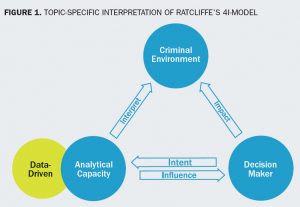

Numerous Western police organizations, including the Danish National Police, have articulated their deployment of intelligence-led policing (ILP)—a goal-oriented model for policing with a focus on informed decision-making, harm reduction, disruption, and prevention.1ILP is often best described and understood as a 4i-model (see Figure 1) with a focus on interpreting the criminal environment as an active activity, to influence the decision maker, who uses the knowledge to impact the criminal environment.2

In the Danish context, ILP is defined in the 2018 Intelligence and Analysis doctrine as a specific strategy or model of policing, strongly influenced by Professor Jerry Ratcliffe’s definition of ILP:

Intelligence-led policing emphasizes analysis and intelligence as pivotal to an objective decision-making framework that prioritizes crime hot spots, repeat victims, prolific offenders and criminal groups. It facilitates crime and hard reduction, disruption, and prevention through strategic and tactical management, deployment, and enforcement.3

The overall aim of ILP is to transform the policing enterprise into a more proactive, less incident-based organization with a strong emphasis on analysis-driven products to support decision makers.

Today, crime is characterized by its unpredictable and volatile nature, which necessitates solid decision-making capabilities within policing. ILP and, more specifically, the dialogue and nexus between the analytical data-driven capacity and the decision maker is considered a fundamental element of informed and timely decisions.

|

While this is not a new concept, the data landscape and data-driven information resources available to analysts have increased enormously. This has consequently increased the risk of depriving managers of the ability to make evidence-based or intelligence-led decisions.

Lord Stevens, a previous commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police Service, once explained the challenges in policing using the analogy of a fast-flowing river, sweeping hundreds of people away in its current. Stevens stated that the traditional policing response would be for police officers to jump into the river and help as many people as possible out of the river, instead of going upstream to determine why and how people are falling into the river in the first place. He went on to say, that “so begins a reactive cycle of uncontrolled demand and equally uncoordinated response.”4 This analogy illustrates the need for a proactive approach (i.e., ILP and other policing paradigms such as evidence-based policing and problem-oriented policing) to understand the underlying why of crime trends. It also underpins the need for analysts to be able to break down and externalize findings so as to influence, legitimize, and support the decision-making process.

Data-driven policing resides at the core of the intelligence process. It has become more and more evident that analysis and analysts who work with data and intelligence have become the heart of policing knowledge management. As Dr. Eric Halford, associate researcher and assistant professor at Rabdan Academy recently stated on social media, “Analysts are the blood of any law enforcement agency. Grossly undervalued…”5

Maja Bisgaard Olesen, an analyst with the Copenhagen Police, agrees, stating,

In Copenhagen, ILP is not just something we talk about, it’s something we do. It’s an integral part of how we, as analysts, support ongoing investigations; do in-depth analyses on some of the most serious issues we are dealing with; and apply evidence-based techniques to combat group-related violence in the city.6

The Data-Driven Landscape

The complexity of crime will inevitably call for change and modernization. This, in turn, demands new mindsets, diverse skills, and competencies. In his recent book, Rebel Ideas, journalist Mathew Syed claims that a lack of diversity and collective blindness challenge the opportunity for diverse ideas to surface. These challenges could, according to Syed, be one of the many drivers for the intelligence failures preceding the September 11, 2001, attacks in the United States.7 In Denmark, there is a tendency to recruit similar civil analysts from the same academic backgrounds, which, in a worst-case scenario, could lead to collective blindness with potentially tragic outcomes.

Data direct, support, and assist policing decisions at all levels in the organization. Denmark has, in the last decade, invested heavily in IT solutions and created a robust and innovative data-driven platform from which it is possible to integrate numerous data sources. In general, this platform is capable of supporting analysts’ efforts to create a richer and more robust depiction of the criminal environment. Data, including data-quality and IT systems, are without a doubt the backbone of modern analysis. But as systems get more complicated and data turn into “big data,” the need for artificial intelligence and machine learning increases and the collection methodology becomes multifaceted and even more complicated. Therefore, it is important to be specific as to what data are collected and to analyze and to continuously focus toward supporting analysts.

Data direct, support, and assist policing decisions at all levels in the organization. Denmark has, in the last decade, invested heavily in IT solutions and created a robust and innovative data-driven platform from which it is possible to integrate numerous data sources. In general, this platform is capable of supporting analysts’ efforts to create a richer and more robust depiction of the criminal environment. Data, including data-quality and IT systems, are without a doubt the backbone of modern analysis. But as systems get more complicated and data turn into “big data,” the need for artificial intelligence and machine learning increases and the collection methodology becomes multifaceted and even more complicated. Therefore, it is important to be specific as to what data are collected and to analyze and to continuously focus toward supporting analysts.

Olesen points out.

In the past years, we’ve come far when it comes to incorporating analysis into the way the organization works. We don’t want to spend time creating fancy analysis reports for the chief inspectors’ desks drawers …we make sure that the topic we look into is specifically requested from management and that we can operationalize what we learn and thus make a tangible and positive change for our colleagues in the field.

