The mental well-being of the men and women who serve and protect communities across the world is every bit as important as their physical health and safety. Unaddressed mental health issues can take a toll on officers. Police employees are regularly exposed to appalling things that the majority of society are fortunate enough not to witness or experience. As a result, many officers will suffer a mental health injury—and most will do so in silence.

More recently the focus on police well-being, rightly so, has focused on the alarming escalation rate of suicide deaths among those serving in the profession. Programs and intervention strategies have focused on the aspect of the mental health spectrum where officers have already suffered an injury and require intervention and treatments. However, questions still remain. Why do law enforcement officers continue to have high rates of mental illness and suicide? Why does the stigma of experiencing a mental health issue still strongly permeate policing organizations? Why do police personnel remain reluctant to come forward and seek help?

The answers potentially lie in more broader issues that externally impact police outside the influence of trauma exposure. A combination of external life stressors, organizational pressures, dysfunctional leadership practices, and cultural impediments cumulatively build tension, aggravation, and frustration. When these issues intersect with trauma exposure, the effect on the individual can be substantial to the point where it permeates the officer’s functional wellness, organization, and loved ones.

Understanding the Whole Picture

Mental disorders throughout the world are on the rise and will cost the global economy approximately $16 trillion (USD) by 2030. An estimated 12 billion working days are lost every year because of mental health injuries.1

A 2017 study conducted by researchers at the University of Toronto, Canada, demonstrated the dangers of failing to acknowledge and deal with mental health among police. Researchers’ interviews found that first responders with mental health injuries exhibited “performance deficits on complex cognitive tasks,” which could include tasks that required first responders to assess risks, plan multistep responses to an emergency, or execute complex operations where there are multiple offenders and or victims.2 The risk to society is high if these health issues are not dealt with appropriately.

A 2018 Cambridge University study of police in the UK revealed that two-thirds of all respondents said they had a mental health issue directly resulting from police work. Yet almost all the survey’s respondents—some 93 percent—said they would go to work as usual if suffering from psychological issues such as stress or depression. They would do so without seeking treatment due to the associated negative organizational stress and impacts.3

As experienced police know, often the public perceive police to be something other than human, expected to accept and tolerate things well beyond that of anyone else in society. Police wear a veneer of being unbreakable, of being a rock for everyone, to the extent that they forget to take care of themselves.

What other profession requires one to deal with the worst of human nature? What other job requires an individual to be in a constant state of hypervigilance and alertness, yet at the same time being a counsellor, a social worker, a medic, a lawyer, or a prison warden? What other profession authorizes someone to take another person’s liberty or, at worst, execute deadly force on another human being, but then mandates that one renders assistances to the person who has just tried to harm or kill him or her? What job causes people to wonder whether they will come home to their loved ones at the end of each day?

From the time new recruits enter the academy, they are taught elements of the law, internal procedures, protocols, drill, physical self-defense, and emergency driving. They are prepared and trained to use batons, capsicum spray, and handcuffs and taught when and how to use lethal force. Recruits are brought to the peak of physical fitness, educated in how to maintain neutrality with their emotions, and taught to remain composed and calm in situations where others would not.

What many new officers are not educated on is how to look after their mental health and the substantial impact it might have on them, their careers, and their families.

Mental Health Leadership in Policing

Leadership is a pivotal element of the police institution across all levels. Leaders have a moral responsibility to ensure the health and safety of those they supervise; in most countries, they also have a legal responsibility to do so under occupational health and safety regulations.

Leaders play a key role in supporting the mental health of those they supervise and are well positioned to identify the early signs and symptoms of a worker who may be struggling with his or her mental health and to facilitate improvement and recovery.

Irrespective of rank, position, role, or function, internal and external stressors in policing can be just as damaging to members as traumatic experiences and can induce a negative psychological response:4

-

- External stressors – jurisdictional isolation, seemingly ineffective legal and court systems, adverse media accounts, impact of negative and venomous social media

- Internal stressors – poor supervision and leadership, lack of career development opportunities, inadequate reward system, unpleasant policies, over-reporting requirements, mountains of paperwork and budgetary constraints

- Performance stressors – role ambiguity and conflict, adverse work and roster schedules, inherent fear and danger, sense of uselessness, and absence of closure

- Individual stressors – feeling overcome by fear and danger, pressures to conform, gender disparity, bullying, sexual harassment, ethnicity and cultural differences, lack of understanding of topics such as LGBQTI

- Life-threatening stressors – ever-present potential for injury or death to the individual, fellow police, or members of the public

- Social isolation stressors – cynicism, isolation, and alienation from the community; prejudice and discrimination

- Organizational stressors – administrative philosophy, changing of policies and procedures, morale, job satisfaction, and misdirected performance measures

- Functional stressors – role conflict or confusion, use of discretion, and legal mandates and obligations

- Personal stressors – home life stressors, including personal issues, spousal issues, illness, problems with children and aging parents, marital distress, and financial constraints

- Physiological stressors – fatigue, medical conditions, comorbid health issues, poor sleep, poor nutrition

- Psychological stressors – all the preceding and the exposure to shocking situations

As a police leader, mental health can seem obscure, subjective, and messy to engage in; uncomfortable; complex; and, at times, highly threatening, hence the reluctance for many organizations and individuals to involve themselves.

