Individuals planning violent acts engage in observable behaviors. They may gather information through research and reconnoitering, boast of their nefarious intentions in person or online, collect weapons or other materials to facilitate their plans, or start acting suspiciously or out of character. They may obsess on some perceived inequity, often abruptly or seemingly out of the blue. A sudden loss of employment, spouse, or living arrangements may prompt unusual activities. Often, they say their goodbyes or give away cherished possessions. In whatever way a specific individual intending violence behaves, learning about that individual’s behaviors—recognizing the potential violence that may occur and then taking the best steps to thwart that intention—presents one of the greatest challenges to today’s law enforcement.

Threat management requires detecting, then defusing any risk of violence. Therein lies the rub: defusing pivots on detecting. Forestalling first requires finding. Establishing an effective process for identifying individuals intending violence constitutes a primary challenge for today’s law enforcement. Potential violence cannot be deflected if those involved in law enforcement threat management programs–the threat assessors–do not first recognize the likelihood of a violent outcome. Recognition is the first step; without identifying the possible source of the violence, threat assessors cannot assess, much less defuse, any situation. What—or where—are the so-called red flags that seem so readily apparent after the violence occurs? In short, what need threat assessors detect?

This article is for those in law enforcement providing protection through threat management, the process for actually preventing targeted acts of violence. That protection may extend to citizens, courthouses, schools, businesses, houses of worship, or other entities falling under police jurisdiction. No matter the possible prey, threat assessors must first pinpoint the source of the hazard. Doing so requires recognizing those who bear some disgruntlement or discontent toward the target or what the target may symbolize. Those who seek resolution through violence comprise the most concerning subjects. Subjects of concern express their intentions in noticeable ways. Detecting violent intent, then, depends on an efficient and timely process for spotting those who feel wronged enough to take action.

Set forth herein are universal criteria threat assessors can be used in uncovering the risk of violence. By “universal,” the authors do not mean definitive or all inclusive. Rather, this definition of possible indicators of impending violence consists of representative pointers described at a general level. Each set of circumstances, each clue, is entirely situation dependent. They must be assessed within the setting in which they occur. Consequently, the threat assessor must evaluate every threshold within the overall context of what is happening at the time of the assessment. Broad guidelines only, not a detailed blueprint follow. But the authors believe that this guidance bears within it the best hope law enforcement has for detecting potential violence.

The Threat Management Process

Three sequential steps comprise the threat management process. First, the threat assessor identifies a subject of concern based on the individual’s problem behavior. Next, the assessor assesses the subject, the situation, and the circumstances to determine the level of risk at this time. Finally, the threat assessor recommends the best strategy to manage the subject away from violence. Of the three steps, identifying the subject is a one-off; that is, once identified as a potential risk of violence toward the target, the subject need not be identified again. The subject stays of concern for as long as the potential for violence obtains. Conversely, assessing and managing the subject are ongoing processes, with new assessments and new strategies conducted and selected as the assessor receives new information or the situation and circumstances change.

Yet, even though a one-off, identifying subjects who present potential risks of violence toward a target give the threat assessor a daunting challenge. Learning about threatening, suspicious, or inappropriate activities around any target requires accepting that reports of such behaviors may indicate future violence. Open lines of communication with those best positioned to observe or become aware of any such untoward activities offers the only recourse. But those lines must first span the gap between potential reporters and those trained to act on the information. Bridging that abyss depends on training, retraining, and training again until identifying and reporting violence indicating behaviors or situations become deeply ingrained in everyone involved. Robust systems and information portals must also be in place to ensure information moves to the right person, whether it is reported on a Wednesday at noon or Sunday at midnight.

