Policing is at a crossroads. With the advent of mobile cameras and social media, the police face unprecedented public scrutiny. How policing responds matters, not just for agencies and officers, but for communities too. If policing is to increase the respect in which it is held, it must recognize the importance of not just being ethical but of being seen to be ethical.

Why Is Policing Important?

The word “police” might encourage the view that a homogenous approach to law enforcement is taken across the globe. That would be wrong. Policing in totalitarian states is different than policing in democracies. Even within democracies, there is not always a single group of police. In the United States, many thousand different services exist, often with different values and leadership styles and, consequently, with different approaches to service delivery.

Policing is central to democracy and the settlement between individual, state, and police requires balance.1 For the police to serve as citizens in uniform, they must do so with the consent of the community beyond their own ranks and possess high ideals and an ability to inspire others.2 Consequently, the recruitment and retention of officers whose values match those of the particular agency and the community it serves is a key starting point in achieving a values-based service.

This is important because the significance of policing cannot be understated. In one sense, officers have more power than presidents as they can remove a person’s liberty. This places significant responsibility on officers in defining their relationship with communities. In some minds, an officer is the “best friend of… the people”; to others, they are a “tainted occupation… ambivalently feared.” Regardless, it is fair to say that modern policing is a multidimensional discipline in which officers serve “not mainly as crime fighters or law enforcers but rather as the providers of a range of services to members of the public, the variety of which beggars description” where officers have to find “unknown solutions to unknown problems.”3

It is submitted herein that it is clear and values-based leadership that ensures the police are able to face and solve unknown problems.

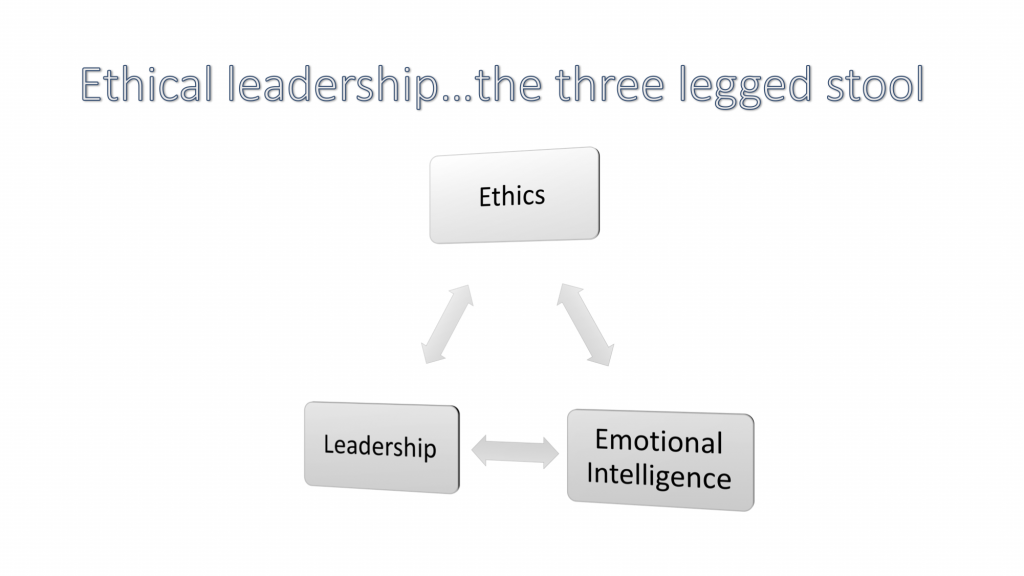

The Three-Legged Stool

A values-based approach to police leadership is based on three elements: leadership itself, emotional intelligence, and easily understood values. These elements form a three-legged stool upon which a leader can confidently sit. Should any leg come off; however, the seat loses stability and the leader risks falling off and landing in the mud. It is useful to briefly consider each leg and think about how to keep the stool secure.

Ethics and Policing

The word ethics derives from the Greek ethikos meaning “arising from custom.”4 Consequently, ethics should not be attributed to a particular set of values; rather, it should be used to describe habits.