Books, articles, podcasts, and blogs on nearly every aspect of leadership crowd the management section in bookstores and online portals. There are abundant Ted Talks, webinars, and conference material that detail at length how to lead in today’s society, yet hardly any of these publications deal with the capacity of leaders to lead, understand, support, and drive better mental health in the workplace.

Leadership plays an unconditional and fundamental role in creating the type of environment that promotes mental and emotional well-being and in making it safe to discuss and seek help in the workplace. Moreover, leaders have the capability to initiate the social, physical, and policy environments within the workplace can all influence the ability or probability of individuals engaging in a better mental health program, plus they can establish and foster an environment conducive to accepting and destigmatizing mental health injuries.

Leaders are in the best position to both identify mental health issues in workers and to respond to them in appropriate, meaningful ways. To engender trust and confidence of their staff, it is important that leaders possess a basic understanding of mental health presentations, symptoms, and behaviors that may identify potential mental injuries that allow for early intervention strategies to be deployed, just as they would be for a physical injury.

Specifically, leaders need to have an awareness of the variety of trauma and operational stress issues that regularly confront police, including the following:

-

- Acute trauma – often associated with a single event that happens in one’s life.

- Cumulative trauma – adversity as indexed by a count of lifetime exposure to a wide array of potentially traumatic events.

- Compassion fatigue – a condition characterized by a gradual lessening of compassion over time, common among workers who work directly with victims of trauma.

- Vicarious trauma – a normal response to the ongoing exposure to other people’s trauma, often developed by those working to support people who have experienced trauma, and hearing, seeing and learning about their experiences.

- Operational stress injury – any persistent psychological difficulty resulting from operational duties.

- Burnout – the harmful physical and emotional responses that occur when the requirements of the job do not match the capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker.

- Moral injury – the psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual aspects of trauma. Moral injury is a normal human response to an abnormal traumatic event where police have witnessed or been involved in matters that transgressed their deeply held moral beliefs and expectations. Moral injury can also be experienced by police who have been transgressed against in the workplace. The injury may in those cases include a sense of betrayal and anger. Those who have seen and experienced death, mayhem, destruction, and violence and have had their worldviews shattered experience moral injuries.5

There is very little in police education that prepares a leader for how to respond when a team member confides to them that they’re struggling with depression, anxiety, suicidal ideations, or an operational stress injury.

As a leader seeking to engender understanding and support for wellness in policing, authenticity is the greatest asset. If police leaders can recognize the signs and symptoms; discuss mental health openly without bias; know the resources available to workers, both within and outside the workplace; and support and guide those with mental health injuries through their recovery journeys, they can establish trust, reduce stigma, and normalize the understanding of mental health in the workplace.

The Impact of Police Culture on Mental Health

Police culture is a pervasive microcosm in which a closed mini-society perpetuates a sense of strong cohesion, a code of behavior, and dependence upon one another for survival. It contains a series of assumptions, beliefs, expectations, and philosophies that governs the profession’s interactions, performance, and roles. It informs police on how to go about their tasks, how hard to work, what kinds of relationships to have with their fellow officers and other categories of people with whom they interact, and how they should feel about police executives, judges, laws, and the requirements and restrictions they pose. Most significantly, the traditional policing culture values strength, fearlessness, integrity, stoicism, distrust, self-reliance, and controlled demeanors and emotions.

“Leadership plays an unconditional and fundamental role in creating the type of environment that promotes mental and emotional well-being.”

Workplace culture can have negative effects on mental health and well-being. A stigma associated with mental health conditions is still prevalent among first responders. Many people worry about talking about suicide or mental health conditions with someone who seems to be struggling because they are afraid of doing harm or saying the wrong thing. Also, in many first responder organizations, there are concerns about the confidentiality of support services, and workers sometimes fear that accessing these services may influence how management sees or treats them. These concerns may discourage workers from seeking help and are significant barriers to promoting mental health.

As a cop, there is an awful sense of having “lost control” by needing to ask someone else to help fix the problem, especially since officers are perceived by the community to be stoic, strong, unflappable, and unshakable.

Few police officers have trouble asking to go home due to a migraine or the flu. But when it comes to talking about having a mental health condition, police officers are hesitant to broach the topic with family, friends, and colleagues, let alone with those in charge of their careers. It is widely perceived within the police culture that acknowledging a mental health injury is a sign of weakness or a career killer and places individuals into a stereotypical group that consequently leads to discrimination, isolation, and alienation. Fearful of being perceived as weak and untrustworthy or suffering potential sanctions or loss of professional opportunities, officers are therefore unlikely to reach out and seek help, even privately.

Institutional Strength and Capacity through the Socio-Ecological Prism

Mental wellness issues are difficult to address; these are problems the police profession has not dealt with well in the past. The liability and risk to organizations are problematic, which promotes a risk-adverse response when dealing with mental health claims. Moreover, the topic possesses many gray areas and decisions about how to deal with mental wellness issues can be highly subjective.

