective in reducing crime and disorder. The study also found that “hot spot policing, particularly problem-oriented policing, is more likely to reduce crime in the surrounding areas than it is to lead to crime moving to that area.”9 The outcomes of Operation Rio Grande support this theory on hot spot policing.

Altering Place Characteristics. A review of the research on hot spot policing states,

While arresting offenders remains a central strategy of the police and a necessary component of the police response to crime hot spots, it seems likely that altering place characteristics and dynamics will produce larger and longer-term crime prevention benefits.10

Other government units, in coordination with law enforcement, used important strategies to improve outcomes. The creation of a safe space for accessing resources, regular street cleanings, beautification projects, and strategic placement of new resources all contributed to positive changes in the area. Nuisance abatement laws were effective in reducing criminal activity occurring at a particular motel in the area. Police also worked with businesses on trespassing affidavits to stem after-hours criminal activity. Altering place characteristics of the neighborhood was a major factor in crime reduction and increased safety.

|

Crime and Policing Among Vulnerable Populations Many communities across the United States today are facing similar challenges to that of the Rio Grande District, with unacceptable levels of crime and violence. Addressing crime among vulnerable populations, including those experiencing homelessness, can be particularly challenging and controversial. A recent publication by the International Association of Chiefs of Police, Policing in Vulnerable Populations, reads, Public safety and well-being cannot be attained without the community’s belief that their well-being is at the heart of all law enforcement activities… it is critical to help community members see police as allies rather than as an occupying force.* A thoughtful approach to ensuring public safety while protecting individual rights and building community trust is critical. Heavy-handed tactics can lead to the loss of community trust and support, perceived or real criminalization of vulnerable individuals, and growing criminal records for those facing life challenges. A limited response can lead to continued victimization of vulnerable individuals, failure to restore public order, morale issues among officers, and a loss of confidence in a police department’s ability to safeguard the community. Solutions to the challenges are varied, ranging from prevention programs and criminal enforcement to community outreach and government-wide coordination. A blended strategy with all stakeholders contributing will lead to the best outcomes.† Notes: * International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Policing in Vulnerable Populations, Practices in Modern Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2018). † IACP, Reducing Violence and Crime on Our Streets: A Guide for Law Enforcement Leaders (Alexandria, VA: IACP, 2018). |

Co-Responder Model. Both the Salt Lake City Police Department and the Utah Highway Patrol deploy specialized outreach teams with licensed clinical social workers effective in crisis response and knowledgeable about available resources. While the Salt Lake Police Department directly employs social workers, the Utah Highway Patrol contracts with local mental health organizations to obtain social workers.

Diversion from the Criminal Justice System. Salt Lake County partnered with Utah Highway Patrol to start a program to identify and divert individuals frequently arrested for low-level offenses out of the criminal justice system. These individuals do not typically qualify for traditional drug court. The program seeks to fill the gap.

Law enforcement, service providers, prosecutors, legal defenders, and courts work together in the best interest of an individual to assess and offer the appropriate treatment. A social worker for the Utah Highway Patrol provides case management and intensive support through treatment and adjudication. The individualized approach and system alignment lead to improved outcomes and cost savings.

New Specialty Court Program Focused on Co-Occurring Population. Many of the individuals in and around the homeless shelter have both mental health issues and substance use disorders and are in need of greater hands-on case management. Salt Lake County started a new specialty court program focused on addressing the needs of individuals with co-occurring challenges. Salt Lake County populated the new court by working with prosecutors, legal defenders, treatment providers, and community partners to offer the program to individuals in jail, in some cases connecting the individuals to needed treatment services only days after arrest.