The challenge for police agencies, as well as for their officers, is to think about their particular habits and consider whether they reflect the values of modern policing. It’s a useful challenge for any leader to actively consider what his or her values are. This is no easy task and demands reflection and honesty. Many people will, for example, say that they have integrity, yet when asked to describe that trait, they are not able to do so. If a leader can’t describe integrity to him- or herself, how can he or she describe it to teams and communities?

If a police service plans to tell its community of the agency’s values, the vast majority of that agency’s staff should not just be able to articulate the words but also be able to describe those values and their characteristics.

Once one’s values are understood, it is important to make these characteristics habits. It’s also important to note that individual values permeate one’s whole life; as one senior leader noted, “I don’t have professional values and personal values; I have got my values.”5

Understanding the values of a police service is essential to everyone with a stake in it. Officers must know what is expected from them, and communities must understand what to expect from the police. The importance of developing a code of ethics for policing cannot, then, be understated.

The work done in Scotland serves as a good example of how defining values and a code of ethics helped policing look at itself and, through a discussion with communities, better understand what community members wanted from a police service.6 An agency’s values should underpin policing and, where these are enshrined in a code of ethics, a “tangible basis for public trust” will develop.7

Once leaders understand their values, it is important to consider the second leg of the stool—emotional intelligence.

Emotional Intelligence

There is a high degree of emotional labor in policing, and officers “frequently experience stress at a higher rate than other careers”; for this reason, it is essential that leaders possess the necessary skills to support their staff.8 A strong use of emotional intelligence (EI) is a key component of this.

EI principles emerged in the mid-1960s, but it was Daniel Goleman’s book, Emotional Intelligence—Why It Matters More Than IQ that brought EI into the canon of leadership.9 Goleman divided EI into five elements:

-

- self-awareness

- self-regulation

- social skill

- empathy

- motivation

Understanding and being able to acknowledge one’s emotions at any given time and assess how these will affect others are key strengths of leadership.

Leaders, like all human beings, have competing pressures, including personal ones such as family and health. Emotionally intelligent leaders understand these pressures do not stay at home; they enter the office too. Emotionally intelligent leaders will, however, also know how to manage these pressures.

As leaders reflect on their values, it is worth taking time also to reflect on the EI and well-being of—both themselves and their officers. Asking these two questions could help.

-

- How do I know I’ve had a good day?

- How do I know my people have had a good day?

On first view, these appear simple; however, it is important to really reflect on them. Often respondents will say things like, “when I’ve answered all my emails” or “not got into trouble.” Are these really the types of things that underpin a good day? They might be elements, but the health of children, a happy marriage, or time spent with friends may well be more important.

Leaders can get sucked into their roles; it’s important to find time to reflect on how they feel and how their emotions affect others. By doing so, the second leg of the stool remains fixed.

Leadership

The third leg of the stool is, of course, leadership.

The Dutch for leader is leider, which translates into “show the way.” Consequently, one of the key questions leaders should be able to answer is “Which way are you showing?”

Followers want leaders to be role models; it is key that leaders understand the importance of ethics in all they do and are properly trained in this area of leadership.

Scottish police leaders benefit from such training throughout their career progression. This prompts reflection around moral responsibility and promotes a deeper understanding of the impact they, as leaders, have upon their followers, the wider police service, and communities.

Effective leaders will develop an exchange relationship with their team.10 Where trust and respect are high and mutual, both leaders and followers benefit, and leaders who demonstrate ethical behavior inspire trust among their staff.11 For trust to develop, it’s necessary for leaders to take responsibility for their values and actions. Where leaders demonstrate positive values, decisions are more easily discussed, debriefed, and learned from. Where this is evident, a department will evolve into a truly ethically based, learning-led organization.

A senior British military officer once said, “Moment by moment, within the intimacy of every interaction you are being judged by those around you.”12

Arguably, this assertion is as true today as it ever has been. The challenges for policing going forward will be to first understand that such judgments are being made and, then, effectively respond to them.