The Value of Investing in Analysts

A more complex criminal environment creates an ongoing demand for smarter solutions. To ensure the success of new technologies, the Danish police decided to focus and invest in the analysts behind the computers. This led the National Center of investigation (NCI), to establish a specific ILP project with a particular focus on supporting the analytical capabilities within the Danish Police. This project was taken over in 2022 by the new national unit—The Special Crime Unit (SCU).

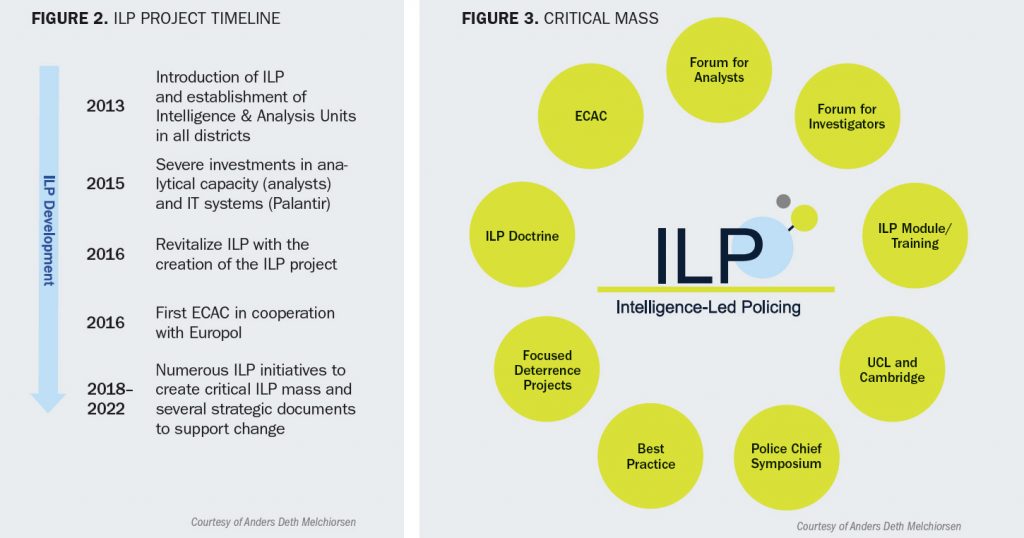

However, the Danish ILP and data-driven journey initially began as early as 2007 succeeding into 2013 with the formation of Intelligence and Analysis Units (EAE) in all 12 police districts, which later led to the ongoing 2016 ILP project.

Creating a Data-Driven ILP Critical Mass

So how does an agency create a critical mass to strengthen its analytical capacity and enhance the decision-making platform? The answer was not straightforward, but based on multiple evaluations within the organization, the Danish National Police launched several initiatives (see Figure 3).

ILP Forums

One of the first essential initiatives in Denmark has been the Forum for Analysts (FFA), a regular gathering of all police analysts. The forum is designed for like-minded people with similar interests and professional backgrounds, where new techniques are brought to the table both in plenary sessions and in topic-specific breakout sessions. It is also a forum where management gets the opportunity to present the strategic direction, mission, and vision for the organization.

“Collaboration with colleagues from beyond Denmark has also enhanced the country’s analytical capacities, through the sharing of ideas from near and far.”

Through the forums, ILP, analysis, and the data-driven enterprise have emerged from being something solely discussed internally in the analysis hubs to a proactive force. For example, in September 2022, two patrol officers presented their analysis of cooperation between the analysts and patrol officers in the western police district of Copenhagen at the seventh FFA. Their analysis demonstrated how district analysts can successfully reach frontline patrol officers and create a close and rewarding cooperative relationship between real-time policing and analysis. The example also illustrates the obvious changes within the organization, with analysis moving from “silo specific” to a more general understanding and interest in the analysis work across the organization.

Following the FFA, it was decided to establish a Forum for Investigators (FFI). It shares the same overall goals of bringing together peers and enabling discussions and experiences with respect to current trends and techniques. It is, however, also designed to systematically familiarize investigators with ILP and instigate a more data-driven approach to investigations. In the wake of this initiative, it has been decided to create a third specific ILP forum—the Forum for Leaders (FFL)—to help managers within the decision-making framework discuss and get familiarized with the decision maker’s role within the ILP realm.

Simultaneously, ILP was formally adopted in 2018 with the introduction of the Intelligence & Analysis Doctrine. This doctrine, in simple words, sets the standard of how to work smarter and more intelligence led, with a specific focus on how analysis and being a data-driven enterprise can support and strengthen policing in Denmark.

Training Programs

The University College London (UCL) skills development program was a designated training program carried out by UCL in order to strengthen the analytical skills in criminal intelligence and crime analysis between 2018 and 2019 in Denmark. The program was designed to improve analytical techniques, analysis theory, and the use of analysis outputs for informing police interventions and investigations. Additionally (but outside the ILP project), the Danish police academy engaged in close cooperation with the Danish Tryg Foundation that made it possible to enroll a high number of analysts from Danish police into the Police Executive Programme in applied criminology and police management at Cambridge University, UK. These collaborations with respected academic institutions have been essential in advancing the intellectual capacity of data-driven policing within Denmark.