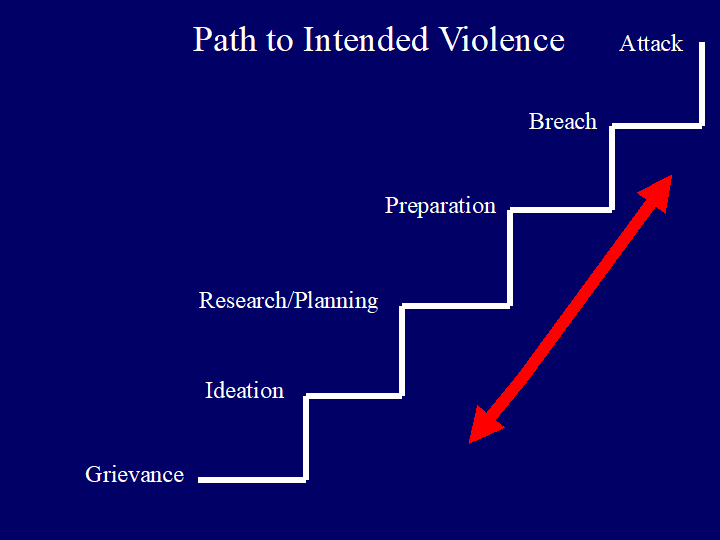

The authors’ approach to identifying potentially violent subjects draws on a foundational concept in threat management: the path to intended violence. The path consists of the various steps or activities an individual contemplating a violent act must take in order to consummate that violence. First, the subject develops a grievance motivating the potential violence. From grievance, the subject next develops the idea that violence alone can resolve their problem. Ideation then leads to research and planning during which the subject explores how to make the assault. Research and planning, in turn, leads to preparations, i.e., the subject puts together the materials needed to enact the plan. Once prepared, the subject must next breach the target’s security. From that point, the subject must finally attack. In general, then, all acts of intended violence move along a path, the milestones of which are grievance, ideation, research and planning, preparation, breach, and attack. Figure 1 illustrates this path.

|

Activities related to each point along the path hold the best promise for identifying subjects intending a violent act. That is to say, recognizing that a subject of concern engaged in behaviors related to research and planning or preparation, for example, strongly suggests that the subject has stepped further along the path to intended violence. Subjects of concern who make suspicious inquiries into the target’s habits or routines, or who coincidently purchase a firearm, or who suddenly spend time seeking or obtaining explosive components warrant inquiries, if not necessarily a full-fledged law enforcement investigation. These and comparable activities do not prove violent intent, but they certainly suggest the possibility. Nor do they constitute criminal acts supportive of prosecution. Messages addressed to—or clearly about—the target indicating that the subject entertains inappropriate feelings or intentions surely justify law enforcement’s attention. Ignoring that potential may be at the target’s expense.

Activities suggestive of path-like conduct need not be criminal in nature. Indeed, most of these behaviors fall well within the law while still portending evil intent. Threat assessors do not punish law violations so much as prevent them. They do not wait until a crime occurs. The threat assessor’s primary task is to divert malevolent intentions from becoming actions. Shooting at a firing range may be perfectly legal and innocent, but when it occurs within a context of other activities indicating some deeply held grudge against the target, target practice takes on a different hue. At a minimum, such behavior by a subject of concern prompts the threat assessor to find out more about what may be going on vis-à-vis the subject and the target. Put bluntly, firing at a bullseye differs entirely from shooting a photograph of the target.

The first challenge confronting threat assessors requires establishing a process whereby individuals, including police officers, who become aware of activities indicative of path-like behaviors know to report their suspicions to the appropriate unit or agency. The authors herein offer a universal framework for identifying the types of inappropriate behaviors, situations, communications, or contacts that need reporting. The criteria cross target venues: that is, they apply regardless of the social setting in which the inappropriate behavior or contact occurs. The reporting types apply equally to targeted domestic violence; school violence; assaults on public figures and facilities; and attacks on symbolic targets such as houses of worship, public monuments, or other settings that stand for something. The authors offer the criteria as an instructional tool to train law enforcement officers and other appropriate audiences in what to report and why.

Fundamentals of an Effective Threat Management Process

The basic building blocks of any effective threat management process consist of what the authors call its DRA. In establishing a threat management process, whether for people, places, entities, or processes, the threat assessor must take care that the approach includes ways to Detect subjects traveling on the path to intended violence, methods by which those detections can be readily Reported, and a system ensuring that the reports are promptly reviewed and Acted on.

Detecting subjects embarked on the path to intended violence depends on establishing lines of communication alerting law enforcement to any behaviors suggesting the subject is moving along the path. Unfortunately, current practice does not usually focus on training the people who need the training the most, largely because they seem hidden in plain sight. In school settings, those who need instruction on what to report are not just the teachers and administrators, but also the cafeteria workers, bus drivers, groundskeepers, and crossing guards. That is, it is the groups that mingle most with the students. They are best positioned to pick up on the scuttlebutt or to observe suspicious behaviors. At workplaces such as a courthouse or city hall, they are not just the managers and executives, but also the support staff, maintenance workers, delivery people, IT staff, and anyone else who works with the public or other employees. In a word, individuals most likely to detect inappropriate activities are those most immersed in day-to-day operations, that is, the ones who reside within the hustle and bustle.

Training the right people in what to detect makes little sense if those individuals have no means or opportunity for reporting what they notice. That is why the second building block is an effective reporting process. The law enforcement executive should advocate procedures, means, and methods for passing information efficiently and smoothly to the threat management team. That team, in turn, should be competently trained in obtaining, prioritizing, and evaluating everything that gets reported. The process, too, should ensure that the reports are received in real time, regardless of what time or day it occurs. This cannot be a nine-to-five job, but, rather, must be operational day or night.