Leaders should have visions for themselves and their organizations. This concept should be more than a departmental poster. Developing a vision should see leaders authentically consider where they are taking their teams and how they plan to support their communities. Policing is at a crossroads with others looking in—particularly at how departments are led—and there has never been a more essential time to reflect on and share that vision.

A strong and communicated set of values, lived as habits and set into a vision for effective leadership, will support the development of leadership and community cohesion and keep the third leg on the stool.

National Decision Model (NDM)

Leaders will be continually asked to reach decisions. Like values, for decision-making to be effective, it must be consistent and demonstrable.

Police decision-making is complex because policing is a complex business.13 While a particular course of action may appear obvious either to the officer or community member, it might not be obvious to both. It is essential then that leaders are able to articulate decisions in an accessible way.

Judgement is a key tool for leadership. Many commentators note the necessary ability of officers to make good decisions and demonstrate sound judgement.14 However, situations do arise that are particularly challenging and engage the values of officers and their agencies. It is essential that officers possess values consistent with policing and demonstrate such to the public.

Consistency in decision-making is important for both the officers reaching judgments and the community members affected by those decisions. UK officers use the National Decision Model (NDM) to consider their response to operational situations.15 The model is easily navigated and understood. UK policing benefits from its being multijurisdictional; officers from all agencies apply the same methodology to decision-making. In turn, this gives members of the public consistency in their understanding of police decision-making.

The NDM is often described as the “crossing the road” model because all of the elements used in the NDM are used when people cross a road. We gather information—is the road busy? We assess threat—is it safe to cross? We consider our powers—do I have the strength to cross the road? We identify options—is this the best crossing point or should we use the overpass? We then take action and cross the road.

While this might appear trite, it does underpin the utility of the NDM and its ability to be applied in most operational situations.

With that in mind, it is worth considering the NDM in some more detail.

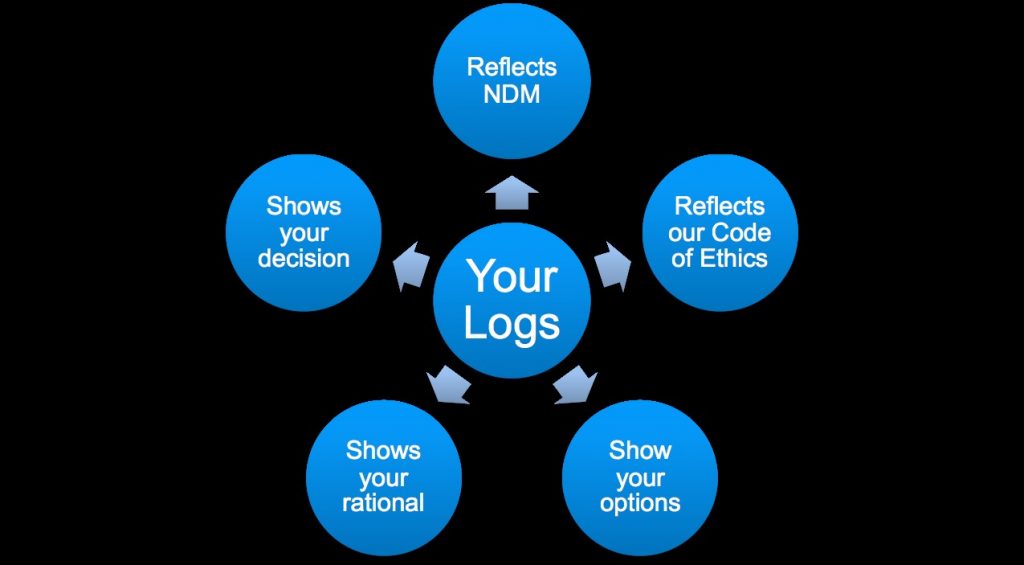

Code of Ethics

At the center of the NDM is ethics or values. As decision-makers draw their conclusions, they must confirm their thinking is ethically sound. This reduces the risk of acting unethically. However, should decision makers feel at any of the five stages in the model that their actions do not meet the ethical standards required, then, no matter how much they may hope to the contrary, the resulting action will never be ethical. Put simply, if any proposed action fails the test, that action should not be undertaken.