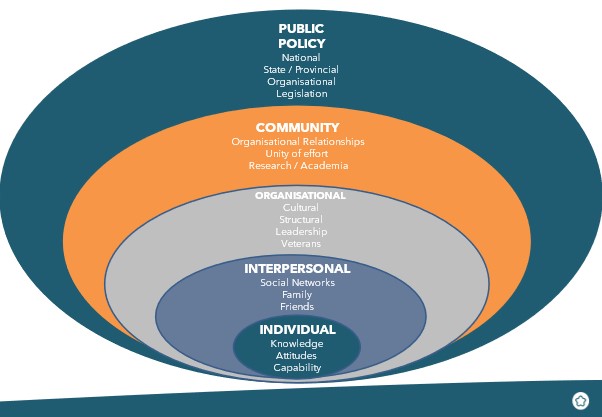

Fusing leadership, culture, and institutional strengthening through a socio-ecological model (see Figure 1) will advance the understanding of the dynamic interrelations among police personal and environmental factors that can support a better organizational mental health approach. The factors and behaviors that impact on an officer’s mental health are broad, complicated, and diverse. Developing and implementing a wellness program is not a generic endeavor. Agencies must tailor their wellness initiatives to meet their specific social, cultural, and department needs through an innovative programming approach that is multifaceted, inclusive, and holistic. Agency leaders should consider other important related topics, such as promoting individual financial health, improving nutrition, advancing sleep hygiene, and extending support to family and retired members. Of paramount significance is appealing to the hearts and minds of staff, emphasizing that their health and well-being is of utmost importance. The ultimate goal is to prevent police from contracting a mental health injury in the first place.

| Figure 1: Socio-ecological Model |

|---|

|

The socio-ecological framework can be an ideal tool for addressing these broad issues and implementing new mental health programs through integrating behavioral, leadership, and cultural and environmental changes. Such a model is typically used to explain an approach, program, and policy that will have an impact on greater acceptance and participation in conceptualizing an implementable and deliverable strategy. A comprehensive strategic framework should identify and develop agency-specific needs for creating and enhancing a mental health program.

All facets of the socio-ecological framework require simultaneous attention. They are symbiotically reliant on the growth of each other, such as governments’ or elected officials’ financial and policy support; governance, capability, and organizational relationship enhancement; social and cultural reform; enhanced leadership understanding and training; social connectedness strategies; and individual knowledge and literacy extension.

Conclusion

Recognizing, normalizing, and accepting that psychological injuries, just like physical injuries, form an integral and expected element of policing will go a long way in assisting and encouraging members to come forward should they sustain any form of psychological injury. Addressing police culture and leadership and embedding policy, structures, and processes into institutional foundations will help overcome existing major impediments to better mental health and well-being in agencies.

Inculcating mental health dialogue into policing throughout all facets of the policing ecosystem, terminology and jargon, leadership, training, and culture will have a positive effect in achieving structural trust and overcoming individual skepticism. Overtly introducing constructive changes within organizations will emphasize to staff that police leaders are serious and committed to ensuring the psychological health and well-being of their people and that it is of paramount importance.

By doing so, police departments will encounter greater productivity, lower levels of absenteeism, lower insurance premiums, reduced risk factors for diseases and illnesses, improved quality of life and sense of well-being, greater staff recruitment and retention, better cognitive performance, and reduced stress. Such an approach encourages and supports stronger employee-employer relationships and, most important, will save relationships and lives.

Notes:

1Anthony D. LaMontagne et al., “Workplace Mental Health: Developing an Integrated Intervention Approach,” BMC Psychiatry 14 (2014), article 131.

2Cheryl Regehr and Vicki R. LeBlanc, “PTSD, Acute Stress, Performance and Decision-Making in Emergency Service Workers,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 45, no. 2 (June 2017): 184–192.

3Jodie Hargreaves, Hannah Husband, and Chris Linehan, “Police Workforce, England and Wales, 31 March 2018,” Statistical Bulletin 11/18 (2018).

4Dane Subošić, Slaviša Krstić, and Ivana Luknar, “Police Subculture and Potential Stress Risks,” (paper, Security Concepts and Policies New Generation conference, Ohrid, MK, July 2018).

5John M. Grohol, “Symptoms & Treatments of Mental Disorders,” December 8, 2020; Laurie Anne Pearlman and James Caringi, “Living and working Self-Reflectively to Address Vicarious Trauma” in Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders: An Evidence-Based Guide, eds. C. A. Courtois and J. D. Ford (New York, NY: Guilford Publications, 2009), 202–224; Jim Foley and Kristina Louise Dawn Massey, “The ‘Cost’ Of Caring in Policing: From Burnout to PTSD in Police Officers in England and Wales,” The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles (May 2020): 1–18; The Senate, Education and Employment References Committee, The People behind 000: Mental Health of Our First Responders (Commonwealth of Australia, 2018).

6PolicePTSD.com, “Police Stressors,” 2011.

Please cite as

Grant Edwards, “The Divergence of Institution, Leadership & Culture: Creating a Better Health & Well-Being Environment in Policing,” Police Chief Online, May 5, 2021.