Expansion of Health Care for the Justice Involved. On November 1, 2017, Utah obtained a waiver from the U.S. federal government to expand Medicaid health care coverage to individuals involved in the justice system, participating in mental health and drug courts, or experiencing chronic homelessness. This unique program, called Targeted Adult Medicaid (TAM), provided needed health coverage to individuals coming out of incarceration who were previously uninsured. To date, state and local leaders have enrolled more than 4,000 people, and close to 2,000 individuals involved in Operation Rio Grande have accessed treatment services in Salt Lake County.11

Criminal Record Expungement. Individuals seeking employment and housing for long-term stabilization may have limited options due to past criminal convictions. Operation Rio Grande sponsored an expungement day to help several hundred individuals expunge qualifying criminal records. Volunteers assisted qualifying individuals with the expungement process. In the 2019 legislative session, the state passed automatic expungement for low-level offenses — an important step in helping individuals move forward.

U.S.-wide research shows housing and peer support are effective in reducing recidivism and improving long-term stabilization.

Sober Living Program. Salt Lake County developed a program to provide rapid rehousing support to individuals completing residential treatment, coming out of incarceration, or participating in the drug court program. The sober living program provides up to six months of short-term housing and recovery support for individuals, allowing for their gradual acclimation into society. Since January 2018, Salt Lake County has housed more than 500 clients in the sober living program. Eighty-one percent of those clients are still housed or have had neutral or positive exits. U.S.-wide research shows housing and peer support are effective in reducing recidivism and improving long-term stabilization.12

Increased Job Opportunities. The Department of Workforce Services and Steve Starks of the Utah Jazz led the effort to increase job opportunities for those seeking assistance. Teams worked with employers, held job fairs, and provided job counseling sessions. More than 566 employment plans were developed, with several individuals receiving employment opportunities.13 In fact, one person arrested as part of Operation Rio Grande received treatment and transitioned to long-term employment with the Salt Lake County Mayor’s Office.

Lessons Learned from Operation Rio Grande

While many lessons were learned through the operation, there are a few key points that merit emphasis.

1. Balancing Accountability to the Law and Support for Individuals

Leaders acknowledged from the inception of Operation Rio Grande that the problem could not be solved with arrest and incarceration alone. However, it was also evident that the crime had reached intolerable levels and was negatively affecting the environment and delivery of services to the community’s vulnerable populations.

Officers were directed to set expectations and restore order. Officers were given discretion on how to hold individuals accountable; however, they were also directed to support the people they encountered and assist in meeting their needs. The majority of individuals in the area met the expectations established by law enforcement. When people did not, officers took the appropriate action using a commonsense, compassionate approach based on individual circumstances.

Requiring accountability of persons in difficult circumstances and policing with compassion are not mutually exclusive approaches. Both are required for the good of the individual and the public. Many individuals who received treatment as a result of the operation said it was the persistence of officers that made the difference.

2. Understanding the Community

When engaging in an effort like Operation Rio Grande, it is important to understand the subpopulations existing within the larger community and then create tailored approaches to addressing those populations’ needs. The same applies to individuals and their specific needs. A key component in Operation Rio Grande was officer engagement. Officers walked the area, talked with people, and learned their circumstances. This engagement helped officers understand individual needs and community dynamics. The engagement led to better identification of criminals while helping vulnerable, noncriminal community members.

The Department of Public Safety worked with the downtown shelter operator to improve safety conditions in the shelter. Officers conducted meetings with the shelter operator and patrons to develop best strategies. Contrary to what many believed, patrons of the shelter voiced support for increased law enforcement presence as a means of deterring crime in the shelter.

3. Law Enforcement and Service Provider Coordination

Operation Rio Grande increased communication between law enforcement and service providers. A group of law enforcement officials and service providers came together to develop safety and security policies for the new resource centers and a guide for municipalities on working with unsheltered populations. Monthly meetings are now held with all resource center operators and the respective law enforcement agencies to discuss best practices and coordinate solutions.

Officers regularly contacting those who are unsheltered and experiencing homelessness can become frustrated with limited options for addressing the needs of the vulnerable. Law enforcement officers also have a wealth of information that can be helpful to service providers. The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness recently released a guide that supports strengthening partnerships between law enforcement and homelessness service systems.14 The resource guide offers suggestions for better coordination.