Gather Information and Intelligence

It’s incumbent on decision makers to establish both what they know about a given situation and what they don’t. This assessment will form the basis for action throughout and a well-articulated understanding of the situation and any gaps in knowledge that underpin the activity.

It is important that any assessment made and action taken reflect what was known at the time of that action. There is always a risk that those with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight will see events through a very different lens as they will, inevitably, know more than the officer who was faced with the situation.

For this reason, it’s essential that decision makers record what they’ve done and why at every step of the process. How that should be done is dependent on circumstances. The essential element is that logs are made. This protects the decision maker as it will be clear from these logs what the circumstances were and why, consequently, the decision was made. Ensuring scrutiny through this lens makes it easier to weather post-event critiques!

Assess the Threat

It is important the decision maker undertakes an analysis of the threat faced. A considered approach will be the basis for any response and give a rationale for action.

Decision makers should consider what they are seeking to achieve and “begin with the end in mind.”16 This may be the arrest of an offender or, equally, the safe passage of a protest. Threats may be physical and also reputational. Consequently, a clear understanding of any objective is essential at the outset.

An analysis of risk might also point to potential benefits, such as better community relationships or the reduction of tension at a protest.

Sometimes, this is challenging. Recently, UK protesters removed a statue dedicated to a slave trader.17 The police did not stop this action. In one view, this may be regarded as failure to maintain public order; in another, this might be regarded as excellent decision-making. A review of the statue’s appropriateness was already being undertaken; the local community did not want the statue or to be associated with what it represented. When the protest started, by not intervening, the police ensured no injury occurred to protestors, other members of the public, or officers—and the reputation of the relevant police service was arguably enhanced.

Given the resulting scrutiny, it was essential that the decision maker effectively logged and rationalized all decisions. In this instance, the police service received broad praise for what was, arguably, a brave approach to a challenging situation.18 The police decided not to intervene to stop disorder or arrest protestors while offenses were taking place. In the view of the officer in charge, this “would have caused more disorder and disruption during the protest.”19 This was not a view universally shared within policing. The chairman of the Police Federation criticized this decision on national news, taking the view, noting that to “not to have a police presence there was… a decision I have not seen taken before.”20 The existence of a strategy to maximize safety and minimize risk underpinned this “courageous decision in a very hot moment” and provided documented rationale for the officer in charge’s decision making.21

Setting out a working strategy helps to bring these elements together. Strategies should be simple documents, which set out the key elements the decision maker is seeking to achieve. For example, maximizing public safety and minimizing risk to officers, as in the preceding example, may well be elements of a working strategy. Once completed, strategies underpin all actions taken. In short, if an action does not reflect the strategy, then it should not be taken.

Consider Policy and Powers

Decision makers should understand the legal and procedural parameters they are working within. It should be assumed police officers know the law. This is an aspect of training, and it is the responsibility of chief officers to ensure this training is given to officers and reflects the challenges and decisions officers face.

Understanding and applying policy is important, too. It is incumbent upon agency leaders to ensure policy is up to date and cascaded down to and understood by officers. It is useful for police agencies to identify national policies that they may wish to adopt locally or found their policies on. Bodies such as IACP are useful starting points for this.

However established, it is essential that officers understand the authorized environment they operate in.

Examine Options and Contingencies

It is essential that decision makers are able to rationalize all potential activity before action is taken, the underpinning principle being that the action taken will result in the least harm. This may require balancing harm to individuals with harm to the reputation of policing. It is important that decision-making is contextualized within the time and resources available against the immediacy of any threat.