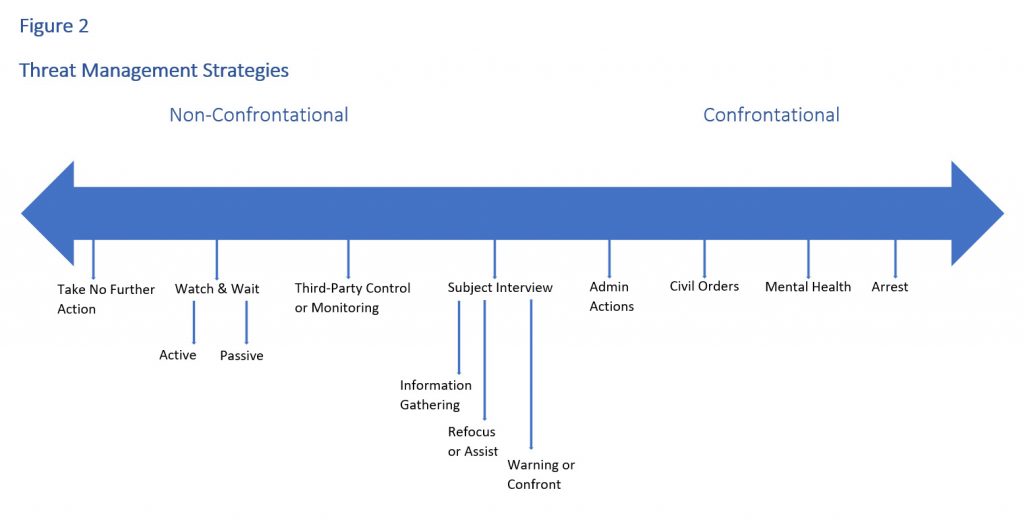

Detecting and reporting, of course, are worthless without trained individuals capable of assessing and acting on the reports. By acting, the authors do not necessarily mean responding to each report as though to a five-alarm fire. Rather, the response may range across the gamut of threat management strategies, from taking no further action at this time in response to low-risk situations all the way to invoking law enforcement responses to imminent threats. Figure 2 shows the range of management approaches available.

All Threat—All Target Reporting Criteria

The point is that the process needs to prompt a proportionate response even if the response is deciding not to act at this time. That decision—to take no further action at this time—is itself an action. Acting also includes notifying related potential targets and jurisdictions that share any possible risk. Not acting is not a strategy.

Guidelines follow for the type of evidence or clues threat managers should have reported to them. In the past, such criteria focused on what organizations identified as their most valuable or vulnerable assets, such as executive officers or the facility. Previous criteria also assumed that threats most likely came from an outsider or the individuals served by the organization, such as students, customers, or constituents. The criteria below take a 360-degree approach without any underlying assumptions other than that risks can rarely be predetermined.

In addition to law enforcement personnel, distributing the criteria below as widely as possible within the venue concerned is recommended. At municipal government facilities, for example, the list should be posted prominently wherever employees gather and should be used frequently in employee orientations and training sessions. Associates of public figures should become familiar with them, as well as school employees and those employed at facilities open to the public. These criteria can also be presented during crime prevention training to vulnerable organizations such as houses of worship, medical facilities, and schools. Table 1 is a typical example of the ALL THREAT—ALL REPORTING CRITERIA as it might be distributed or displayed to those most likely to witness reportable behaviors.

The reporting criteria begin with two fundamental applications:

- The focus is on observable behaviors.

- The suspicious behaviors are associated with an identifiable target or type of target.

The reporting criteria explicitly omit unfounded speculations, idle suspicions, or other baseless or unobserved accusations. Its focus is behavior, not a profile or individual typology. Rather, the reports must be fully grounded in actual, observed, or reported behaviors. Threat assessors risk wasting their time pursuing unfounded rumors or spiteful allegations. Instead, the assessor should always focus on actual events, on what happened, not on what someone fears may occur.

The criteria are threshold indicators that need reporting. They are the beginning of a process. Envision placing a large funnel through which information is channeled to a central location. Standing alone, any single criterion may mean nothing; however, when joined with other reports, environmental circumstances, or the outcomes of further inquiry, they may reveal actionable threat information. The point is consistent and broad-based gathering of pertinent information is fundamental to the safety of organizations and individuals. Ignorance is not bliss in today’s threat environment.

Please cite as

Stephen W. Weston and Frederick S. Calhoun, “Reporting Criteria for Detecting Violent Intent,” Police Chief Online, January 26, 2022.