4. Officer Training and Engagement

Officers who are well trained, supported, and genuinely want to make a difference are most effective in serving vulnerable individuals. A task force on policing vulnerable populations found,

The most effective officers are those who are trained to read all varieties of people, situations, and circumstances and to adapt accordingly. Adaptive approaches are especially important for policing vulnerable populations.15

Early in the operation, individuals with abscesses from drug use and poor health were prevalent in the area. One man explained he was arrested by a trooper but refused at the jail due to his abscess. The trooper arrested him a second time a few days later. This time, the trooper had made prior arrangements for medical treatment. He was then booked into jail where he was offered enhanced treatment opportunities through the operation. He accepted help and was given treatment. A year later at his Operation Rio Grande drug court graduation, he was able to tell his story and thank the trooper for his dedication and persistence.

Many other stories and examples of dedicated officers demonstrate that engagement and adaptability to individual circumstances can truly make a difference. Many individuals receiving treatment have expressed their appreciation for the improvements to the environment and the help received from law enforcement.

5. The Need for Political Leadership and Support

Addressing the needs of vulnerable populations requires engagement and support at the highest levels of government. Political leaders were critical to the success of Operation Rio Grande. Leaders from both political parties, at a state and local level, set aside differences to address a complex, difficult challenge. They coordinated with stakeholders and set the vision. Leaders then provided the necessary resources and support. When controversy or criticism arose, political leaders backed the operation, including law enforcement efforts. Political leaders who have vision and are supportive are key in solving difficult challenges that lead to real improvement and lasting change.

Conclusion

While there is still much to be done for Utah’s vulnerable populations, much good has resulted from Operation Rio Grande. While too many still face homelessness, addiction, and mental health challenges, awareness of the problem, treatment options, and affordable housing capacity are growing. While too many still face criminal justice sanctions, diversion programs are available and growing. While crime still occurs there, the Rio Grande District is much safer today. While more can be done to align criminal justice and crisis delivery systems, coordination and information sharing are better than ever.

As Utah transitions from Operation Rio Grande to a new homelessness service delivery model, continued stakeholder coordination and a sustained effort are critical. Utah will continue to find solutions and support its most vulnerable in the years ahead. d

Notes:

1 Ben Winslow, “Political Leaders Promise a New Attack on Crime in SLC’s Troubled Rio Grande Neighborhood,” Fox 13 Salt Lake City, July 26, 2017.

2 Pamela Atkinson, “Operation Rio Grande Is Saving Lives,” The Salt Lake Tribune, August 26, 2017.

3 State of Utah, “Operation Rio Grande,” 2017.

4 U.S. Department of Justice, Uniform Crime Reporting, “UCR Offense Definitions”; State of Utah, “Operation Rio Grande: Phase I Tracking,” August 2019.

5 State of Utah, “Operation Rio Grande: Phase I Tracking.”

6 Utah Department of Public Safety and Utah Department of Workforce Services, Developing Your Community Response to Unsheltered Homelessness.

7 Salt Lake City Police Department, CompStat Report, Vol. 5, no. 25 (June 2019).

8 Utah Department of Public Safety, Crime in Utah, 2017.

9 Robyn Mildon and Karen Harries-Rees, “Hot Spots Policing Is Effective in Reducing Crime,” Campbell Plain Language Summary, 2015.

10 Anthony Braga, Andrew Papachristos, and David Hureau, “Hot Spots Policing Effects on Crime,” Campbell Systematic Review 8 (2012).

11 State of Utah, “Operation Rio Grande Phase 2 Tracking,” August 2019.

12 State of Utah, “Operation Rio Grande Phase 2 Tracking.”

13 State of Utah, “Operation Rio Grande Phase 3 Tracking,” August 2019.

14 U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Strengthening Partnerships Between Law Enforcement and Homelessness Services Systems, June 2019.

15 IACP, Policing in Vulnerable Populations: Practices in Modern Policing (Alexandria, VA: IACP Law Enforcement Policy Center, 2018).

Please cite as

Brian Redd, “Operation Rio Grande,” Police Chief Online (October 2019).