It is useful to consider and apply the PLANE Model. Decision makers should reflect on whether their proposals are

- Proportionate to the circumstances

- Legal

- Accountable to the wider community

- Necessary to achieve the strategy

- Ethical within Departmental values.22

Decision makers should consider all potential options open to them, record these options, and select the favored response.

Take Action and Review

Once the favored option has been selected, then action should be taken. It is useful at this stage for decision makers to reflect and consider who else they may need to inform. Who might ask, “Why was I not told?”

Reviewing the incident and learning from it sit at the heart of a learning-led approach to policing. There is usually something, no matter how small, that might be helpful to others faced with similar challenges. Opportunities should be put in place for learning to be shared. This might be within a particular agency; it might also be at the national or international level. Leaders have a responsibility to ensure mechanisms are in place for learning to be shared. This can often be the difference between lessons being merely identified and lessons being learned.

Conclusion

Effective leadership is established and maintained through regular self-reflection, consistency, and clarity. The use of the three-legged leadership stool in conjunction with the NDM offers all these elements both to followers and communities. 🛡

Notes:

1 Michael A. Caldero and John P. Crank, Police Ethics: The Corruption of Noble Cause, 3rd ed. (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2015).

2 Charles Reith, A New Study of Police History (London, UK: Oliver and Boyd, 1956); John S. Dempsey and Linda S. Forst, An Introduction to Policing, 5th ed. (Clifton Park, NY: Delmar, 2010).

3 Robert Reiner, The Politics of the Police, 4th ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010).

4 P.H. Nowell-Smith, Ethics (Middlesex, UK: Penguin, 1954).

5 Richard F. Adams, Does the Police Service Require a Values-Based Decision-Making Model? If So, What Should That Model Look Like? (doctoral diss., London Metropolitan University, 2014).

6 Police Scotland, “Code of Ethics for Policing in Scotland.”

7 John Kleinig, The Ethics of Policing (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

8 Michael McCutcheon, “Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Stress of Police Officers,” InSight 14, no. 1 (Fall 2018).

9 Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (London, UK: Bloomsbury, 1996).

10 Rubina Mahsud, Gary Yuki, and Greg Prussia, “Leader Empathy, Ethical Leadership, and Relations-Oriented Behaviors as Antecedents of Leader-Member Exchange Quality,” Journal of Managerial Psychology 25, no. 6 (2010): 561–577.

11 Paul Gregory, “Ethical Leadership,” Training Journal (September 2010): 44–47.

12 C. Keeble, Ethical Right to Lead (SLDP Scottish Police College, Manchester College, Oxford, 2009).

13 Peter Neyroud and Alan Beckley, Policing, Ethics and Human Rights (Cullompton, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2001).

14 Herman Goldstein, Problem-Oriented Policing (New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 1990); Neyroud and Beckley, Policing, Ethics and Human Rights; Reiner, The Politics of the Police.

15 College of Policing, “National Decision Model,” 2014.

16 Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (New York, Simon & Schuster, 2004).

17 Tom Wall, “The Day Bristol Dumped Its Hated Slave Trader in the Docks and a Nation Began to Search Its Soul,” The Guardian, June 14, 2020.

18 “Black Lives Matter: Bristol’s Colston Protest Police ‘Didn’t Lack Courage,’” BBC, June 10, 2020.

19 Jasper King, “Police Explain Why They Didn’t Stop Protesters Toppling Edward Colston Statue,” Bristol Live, June 8, 2020.

20 Jess Flaherty and Jasper King, “Police Federation Condemn Bristol Police for Not Intervening over Edward Colston Statue,” Bristol Live, June 8, 2020.

21 “Black Lives Matter: Bristol’s Colston Protest Police ‘Didn’t Lack Courage.’”

22 A.A.R. Freeburn, Building Blocks for Ethically Empowered Judgments: A Framework to Support the Decision-Making Model for Policing (Belfast, UK: Association of Chief Police Officers, 2009).

Please cite as

Richie Adams, “Values-Based Police Leadership,” Reimagining Policing & Community-Police Engagement Series, Police Chief Online, July 29, 2020.