Law enforcement and the communities they serve want many of the same things. They want effective responses to crime and other problems.

They want policing that promotes safety and trust. And they want alternative responses for behavioral and social problems to safely connect people to services that address root causes of behavior while allowing law enforcement to focus on solving and preventing violent and serious crime. While individual police departments and other community organizations have begun implementing alternative responder programs, there is no common understanding of how many communities are doing so, what those programs are, how they work, or what their benefits and challenges may be. The University of North Carolina School of Government Criminal Justice Innovation Lab (Lab) partnered with the North Carolina Association of Chiefs of Police (NCACP) to address that knowledge gap. The project team included seven police chiefs, a deputy chief, and a Lab research team. Through a survey of NCACP members, follow-up interviews, and case studies of four departments, the project team obtained information about existing and planned-for alternative responder programs in North Carolina and recommendations from communities engaged in this work.

Key Findings

NCACP members from 142 police departments responded to the project survey—a 68 percent response rate. The research team interviewed staff associated with nine departments to learn more about their programs. The team spoke with police chiefs, assistant and deputy chiefs, majors, sworn officers, a community care liaison, a psychologist, a social worker, and an academic director. The team also executed case studies of the programs at four of these police departments. All four sites had between 100 and 150 officers and served jurisdictions with populations of 44,000 to 71,000 people. The selection of the four sites was intentional based on data showing that 97 percent of U.S. police departments serve less than 100,000 people. This work provided rich information, including the following key findings.

Program Types

The project team found that alternative responder programs can take multiple forms. Such programs include police department-based models, like crisis intervention teams; homeless outreach programs; and case management programs, where specially trained police department staff respond to crisis calls and/or follow up with individuals in crisis. Alternative responder programs also include community-based programs, like mobile teams of mental health, disability, or social services staff that respond to calls alone or in partnership with medical professionals. Programs also can involve a co-responder team, where mental health, substance use, or social services staff respond with law enforcement to calls for services. However, the research revealed that programs are not easily categorized. Some co-responder programs, for example, are housed in police departments, while others are housed in community organizations. Similarly, police departments reported that some programs—like homeless outreach programs—can be either police department based or community based.

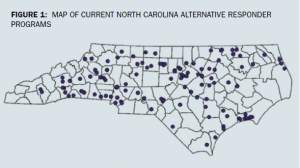

The research showed that police departments and community organizations across North Carolina have implemented and are interested in a variety of alternative responder programs. Of the 142 police departments that responded to the survey, 83 percent reported having at least one alternative responder program, either housed in the police department or at another community organization. Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of current programs in North Carolina. Notably, programs are reported throughout the state, in rural, suburban, and urban communities.

The research showed that police departments and community organizations across North Carolina have implemented and are interested in a variety of alternative responder programs. Of the 142 police departments that responded to the survey, 83 percent reported having at least one alternative responder program, either housed in the police department or at another community organization. Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of current programs in North Carolina. Notably, programs are reported throughout the state, in rural, suburban, and urban communities.

Survey results showed that mobile crisis programs are the most common type of existing programs. Results also revealed that interest is high in creating new programs—over one-third of police departments reported that they are considering a new alternative responder program. The greatest interest for the future is in mental health co-responder programs. Figure 2 shows the frequency of current and considered alternative responder programs.

While some programs are relatively new, others have long track records. Although widespread attention on alternative responder programs is new, survey results showed that some North Carolina programs—like community-based homeless outreach programs—have been around for decades.

Existing programs use varied staffing strategies. Police departments reported that programs are staffed by a variety of professionals, including mental health specialists, substance use treatment providers, social workers, paramedics and EMS, and peer support specialists. Staff can be embedded within police departments or at a partner organization.

The study also found variation in how partners collaborate to implement alternative responder programs. Collaboration can include, for example, departments providing direct and indirect referrals, receiving backup support during calls, and supporting program development.

Program Benefits and Outcomes

Police department staff and partners reported a range of program benefits, including promoting community trust; connecting community members to services to address the root causes of behaviors; reducing repeat calls for service and officer use of force; improving efficiency and effectiveness of law enforcement resources, including freeing up officers to focus on pressing public safety matters; freeing up jail space; and promoting court appearances. One surprising program benefit reported was officer wellness. Alternative responder programs alleviate some of the pressures police officers face when dealing with complex issues like mental health crises and homelessness. Such collaborations also facilitate relationships so that police officers know where to turn for counseling services for themselves or others.

The research revealed cross-cutting factors for positive program outcomes: program integration and local service availability. In interviews, department and program staff noted that for police-based and co-responder programs, integration within the department is a key factor for success. However, staff reported that limited services and resources, like housing and behavioral health services, constrain programs’ potential to address the root causes of behaviors and interrupt the cycle of repeat crisis calls.

Recommendations

Staff interviewed at the four case study sites offered the following recommendations for other police departments considering establishing an alternative responder program.

1. Start by assessing community needs and resources. Staff from all four police departments recommended starting with an assessment of local needs and resources. Staff emphasized that what works in one community might not work

in another, and identifying local needs and resources is a critical first step. One department recommended looking at calls for service, meeting with community organizations to understand the needs they serve, and asking officers what issues they see in the field. Another recommended starting data collection early to assess needs and lay the foundation for program evaluation, identifying the types and number of calls the new program would target. Staff also advised coordinating with other organizations like service providers, the local jail, the prosecutor’s office, and pretrial release programs; these entities may have relevant data or be able to identify target populations and outcomes to monitor. Understanding these needs will help the department assess the expertise and licensure needed by program staff. They also recommend identifying potential partner organizations and resources those organizations can offer.

2. Select program staff intentionally. Police department staff recommended selecting program staff to align with department culture to promote strong partnerships between police officers and non-police program staff. They also suggested selecting crisis responders with diverse professional backgrounds to broaden the department’s crisis response skillset and help responders meet a variety of needs. Finally, staff recommended selecting team members with experience working with the community, as well as with the patience, compassion, and persistence needed to engage with people experiencing crises.

3. Scale over time. Staff noted that departments cannot address every problem at once and that it is often best to start small with a pilot program or a single staff member. They noted that starting with a time-limited or smaller program allows the department to learn from experience and refine implementation.

4. Have strong leadership. Staff from one case study department noted that leadership must convey support for the program and that if crisis response is not a leadership priority, it will be difficult to build officer buy-in. Interviewees from another department emphasized that there should be a department point person for program staff to contact with problems and that because of staff turnover in the department and in partner organizations, departments need to plan for program sustainability.

5. Build officer buy-in. Staff recommended building support for the alternative responder program by helping officers understand that crisis response frees them up to do the law enforcement functions for which they are trained. Interviewees also suggested intentionally incorporating crisis response into the department’s structure and culture so that services are visible to officers.

6. Identify funding sources. Police departments need funding both to start programs and to sustain them. In some cases, partner organizations may be able to support the program, but at least one case study department recommended identifying other funding sources.

7. Monitor and adapt over time. Staff at one case study site noted that adapting and iterating on the program over time can help build out from strengths and realize additional program benefits that may not have been envisioned initially. Staff from another department that participated in interviews echoed this view, stating that departments should start with local needs and adjust as needed. They noted, “No matter what model you go with, it’s a living, breathing model, and it will evolve to what you need it to be.”

8. Do not be afraid to try something new. One case study department noted that implementing a program requires a new approach to law enforcement. While there may be an initial adjustment period, they encourage police departments to be open to learning how to use new resources.d

Please cite as

Jessica Smith and Maggie Bailey, “Alternative Response Models and Outcomes,” Research in Brief, Police Chief 91, no. 2 (February 2024): 26–29.