International Conference

Collaboration with colleagues from beyond Denmark has also enhanced the country’s analytical capacities, through the sharing of ideas from near and far. In 2016, the Danish police hosted the first European Crime Analysis Conference (ECAC) in cooperation with Europol. This conference has become an important platform for analysts from around the world to share best practices, network, and engage in essential cross-border discussions on key questions in analysis. In 2020, just before COVID-19 closed down the world, more than 350 analysts and decision makers from more than 40 countries participated.

The next annual gathering is scheduled in Denmark on May 31–June 1, 2023. Special Crime Unit Deputy Commissioner Mikael Wern stated,

To ensure that the competencies of analysts from Danish police meet the analytical standard around the world, including new research within criminal analysis and criminal intelligence, ECAC is an essential platform.8

|

United Against Violence Following ECAC 2020 and a presentation by David Kennedy from the National Network for Safe Communities (NNSC), USA, on different focused deterrence projects, the Danish police and Copenhagen police initiated a collaboration with NNSC called United Against Violence, an ongoing project to combat group violence in Denmark. As Copenhagen Analyst Olesen states: In order to combat group violence in Copenhagen, upper management decided to implement a strategy called group violence intervention (GVI), a research- and evidence-based approach. By enhancing our working relationships both internally and externally and changing how we think of communication with the group members within the framework of GVI, we expect to reduce the amount of serious violence among group members. |

Additional ILP initiatives have been carried out, as shown in Figure 3, such as internal training and ILP management courses, but to highlight the initial objective and ultimately the main goal of the ILP project, the greatest value in supporting the analytical capacity in Denmark has been found in introducing diverse training, seminar, and conference opportunities as has been done since 2016 and will continue into the future.

It is only fair to emphasize that the above mentioned ILP initiatives should be seen in conjunction with other local and national ILP initiatives. Additionally, the LIP project should not be seen as the sole driver for change in Danish police, the project succeeded in creating a “climate of change” and opened the way for other evidence-based and knowledge-driven initiatives.

The Future of ILP and Data-Driven Policing

The complexity of crime, the overwhelming influx of reported IT-related crimes, and the birth of new criminal activities such as IT-related eco-crime, environmental crime, and cybercrime call for new methods and approaches. These inevitably pave the way for paradigms such as ILP and data-driven policing, as traditional policing methods rarely correspond with the complexity found in 2023.

This new reality also calls for decision makers at all levels to continue to engage in close collaboration with the analysis function, and, as Ratcliffe points out, this relationship underpins the leaders’ ability to be able “to understand and be educated in crime analysis and intelligence-led policing.”9 The Danish police have come far since the initial thoughts on ILP. Denmark is in a unique and privileged position to have the capacity to be one of the forerunners within the intelligence-led, evidence-based, and data-driven domain.

However, nothing comes without risks, and Denmark’s fortunate position needs to be closely managed, directed, and supported. The lack of genuine cooperation between policing and academia is also something that needs to be reviewed, however. Nonetheless, while the journey may be long and bumpy, with a bit of luck, perseverance, and determination, ILP can be further consolidated in Denmark as the underpinning approach to crime detection, prevention, and deterrence. 🛡

Notes:

1Jerry H. Ratcliffe, Intelligence-Led Policing, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2016); Nick Tilley, “Modern Approaches to Policing: Community, Problem-Oriented and Intelligence-Led,” in Handbook of Policing, ed. Tim Newburn (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2008); Morgan Burcher and Chad Whelan, “Intelligence-Led Policing in Practice: Reflections From Intelligence Analysts,” Police Quarterly 22, no. 2 (June 2019): 139–160; Jeremy Carter and Scott Phillips, “Intelligence-Led Policing and Forces of Organisational Change in the USA,” Policing & Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy 25, no. 4 (2015): 333–357; Adrian James, Understanding Police Work (Bristol University Press, 2016).

2Ratcliffe, Intelligence-Led Policing, 81.

3Ratcliffe, Intelligence-Led Policing, 66.

4Michael S. Scott and Stuart Kirby, Implementing POP, Leading, Structuring, and Managing a Problem-Oriented Police Agency (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing, 2012).

5Eric Halford, November 28, 2022, comment on Jakob Lindergaard-Bentzen’s LinkedIn profile.

6Maja Bisgaard Olesen (analyst, Copenhagen Police), email, November 20, 2022.

7Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking (London, UK: John Murray Press, 2019).

8Mikael Wern (deputy commissioner, Special Crime Unit), email, November 10, 2022.

9Ratcliffe, Intelligence-Led Policing, 82.

Please cite as

Jakob Lindergård-Bentzen, “Preventing, Disrupting & Deterring Crime with Data: Intelligence-Led Policing in the Special Crime Unit in Denmark,” Police Chief 90, no. 4 (April 2023): 48–52.